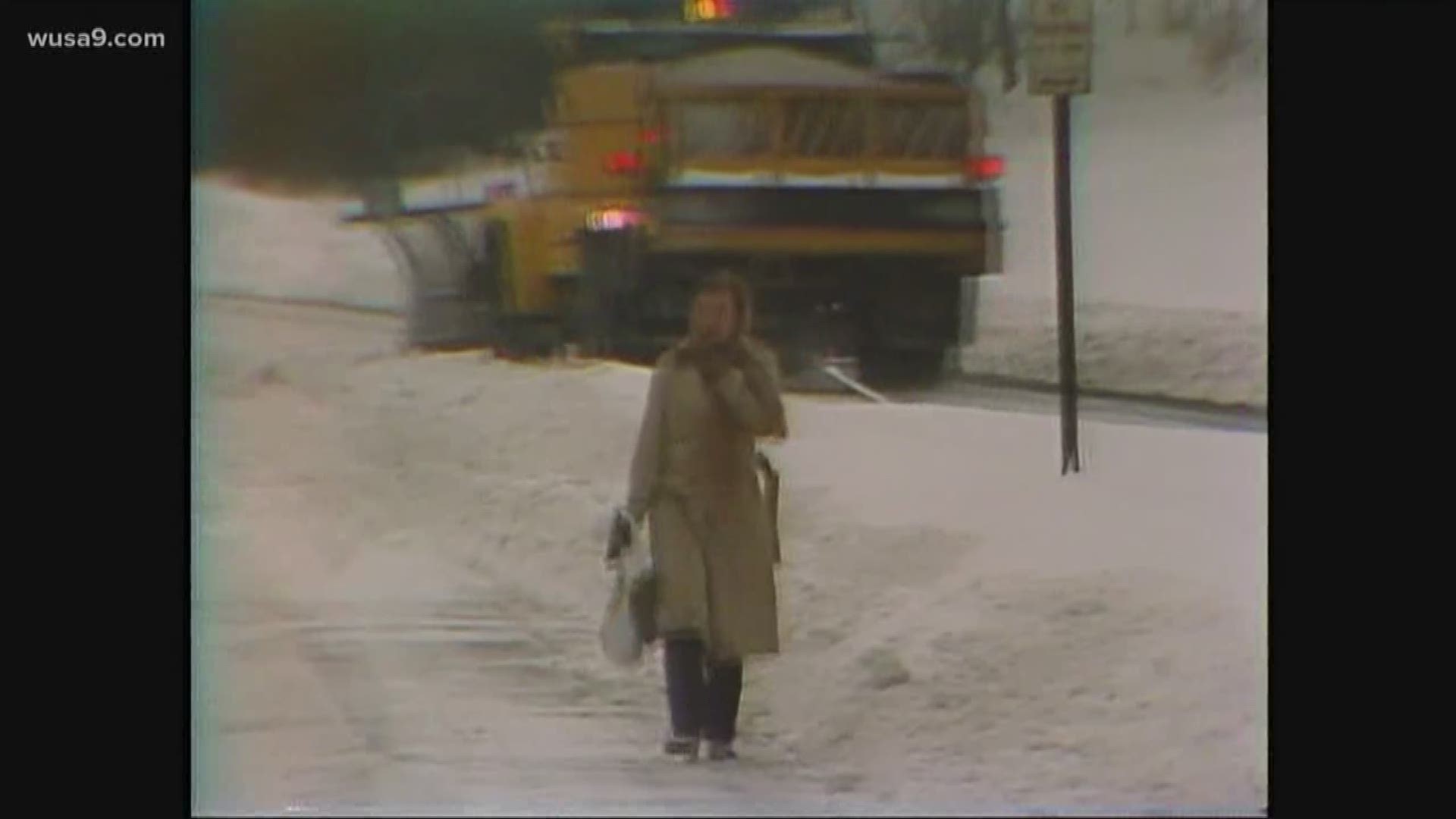

WASHINGTON — It was snowing when Joe Stiley woke up on the fateful morning of Jan. 13, 1982.

He knew he had to fly to Florida for work that day. He was tasked with the unfortunate duty of announcing layoffs and was not thrilled to be leaving town. It was his son’s 13th birthday.

Unexcited about his work ahead, he went to the airport with an eye on the forecast. He was not sure they would even be able to get a plane out that day.

Boarding the flight, he noticed a variety of folks heading to the warmer climate. There were military men, college students, and families on board. He spent a moment talking to a pair of students heading back to school in Florida after spending their winter break in Washington D.C.

Little did he know, his split-second decision to sit in the smoking section of the plane -- at that time, smoking sections were allowed on aircrafts -- with his assistant, Patricia Felch, would impact the rest of his life.

After several delays due to the heavy snowfall, the plane was cleared for departure.

Stiley was not a nervous flier. He was a pilot himself and trained students to fly in and out of what was then known as National Airport. It was renamed Ronald Reagan National Airport in 1998, many pilots have said it is a hassle to get in and out of.

As the plane gathered speed for takeoff, he started to worry. They were not going fast enough.

“I knew we were in trouble as we went down the runway,” Stiley said. “I knew we had nowhere near the right speed.”

Stiley put his head between his knees in a safety position. His coworker next to him did the same.

The plane stalled mid-air and began hurtling towards the Potomac River.

THE CRASH

Later, NTSB reports would show the first officer shouted, “We’re going down!”

The captain responded, "I know it!"

The plane crashed into the 14th Street Bridge and then slammed into the water.

In all, 78 people lost their lives in the crash that day, including three infants. Only five survived.

“I found myself on the verge of blacking out,” Stiley recalled. “I said a brief prayer, ‘Please God take care of my son,’ and I didn't expect to regain consciousness.”

It took a few moments for the plane to sink to the murky bottom of the river, and Stiley awoke to icy water splashing him. He realized he was alive as was his coworker, but his feet were trapped and he was still buckled in. He wrought his feet free from the crushed metal, then helped Felch.

Despite the darkness, they could see a little bit of light from the surface. The two swam toward it, crawling over the two students with whom they had been chatting with seconds earlier.

“Now all of a sudden, I'm in a frozen river surrounded by shreds of yellow insulation that had been part of the aircraft moments before,” he recalled.

The two swam towards some of the floating wreckage where other survivors had gathered and held on for dear life.

“There we were in the middle of nowhere in the middle of that icy area,” Stiley recalled. “At some point, a male voice started saying the Lord's prayer so we all joined in on that.”

Minutes ticked by, as people gathered to watch on the bridge and along the waterfront.

From the bridge, people tried to drop ropes down to help the survivors. Another witness dove into the frigid water from the bank of the river but could not make it to the floating piece of the plane.

“At some point I heard whoomph whoomph of a helicopter approaching us and I knew somebody was on their way there,” Stiley said.

The U.S. Park Police helicopter first picked up a flight attendant who had survived, Kelly Duncan.

At one point, two ropes came down for Stiley and Felch. Another woman, Priscilla Tirado, had surfaced but was struggling. Stiley knew he had to help her.

Felch took one of the ropes, while Stiley did a half hitch around his body with the other. He grabbed Tirado, and they started to tow them toward the shore.

“They towed me in and all these big chunks of ice and I kept getting it in the chest,” he recalled. His ribs were breaking. “After four or five such impacts, I lost my grip on Priscilla Tirado.”

Another man, Lenny Skutnik, jumped in to help her to shore.

Stiley was hauled into an ambulance and went into shock. He woke up hours later in a hospital room with dozens of injuries.

“Just sitting here talking to you about this has caused me to reflect on things that I haven’t thought about in years,” he ruminated one gray morning in December at WUSA9’s request.

“There was nothing more that I could do. I did everything that I could do,” he recalled emotionally. “And I haven’t second guessed myself since. I’m fortunate that I was there to do something … [but] what kind of fortune is that?”

Walking the trail at the park next to the site of the crash, Stiley said he learned a tough lesson in the years that followed the day the plane went down in the river.

“I got quite an education in the year or two thereafter of what it means to be a survivor of a situation like that,” he said. “I saw some of the best and worst of human people.”

His mother took care of him while he recovered, carefully re-wrapping his bandages as he struggled to regain his strength.

But he also lost friends and his job.

“I had all these people that were my friends that needed to borrow a dollar when once they knew I had one, or thought I had one,” he recalled, with a tinge of anger in his voice. “I lost what I thought were friendships once I realized I was worth more as a banker than as a friend to some people.”

But he is thankful to have survived.

“I’ve seen my children grow up and become parents and grandparents and I wouldn’t want to do it again,” he said.

In his eighties, Joe Stiley now lives in a remote part of Mexico called Puerto Escondido. He runs a small bed and breakfast and spends his days relaxing at the beach. But the chronic pain from his injuries stays with him, as well as the terrible memory.

“I took a cold dip in a frozen river once and that was enough cold for me,” he said dryly.

HOW THE CRASH IMPACTED THE AVIATION INDUSTRY

The Air Florida crash had a profound impact on the aviation industry.

The crash marked the beginning of the end for Air Florida as a carrier. Company executives filed for bankruptcy in 1984.

According to an NTSB report, several factors contributed to the Air Florida crash of 1982. The plane was not properly de-iced during the snowstorm that blanketed Washington D.C. in a reported 6.4 inches of snow. As a result, the FAA changed de-icing regulations.

The pilots were found to have little experience flying in the snow and did not communicate properly when an error was noticed on one of their instruments. The Air Florida crash is often cited as contributing to the formalization of a concept known as “crew resource management,” which means if any subordinate flying spots trouble, they should voice their concerns loudly and be heard by management. An NTSB report on the crash indicates the first officer had pointed out incorrect readings from an instrument only to be dismissed by the captain.

According to the NTSB and FAA, Boeing changed the thermal de-icing system in the 737 models after crash so less ice would build up on the wings.

A sixth victim, later identified by the U.S. Coast Guard as Arland D. Williams Jr., refused help so the others be rescued from the icy river. He drowned before emergency responders could go back for him. The District of Columbia later renamed the 14th Street Bridge in his honor.

WATCH: ‘In an Instant’ is a series that features people who unexpectedly had their lives changed in one moment and how it impacted them going forward. Episode three features two women who miraculously survived being completely run over by a car and how it brought them closer to their friends and their faith.