JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — It’s hard to think of Dinsmore as ground zero for sea level rise in Jacksonville.

Northwest of the beltway and about halfway to Callahan, the area is a good 45 minutes from the closest beach.

But it’s just one of several inland communities at most risk from rising seas.

A vulnerability map by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also identifies Orange Park, Southpoint, Englewood and Springfield as among the most vulnerable, along with most of Northwest Jacksonville and all the urban core.

It’s a fact that will become more evident as seas creep up anywhere from a half-inch to nearly 2-inches a year. (That that does not factor in rapid melt recently discovered in the so-called “Doomsday glacier.”)

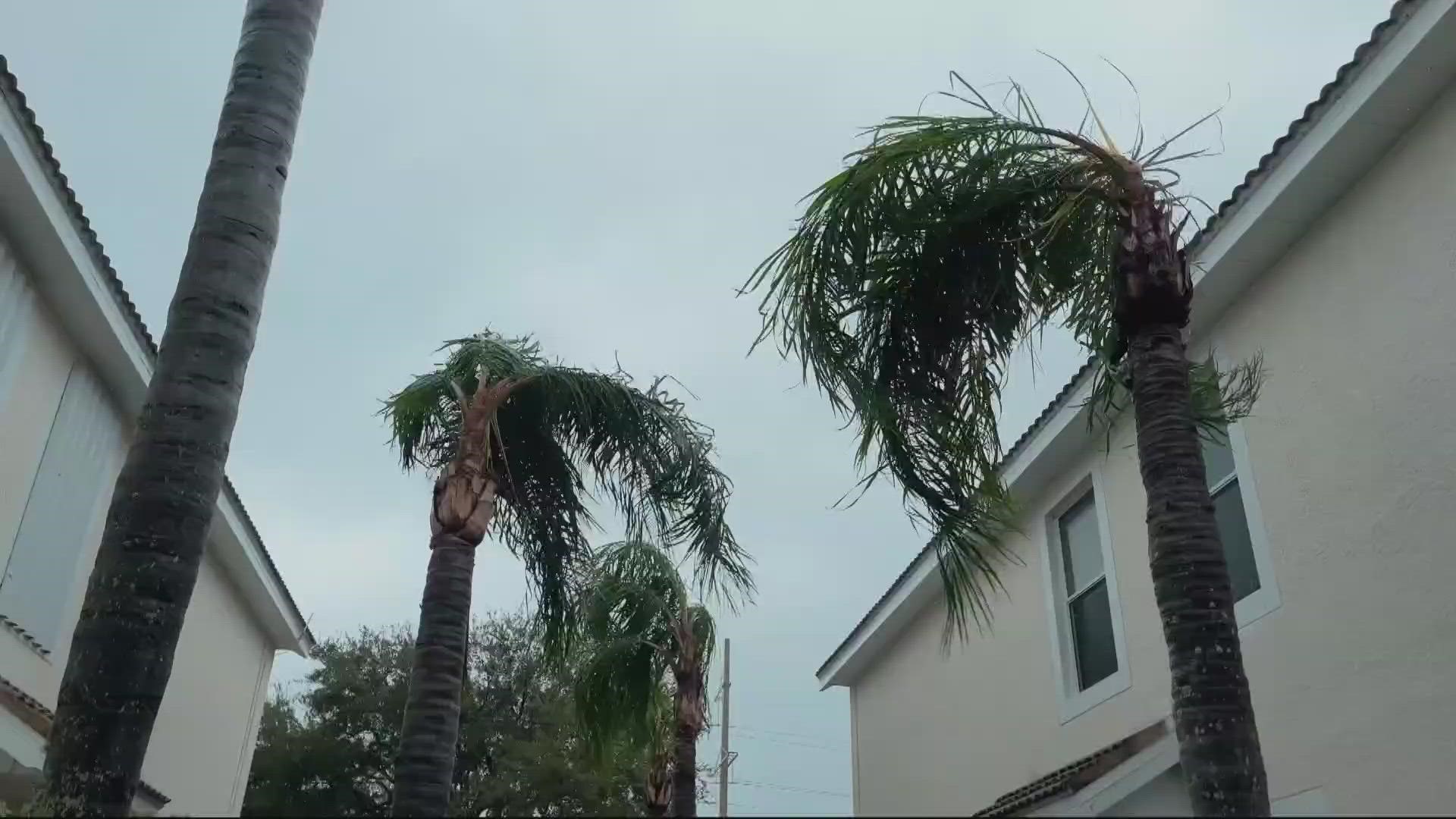

“Flooding is happening in pretty much every corner of Jacksonville,” says Anne Coglianese, Jacksonville’s first-ever chief resilience officer. In part, that’s because the city’s vast network of tributaries reaches deep inland. It’s also because climate change increases the risk of compound flooding, which occurs when different kinds of flood hazards occur simultaneously, including heavier rainfall, higher river levels, more powerful tropical storms and extreme high tides.

“We're anticipating a major increase in the number of extreme high tide days that we experience,” Coglianese says. “Right now, it's roughly 4 every year. And we have projections that look at sea level rise that are saying it could get up to 40 to 60 days a year.”

An extreme high tide, Coglianese says, looks a lot like “what we've seen in downtown with tropical storm Nicole and Ian, but seeing that without a major storm event. It would just be the static rise and fall of the tides that could do that.”

Coglianese has spent much of the past year and a half amassing data on Jacksonville’s vulnerability to a range of risks associated with climate change, including the deadliest of all weather events: Extreme heat. Recent flood events have made city residents particularly percipient of water hazards, but the NOAA vulnerability map would no doubt surprise many inland residents.

“There are areas of the city that are set back from kind of the main waterfront of the main channel of the St. Johns River, but could be at a really substantial risk for flooding,” she says.

“They're more at risk to flooding than some areas that are close to the coast,” agrees Brendan Rivers. For the past four years, Rivers has managed ADAPT, a digital magazine and podcast focused created by Jax Today on climate change in Northeast Florida.

His work has focused on a variety of climate change impacts, but says as in other Florida cities, what is arguably Jacksonville’s greatest asset is also its greatest threat.

“People want to come to the state because of the water. So they want to be near the water, they want to be on the water,” Rivers says. “But the truth of the matter is: That's not a safe place to live.”

Preparing for that reality is going to require both major investments in infrastructure and a radical revisioning of how the city does business. Public works projects will need to be modified to withstand rising waters (some city bulkheads are already being designed to allow for a second, higher level of protection to be added later). Homes will need to be elevated, but so will sewage and pump systems. Septic system failures could become endemic, particularly along the coast.

The road network is also in serious peril. A new flood risk assessment map assembled as part of the city’s resiliency planning shows many roads in red: Impassible.

“Sections of the city are cut off,” Coglianese explains. “So suddenly, the red on our map is looking at where residents can't get in and out of their neighborhood. Their home might be fine -- high and dry and completely safe -- but their life is nonetheless impacted.”

The flood assessment can be daunting, but Coglianese says it’s important to remember that water – despite its risks – also makes Jacksonville a desirable place to live. “We need to see the river as both a real tangible threat but also such an opportunity. That's the reason people like living in Jacksonville. And we don't want people to be scared of the water, we just need to make sure that we're planning for it as a city.”

That planning process will cost millions, take years and in the end, may not prevent the flip side of resiliency: Retreat. But despite the monumental challenge, Coglianese says the city is engaged and prepared to confront its turbulent future.

“I feel very optimistic, because I think what we have the ability to do now is to see the worst case scenario and get in front of it.”