Two were only 13 years old. Three were just a few months shy of turning 18. Four committed their crimes in this decade, and just as many have spent more than 30 years behind bars. At least two sold sex for money. One witnessed his father being shot. Another was given beer for the first time when he was 4 years old. All but four had been arrested before. For most, they'd lost count of exactly how many times. These Florida inmates and dozens more have much in common: They played a part in ending someone's life; their crimes were committed in Duval County; and those crimes happened when they were still children.

All in prison for years, if not decades. All for killings that happened in Duval County when they were still kids.

It's a problem with a high cost. Taxpayers spend more than $2.3 million a year to house, feed and care for them. Communities lose even more.

There was Jose Lau, a Chinese immigrant who was delivering food on the Westside when he was fatally shot. Grady Williamson was stabbed in the chest for the $3 he had on him. Timothy Robertson gave a light to a stranger and ended up dead. Michael Demps was taking a walk while on break from college when he was shot dead. And there was De'Juan Graham, gunned down after a basketball game at a city park. De'Juan was 15.

Duval County, known for years as Florida’s murder capital, also leads the state in kids who kill.

In the last decade, 73 Duval County children have been arrested in cases of murder and manslaughter. Only one other county has more: Miami-Dade, which has nearly three times the youth population. Taking into account population differences, no other large county in Florida has a higher rate of minors arrested on these charges than Duval.

Last year here, four teenagers were arrested and charged as adults with second-degree murder. Two more kids — ages 11 and 14 — were charged in juvenile court with manslaughter, each in connection with the shooting deaths of other children. So far in 2018, two more teens have been charged in homicides.

Why is this happening? What leads kids and teens to kill? And what, if anything, can be done about it?

To learn more, the Times-Union spent more than 20 months examining juvenile homicide in Jacksonville. A major component of the reporting: listening to the people who committed the crimes.

The newspaper wrote letters to 103 of these inmates from Duval County. Fifty-seven wrote back. Of those, 25 answered an extensive survey about their lives developed by the newspaper in consultation with experts in mental health and criminal justice.

What these inmates reveal in hundreds of handwritten pages is wrenching in its repetition: Their fathers were absent. Their mothers and caregivers did the best they could, but struggled. They fell in with the wrong crowd. They slid into crime. They needed help they never received.

“The reason so many kids commit murder in Jacksonville is not because they are murderers, but because they are everything else: drug dealers, robbers, thieves, rapists and a bunch of other types of criminals whose crimes of choice has a great likelihood of leading to a murder." That's Aaron Wright. He’s serving a 35-year-sentence for second-degree murder after one of his teenage co-defendants shot and killed a woman they’d set out to rob.

Why are so many Jacksonville children involved in serious crimes and at such a young age?

The Times-Union's research revealed four overarching contributing factors that are well known. What the newspaper's research showed with stark clarity was the number of children who face many or all of these challenges:

1. Trauma. Most of the Duval County kids who end up convicted in a slaying have a history of distressing events happening around them and to them. It's typically not just one or two bad things; trauma is often a constant companion in their homes, neighborhoods and schools.

2. Family dysfunction. The strain in families is often generational. Parents who were never parented appropriately will struggle to appropriately discipline and set expectations for their children. Eighty-four percent of survey respondents had divorced or separated parents, and just as many lived with someone who abused drugs or alcohol. More than half said they felt unloved or unimportant at home.

3. Violent environment. Violence is nothing new to most of the teens who end up in prison for killing. Eighty-four percent said they've been shot at and 72 percent had witnessed someone get shot. More than a third said a close family member had been murdered.

4. Dangerous peer influences. When kids commit crimes, they're more likely to do so with a friend or in a group. That's true for 84 percent of the kids who took the Times-Union's survey. Devoid of good role models and constructive things to do, teens will follow the stronger influence, not necessarily the positive one.

When these stressful and traumatic things happen early in life, they're called adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs. Study after study have linked having more ACEs to a variety of worse outcomes in a person's life, including illness, substance abuse, behavioral problems, criminality and even early death.

What are these adverse childhood experiences? They are: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, exposure to domestic violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, and incarceration of a family member.

In the original landmark ACE study of more than 17,000 people in the 1990s, 62 percent of people reported no or only one ACE. Only 12.5 percent of participants had four or more of the 10 ACEs.

Among the inmates who participated in the Times-Union's survey, the average number of ACEs was more than 5; and 18 of the 25 men and women had 4 or more.

Many of those inmates contacted by the Times-Union expressed doubts that they had anything worthwhile to say, because, they asked, aren’t their stories all alike? Weren’t their experiences typical? How would that actually help anyone? No one had wanted to understand them before, some said.

"All the other prisoners you are writing to may have the same story as I do," wrote Keith Shawn Hanks. He's serving a life sentence for a murder committed at age 17, back in 1992. "So, do you really want to do a story on me?"

To them, their highly abnormal experiences were normal.

"We should be heartbroken," said Carly Dierkhising, an assistant professor in the school of criminal justice at California State University, Los Angeles. "It is profoundly sad, and it also says a lot about our society and how we treat our youth."

Jason Cooper put it another way.

"In the community of Jacksonville, kids (are) growing up thinking it's all about street credibility, and (that) silly image along with gun play are mandatory in that life,” wrote Cooper, who was 17 when he shot and killed Wilson Sakudya in an Arlington apartment in 2007.

“If nothing happens to grab hold of that mindset, what you see now will always continue to be the same."

"I'm not some monster who go around wanting to take people (sic) life for nothing,” wrote Bobby Ray Johnson. He and his co-defendant, Kyle Gerard Joyner, were both 17 when authorities said Joyner shot and killed 30-year-old Gerale Ealey in 2003.

The kids who commit these types of crimes are not monsters, psychopaths or super-predators with a predisposition to kill, said Kathleen Heide, professor of criminology at the University of South Florida in Tampa. Heide has been evaluating and researching juvenile homicide offenders for more than 30 years, and is the author of “Young Killers: The Challenge of Juvenile Homicide.”

They’re not even inherently bad kids, she said. What these teens are, she said, are kids who have grown up with a lot of bad things happening to them.

“People sometimes miss that, or want to judge them,” she said. “They’ve grown up in very adverse conditions and when that happens, it increases the likelihood of bad outcomes.”

Of the 25 inmates who took the Times-Union’s survey, 24 reported at least one of the 10 adverse childhood experiences. But, there are other traumatic childhood experiences that are not captured in the 10-question ACE assessment, like the death of a caregiver, homelessness, and exposure to gun violence.

By that measure, all of the 25 participants endured multiple traumas as children.

On top of that, all of Duval County has a federally designated shortage of mental health care providers for its poorest residents.

That means for many kids, the exposure to all those bad things goes completely unmitigated. The level of violence they see even becomes normal. And their bodies and brains respond to that.

Repeated trauma doesn’t just mean a kid has a tough life, said Dr. Mikah Owen, a pediatrician who works with justice-involved and foster care youth in Jacksonville. It can actually change a child’s brain and the way they react to the world around them. They may begin to interpret things around them differently, perceive things as threatening when they are not, and disassociate from their surroundings.

“If a 16- or 17-year-old shoots somebody,” Owen said, “very rarely does that come out of nowhere.”

"The culture for the young there is so geared towards violence and some kinda gangsterish lifestyle that every young dummy with a gun and without a father worth a damn wants to be the next Tony Montana,” wrote 36-year-old Elijah Crady.

Crady said that’s his story. He was 16 in 1998, when he and three older co-defendants took part in the robbery and murder of 53-year-old David Drury. Police said Drury was shot dead while trying to flee the home invasion robbery at a friend's home; Crady and two others were sentenced for murder and the fourth co-defendant was charged as an accessory and pleaded no contest. Crady is serving a 30-year sentence for his part.

Crady described his home as broken, with no father around consistently and his mother’s various boyfriends as being problematic. He said they beat him and that he hated them for it.

“I’m ashamed to say there were times when I hated my mom, too, because of him,” Crady wrote of one of the boyfriends. “It seemed that she’d chosen him over me and didn’t want me around.”

Dierkhising, the professor in Los Angeles, said trauma and development are intimately linked, and that early in life that trauma often comes at the hands of a caregiver.

“The impact of that is much more profound,” she said. “That is the one [person] who is supposed to be keeping them safe and the one they want to run to when they’re unsafe, and that person is the one who is making them unsafe, or hurting them.”

That kind of experience can make kids hostile later in life and show them that being hurt is what relationships are about. When that behavior is learned and not corrected, the problem becomes inter-generational.

Just over half of the survey respondents, including Crady, said they were often physically hurt by a parent or another adult living in the household. Sixty percent said they were emotionally abused in their home.

“I’d rebel just to repay the hurt I felt,” Crady said. “I was not understood in that household, or wanted.”

Most of the letter-writers acknowledged their home lives weren’t ideal, but were careful to avoid blaming their mothers and grandmothers. The women in their lives, they said, did the best they could. Absent fathers, however, were not spared.

“I believe that my life may have took a different turn had my mother not had to move us in the projects, had my father been a man and raised me,” Tony Marvin Brown wrote. Brown, now 61, was 16 when he took part in a murder of a Springfield pharmacy clerk that earned him a 15-year sentence. He's back in prison on other charges now. “Because left to my own, the environment swallowed me up.”

Todd Thornton doesn’t understand why he had to grow up the way he did, but he’s accepted that he was “one of those kids from the streets of poverty.”

Thornton was 15 when he took part in a 2005 murder with two other teens — Corey J. Odol, 15, and Samuel D. Jones, 13 — and 32-year-old Henry Carlton Myers, who’d ultimately be convicted of three slayings. Authorities said Myers directed the teens to bound, gag, beat and stab 30-year-old Chad Edward Sullivan before setting him on fire. When Thornton reflected on his teen years, he believes he ran toward street life because of the hurt inside him and the hate around him.

“I was only 13 turf-warring about streets I didn’t even stay on,” he wrote to the Times-Union. “I was willing to give my life because I was telling myself it was right. Product of the environment. To be honest, we didn’t even care about dying because we knew we might not make it.”

Among the inmates surveyed by the Times-Union, gun violence was a constant. Most had seen someone get shot, and even more had been shot at themselves. Guns, they said, were not hard to find in Jacksonville. When everyone around them has a weapon, who wants to be the only kid without one?

Duval County Public Schools have far more violent incidents on campuses — more than 10,000 fights and physical attacks in 2016-17 alone — than Florida’s other large, urban districts. Duval reported 6,117 physical attacks and 4,315 fights that year. No other county came close to matching those numbers. Hillsborough County, which had the most incidents after Duval, had 4,433 attacks and fights.

These kids are also growing up in a city with a long-standing violent crime problem, especially when it comes to murder. With about 12 murders per 100,000 people in Duval County, and the largest share of those concentrated the city’s urban core, kids in some parts of town are exposed to violence early and often.

Kids who live in the urban core are more often shot than kids elsewhere in the county. Kids in Duval County are more likely to die by homicide than kids in any other urban area in Florida. The largest share of both groups: black boys.

“Everybody knows there’s no justice for young, black African Americans. There’s no second chances,” Thornton wrote before he was released from prison in July. “But that’s not what hurt(s) the most. I tell you, it hurts ‘til this day to do 15 years of my life without any support from the environment that I grew up in.”

Richard Leroy Douglas has a nickname for his city: Jack-N-Kill.

"I looked up to the older dudes in my neighborhood who sold drugs because I wanted to ride in the 'candy painted' cars with all the loud music and big rims,” Douglas, now 27, wrote. “Even though my mom, sister, granny and aunts drilled it inside my head that what I thought was cool was wrong and don't last long.”

As a pre-teen, Douglas said, he began to steal after he said his friends showed him how. At 9, he said he was arrested for stealing a BB gun from a store on Beach Boulevard.

His crimes escalated from there, he said.

“After seeing my family struggle working a 9-to-5, then seeing all the drug dealers buying what they want when they wanted it, I figured the street life had to be better than what my family was telling me,” he said, “which was going to school, and getting a good job when I'm old enough."

Douglas was 16 when he and three friends, all 17, set out to rob a Hendricks Avenue convenience store. In the pursuit that followed, police shot and killed 17-year-old Kenneth Marion Jr.

Douglas and his two co-defendants were charged with murder for Marion's death because of Florida's felony murder law. All three pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and armed robbery. Douglas is currently serving a 15-year sentence. His anticipated release date is 2023.

Douglas, like most of the young offenders who corresponded with the Times-Union, was with friends when he committed the crimes with which he was charged. It’s not uncommon to have three or four co-defendants in a single murder case.

Among the 25 inmates who completed the Times-Union's survey — which Douglas did not participate in — only four said they committed their crimes alone.

Of those with co-defendants, most didn’t set out to kill anyone; they’d planned to rob someone, break into a house or steal some drugs.

As anyone who is a teenager, spends time around teenagers or has been a teenager can vouch: friends, and what they think, matter a great deal to adolescents.

The influence of peers is so widely understood to affect a teen’s behavior — including criminal behavior — that the Supreme Court has recognized it as a factor deserving of consideration when sentencing youth.

Mandatory life without parole “neglects the circumstances of the homicide offense, including the extent of his participation in the conduct and the way familial and peer pressures may have affected him,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote in the court’s opinion in Miller vs. Alabama, a landmark case that struck down mandatory life without parole for juvenile homicide offenders.

Dierkhising said in moments when the pressure is on and peers are around, that’s when teens make especially impulsive decisions.

“It’s happening really fast,” she said, “and it’s not allowing them that time to process.”

In part, Jacksonville has a youth homicide problem because it has a bigger crime problem.

As Heide, the USF professor, pointed out: “Murder is often the byproduct of another crime gone wrong.”

According to a state assessment given to kids arrested in killings, Duval County children say they are more likely to commit crimes out of impulse — 53 percent in Duval County, compared to 38 percent statewide — than they are out of anger — 9 percent in Duval, versus 16 percent statewide.

In the Times-Union’s survey, 13 out of 22 respondents — 59 percent — said the slaying in which they were involved was the result of a street beef or another crime gone wrong. Of those who answered that way, nine of those crimes were intended to be theft, robbery or burglary, according to their own admissions and court records.

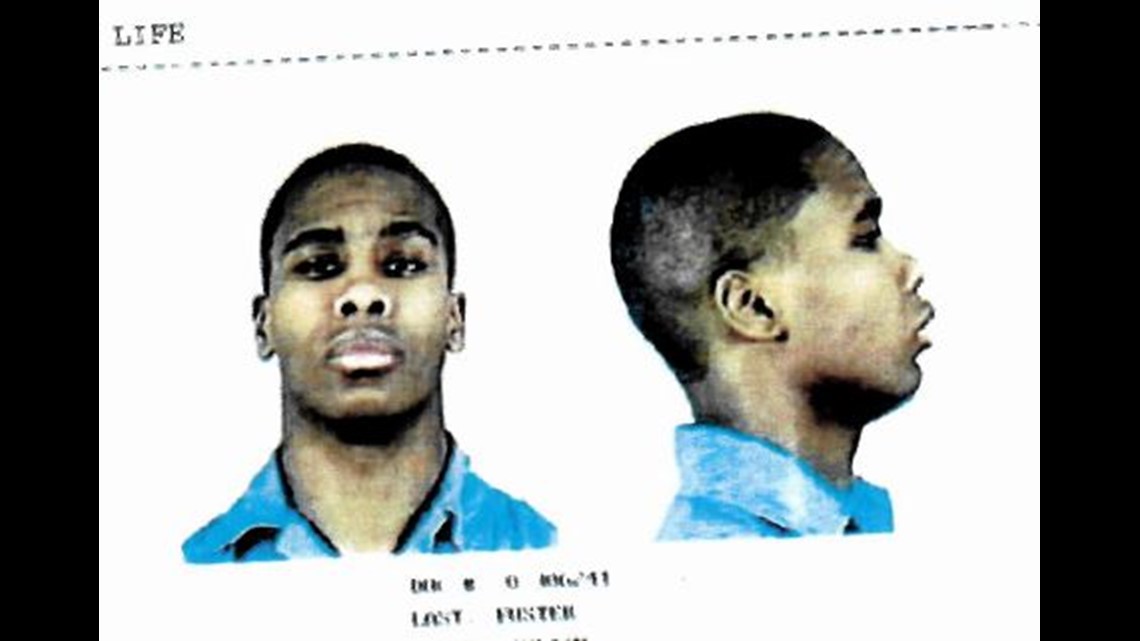

“It was an armed robbery attempt gone bad,” wrote Julian Foster, “and I wish I’d never done it.”

Many of these kids have few constructive activities, are followers by nature and, because they typically don’t set out to hurt anyone, Heide said, they don’t think through all the risks associated with their crimes.

“They’re chronically bored,” Heide said. “They’re doing substances, alcohol, drugs, and they’re looking for something to do. Someone says, ‘Let’s go rob somebody,’ and it sounds like a good idea.”

Foster said in 1994, he and some friends “were smoking weed and looking to get into something.” He was 17 then.

“We tried to rob a gentleman, who (then) shot and killed one of my co-defendants,” he said. The man they'd tried to rob outside a Days Inn on Lane Avenue shot Javan Holmes three times, killing him. “I was charged with my co-defendant’s murder.”

Foster is serving two life sentences — one for murder, one for armed robbery —and is currently seeking a re-sentencing hearing.

He is 41 years old.