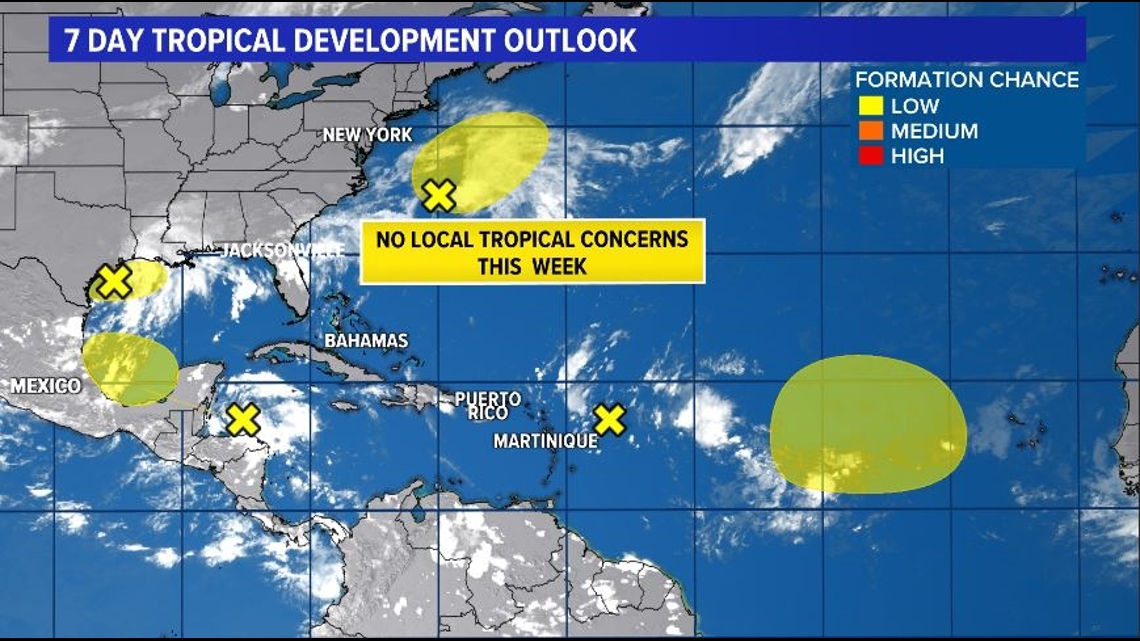

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Despite the National Hurricane Center monitoring five separate areas for tropical formation over the next seven days, none of them have a very high chance of development. They actually all have a low chance of formation, which has been the trend in the tropics since we saw Hurricane Debby in early August.

Since Debby made landfall in Florida, the tropics have remained fairly quiet. We have monitored tropical waves moving off the coast of West Africa and even a few that have moved into the Caribbean, but no tropical cyclones have formed.

NOAA’s 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook forecasted above average activity with potentially 17-25 named storms. We have now reached the climatological peak of hurricane season and have only seen five named storms develop.

So what’s going on?

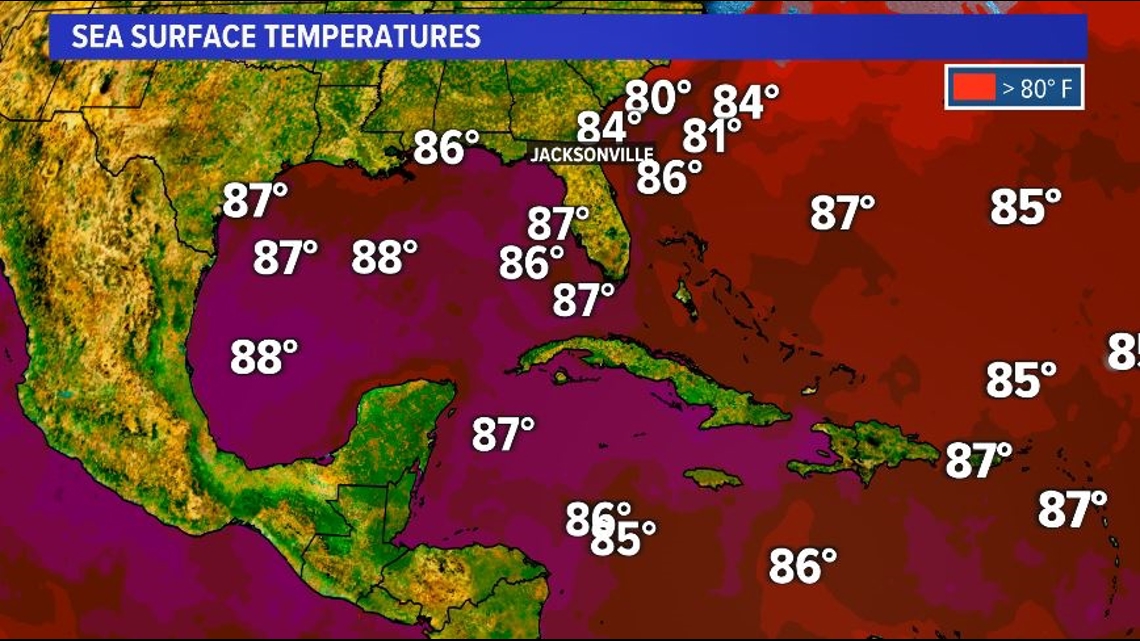

Sea surface temperatures and ocean heat content across the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico are incredibly high, so conditions at the surface are ripe for a storm to develop. But why aren’t any of these tropical waves developing into tropical cyclones?

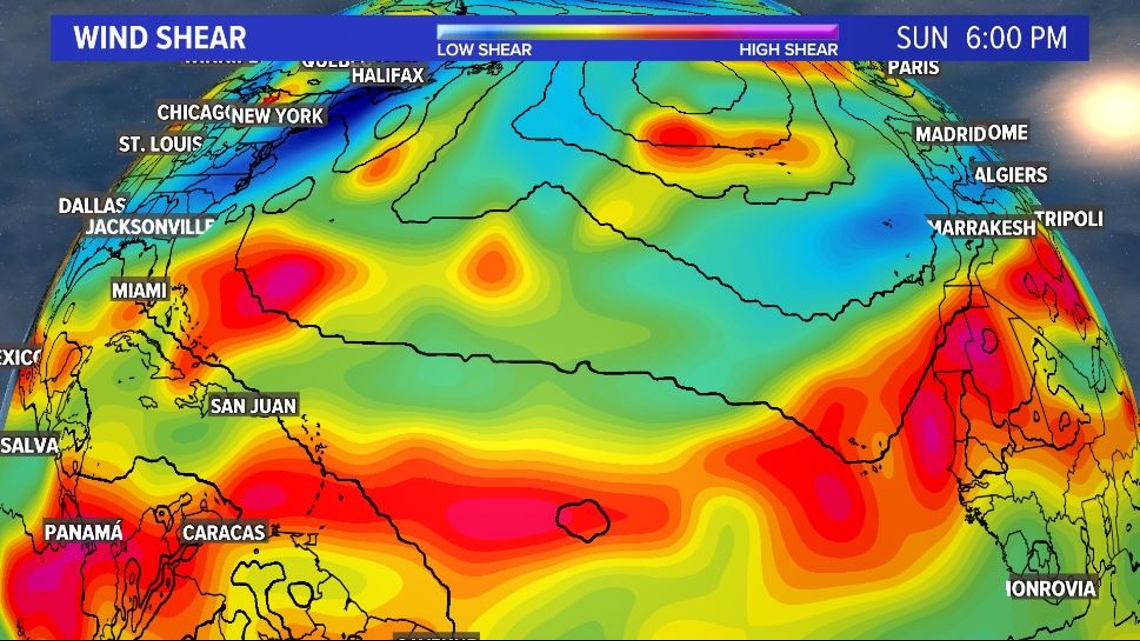

A multitude of factors have diminished the activity and intensity in the tropics over the last three to four weeks, particularly conditions aloft in the atmosphere.

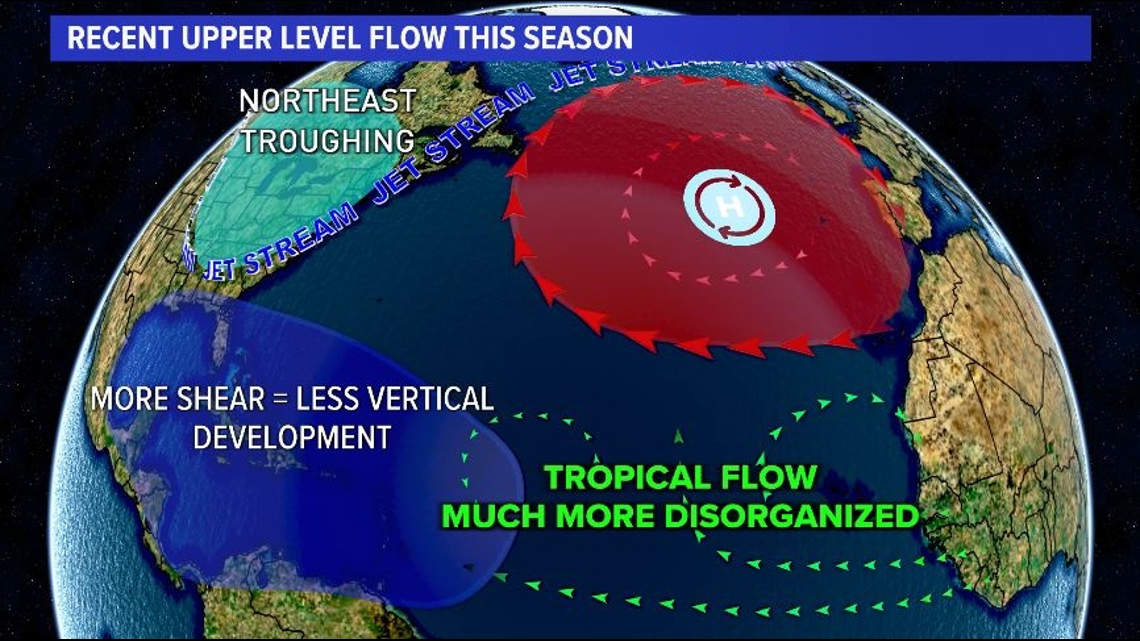

La Nina typically leads to less vertical wind shear in the tropics; however, La Nina has been coming on much slower than previously expected, allowing for the wind shear to remain high.

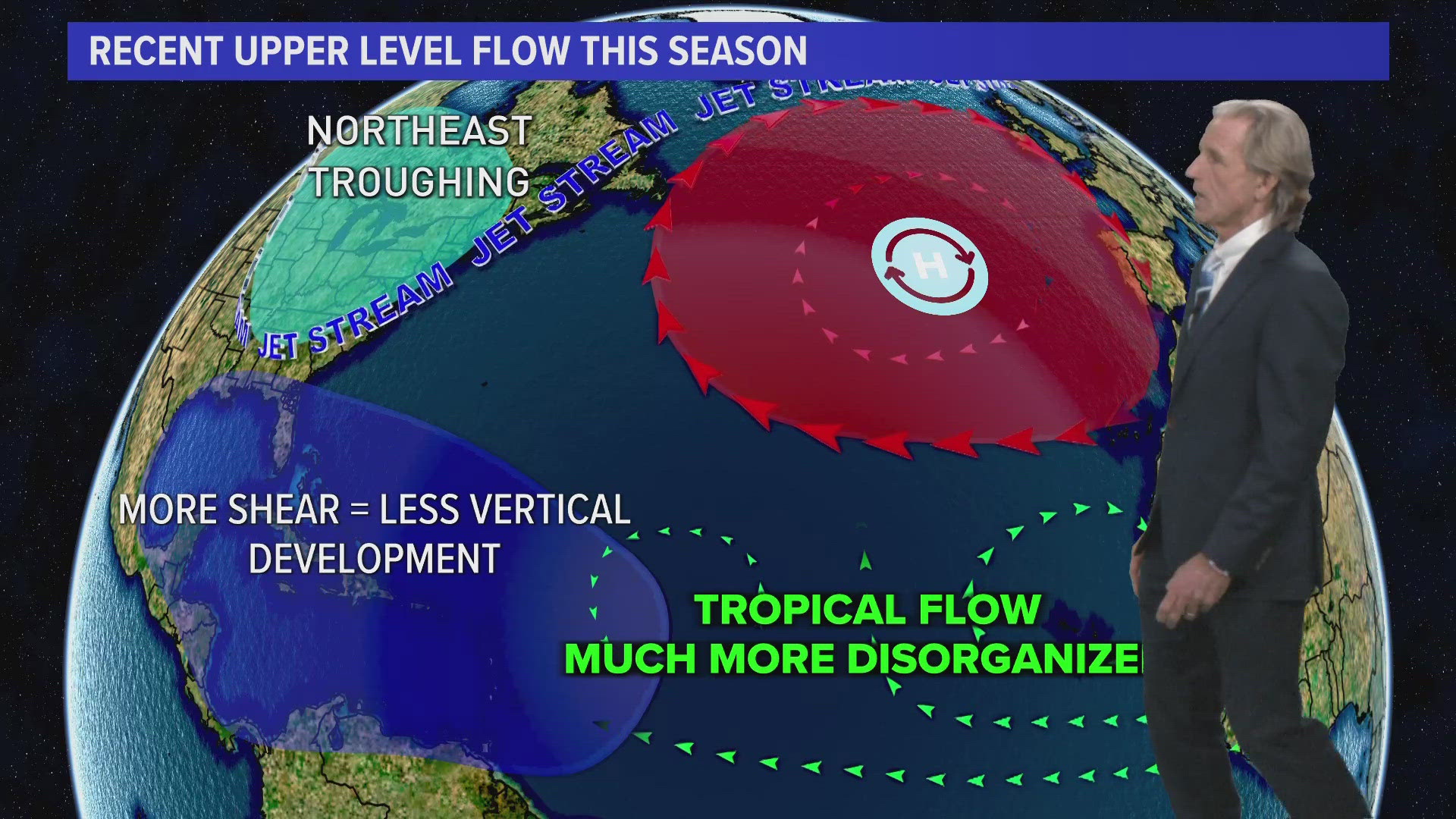

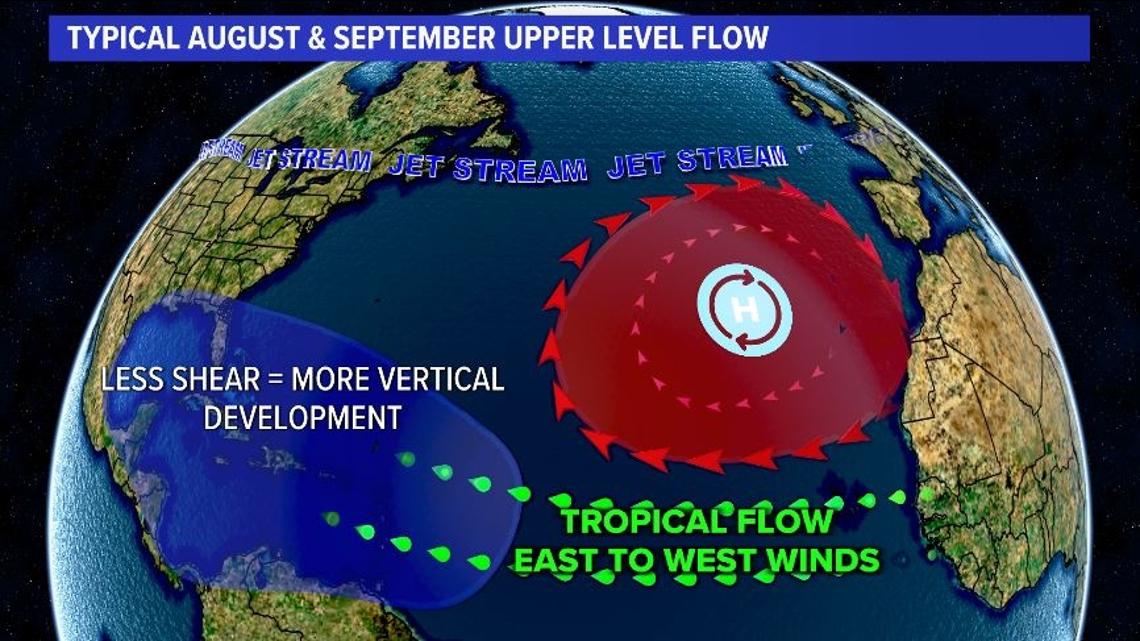

For most Augusts and Septembers, the jet stream remains fairly zonal across the United States and Atlantic Ocean, allowing for the tropical ridge of high pressure to sit farther south, and therefore allows for a tropical steering flow from east to west from Africa toward the Caribbean.

In contrast, the past few weeks have seen large dips in the jet stream across the Midwest and Northeast, leading to a large arc in the jet stream across the northern Atlantic toward Iceland and Greenland. When this occurs, the tropical ridge of high pressure slides farther north and creates this void of circulating eddies with no real dominant flow pattern beneath it to the south – an area where tropical cyclones will often form this time of year.

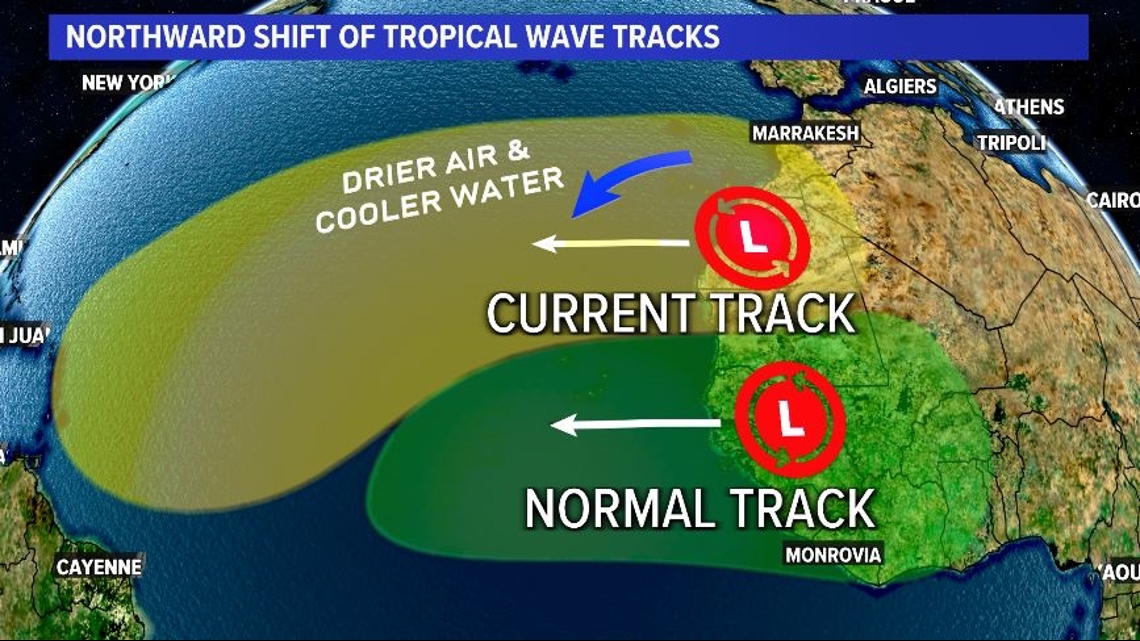

It is normal for tropical waves to roll off the African coast south of the Cabo Verde Islands this time of the year where there are warm ocean waters and plenty of moisture. Recently, however, cooler waters near the equator have pushed the warmer waters and tropical wave train farther north. In doing so, tropical waves have not only been emerging from Africa over much cooler waters, but they’ve also become engrossed in Saharan Dust. Both the cooler waters and drier air inhibit tropical development.

How long will these unfavorable conditions last? About another week. A more typical tropical pattern appears to return by mid-to-late September.