JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Snow - some of us love it and some of us would be happy if we never had to hear of it again. But whether you like it or not, snow is an important part of our Earth's climate.

For starters, snow helps keep our planet cool and makes up more than 50-percent of the Western U.S. water supply, which underpins local economies and cultures from coast to coast.

So, how is climate change affecting snow?

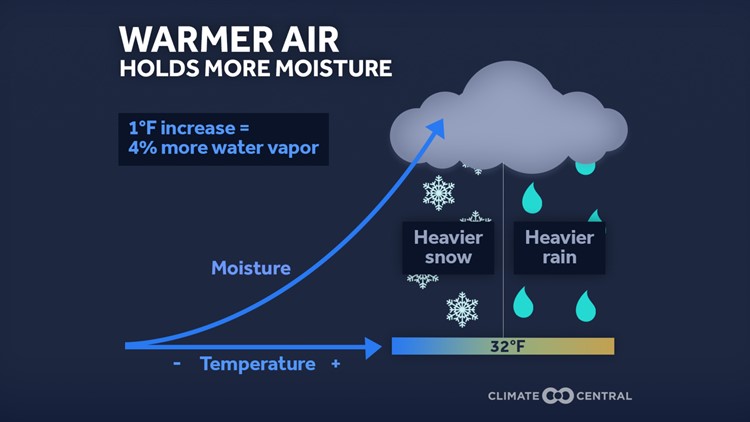

Let's start with the basics of what ingredients are needed to produce snow. Simply put, you need freezing temperatures alongside enough atmospheric moisture. However, both of these conditions are being affected by the changing climate.

One thing we're noticing this winter across Jacksonville, for example, are fewer freezes. As of January 20, we've only recorded two freezes at the Jacksonville International Airport. The "normal" would be to have at least ten freezes by this point in the season.

Did you know winter is the fastest warming season for most of the U.S. and the numbers of days with temperatures below 32F is expected to decline in the coming decades.

Another factor needed for snow - moisture. Our warming atmosphere holds about 4-percent more moisture per every 1F of temperature rise. Even with more moisture in our atmosphere, there's no guarantee it'll fall as snow where it normally would.

According to a Climate Central analysis of snowfall data from 1970–2019, Fall snowfall (before December 1) decreased in every region of the country with available data. Spring snowfall (after March 1) decreased in all regions except for the Northeast and the East North Central regions. And, Winter showed a mixed record, with increased snow in North Central regions, and decreasing snow in southern regions.

Climate change can affect the timing, location, and amount of snowfall, as well as the dynamics of snowmelt. But these changes—and their wide-ranging impacts—vary among regions.

For instance, across the the mountainous Western U.S. has experienced declining snowpack, earlier snowmelt and streamflow, and a shift toward less precipitation falling as snow. A 2018 study shows that decades of shrinking snowpack has reduced snow-derived freshwater in the West by 15-30% since 1955.

In the Northeast, there has been an increase in the proportion of winter precipitation falling as rain rather than snow. This trend is projected to continue over the 21st century with a northward shift in the snow-rain transition zone.

Across the Great Lakes Region, despite year-to-year variability, long-term trends show an average 22% decline in annual maximum ice cover across all of the Great Lakes since 1973.

Finally, in the Northern Great Plains, the warmer climate has led to shorter snow seasons and a decline in snowpack water storage. Mountainous areas of the Northern Great Plains also face snow-dependent economic and ecological risks due to climate change, including shorter skiing and snowmobiling seasons and fewer visitors.