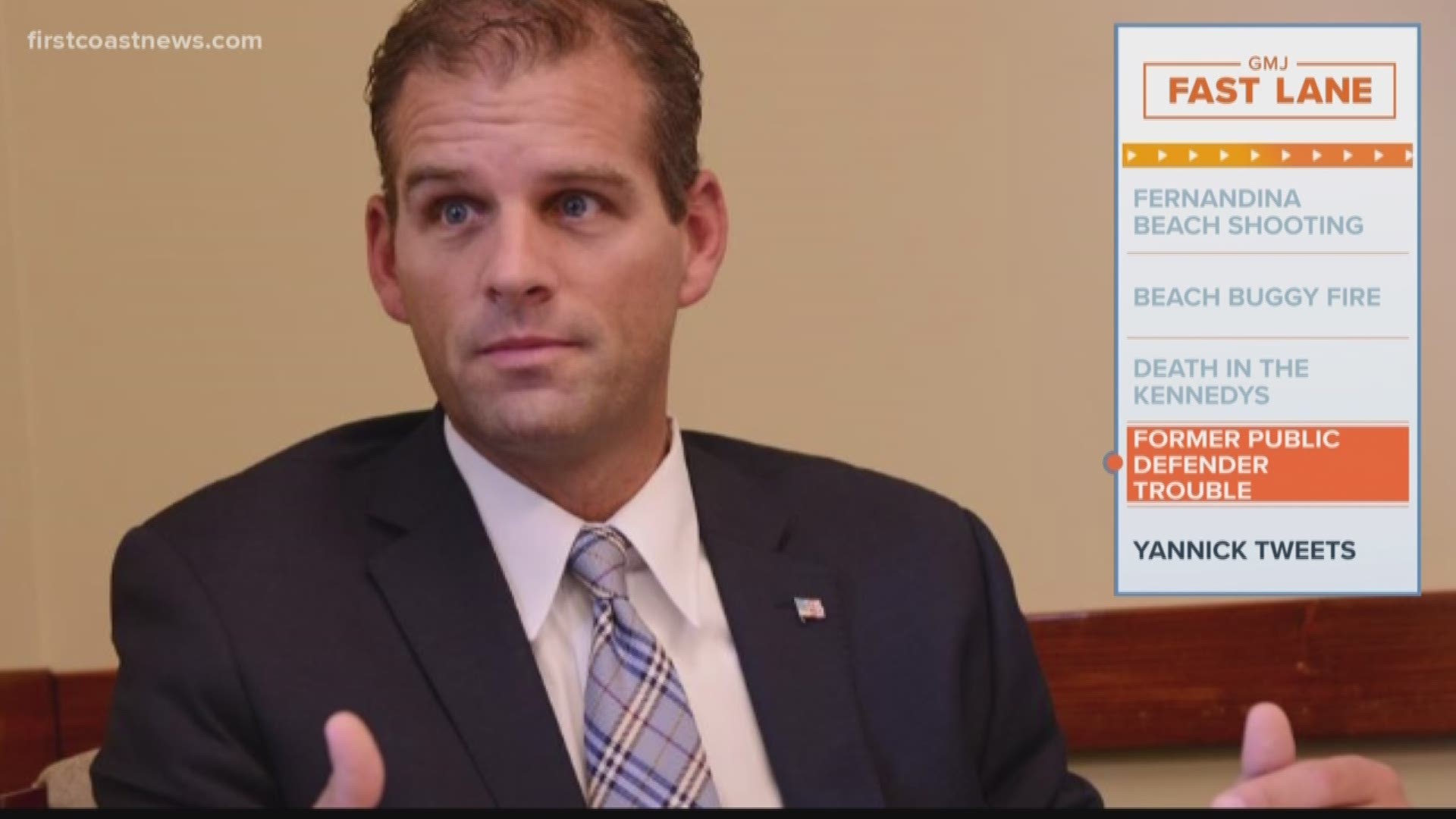

After former Public Defender Matt Shirk was ousted from office in 2016, he spent or gave away tens of thousands of dollars on himself and his friends, including handing nine state-owned firearms to a motorcycle club without documentation.

A new Florida Auditor General’s report, the culmination of more than two years of investigation, details the repeated ways that Shirk violated state law or policy before and after his failed August 2016 re-election bid.

The report details how Shirk used state employees to staff his personal nonprofit, Vision for Excellence, including assigning attorneys to work at fundraising events.

Because that nonprofit receives less than $50,000 a year, its financial records, unlike other nonprofits, is not publicly available from the Internal Revenue Service. This makes it unclear if Shirk was paying himself a salary from the nonprofit.

The auditor estimated the value of time Shirk’s employees worked at his non-profit as more than $14,000.

Among other things, Shirk still owes the state $5,242, and the auditor general has urged Shirk’s successor, Public Defender Charlie Cofer, to use a debt collector. Shirk owes the state because it paid for his retirement costs on his behalf, his personal fuel costs and costs associated with his damaging a car.

Public records also went missing during his final months in office. In one case, he gave away 10 computers just two days before leaving the office. When the computers were recovered, the hard drives had been removed and wiped clean.

“It is the belief of the present administration that the hard-drives had been removed from the computers prior to their donation to the charity,” Cofer wrote in a response to the report. “It is believed that the removal of the hard drives was part of a concerted effort by the prior administration to delete emails and other documents in violation of public records laws.”

Deleting public records can be a criminal violation in Florida. The Auditor-General recommended a number of policy changes to ensure these violations don’t re-occur, but Cofer responded and said, “It is difficult to successfully enhance controls to ensure the proper approval of [Tangible Physical Property] disposals if the head of the agency directs subordinates to violate those controls.”

Cofer’s response to the report said that Shirk “over-ruled staff concerns” before donating the computers.

Shirk did not return requests for comment Thursday morning, and he has not responded to any requests for comment since he left office in January 2017.

The Times-Union asked Thursday morning if the State Attorney’s Office will review the report for potential crimes committed. The office did not respond.

Former Jacksonville State Attorney Harry Shorstein said Shirk’s use of staff time for his nonprofit alone warrants an investigation by the State Attorney’s Office.

“You’ve told me of pretty widespread misappropriations on the part of the public defender,” Shorstein said. “I think the media has a duty to point out corruption, malfeasance, if for no other reason to put a damper on future public officials who might consider doing the same thing.”

He also said that grand jury reviews help deter public officials from violating the law.

Cofer said he told the State Attorney’s Office about many of these concerns when he took over the office in January 2017.

Following the Times-Union’s reporting in 2013 about past behavior by Shirk — including the illegal hiring and firing of some women, the deletion of records and the building of a private shower with public funds — Gainesville State Attorney Bill Cervone brought a case against Shirk to a grand jury. The grand jury declined to indict Shirk, but it asked then-Gov. Rick Scott to remove him from office, something Scott declined to do.

Thursday morning, Cervone said in an email, “Had a lot of those end of his tenure things happened when I was there the Grand Jury might have done something other than what they did.”

Cofer, who beat Shirk in the 2016 primary election by a three-to-one margin, invited the auditor general to investigate the office in April 2017. Cofer provided the office with a list of issues he wanted to be reviewed.

The Times-Union also requested all emails sent to or by Shirk in the calendar year 2016 in order to see if any emails appeared to be deleted. Cofer said the office only has eight emails sent from Shirk’s official account, and 217 emails sent to it for that year.

Cofer’s staff was able to also find another 1,057 emails sent to or from Shirk’s personal account that related to work. But some of those referred to emails from Shirk that the office didn’t have.

For comparison, Cofer said during the same time period in 2018, he sent or received nearly 11,000 emails from his official account.

One of Shirk’s post-election emails showed he criticized his employees for quickly providing public records to reporters. “I’m very concerned that multiple people in this agency have determined to drop the very important work that we do to make these requests their priority.”

Shirk still faces complaints from the Florida Commission on Ethics and the Florida Bar. He initially agreed to a settlement for his ethics complaint, but the commission rejected the settlement as not being harsh enough. The Florida Bar’s grievance committee reviewing his complaint has not yet determined if there’s probable cause that he violated attorney rules.

Cofer said he has drafted another Florida Bar complaint to file against Shirk, in addition to the one Shirk is currently facing.

Shirk gave away the nine handguns to a former employee who was a member of the Buffalo Soldiers Motorcycle Club. Cofer said there are no records that indicate Shirk ensured the people who got the guns were legally allowed to have guns.

Shirk also booked expensive travel, purportedly for office business, that included a $806-a-night hotel room in New York for an immigration law conference, despite the fact that state public defenders don’t practice immigration law. Since leaving the office, Shirk’s primary legal practice is now immigration law.

In total, he spent $4,010 on that New York trip, and he spent another $2,513 for a trip to San Diego to learn more about driving-while-intoxicated cases. He didn’t share anything he learned with his attorneys after the trips, Cofer said, which were both booked after he lost the August 2016 election.

Shirk wasn’t the only one booking expensive trips with state dollars after the August election. Justin Estes, who handled information technology for Shirk and had his salary more than doubled after the election, booked a conference in Los Angeles for more than $3,100, which included $900 for a hotel. Estes then resigned on Shirk’s final day in office.

The report also confirmed reporting by the Times-Union that showed in the days after he lost re-election, Shirk gave substantial pay raises to 14 employees, including Estes and other friends and political allies in the office. In some cases, he more than doubled their salaries. Nine of those resigned on Shirk’s last day, and a tenth was fired the next day.

In total, Shirk spent about $65,000 of the office’s budget on those salary increases. He did not have any justification for the raises. According to the report, Shirk did not always keep employees’ evaluations in their personnel files.

Cofer said Shirk did this in order to hide public records. “If he had a negative thing about someone he wanted to write it up, he didn’t put it in their personnel file. He’d do it in a memo and ... keep it in a separate file.”

State offices are supposed to follow a procedure before giving stuff away to ensure that the objects are actually surplus. The auditor reviewed how Shirk gave away $21,611 worth of stuff and found that more than half of the items — $11,764 worth — was given away without following any procedure. That included nine handguns and 14 computers, 10 of which were given on his second to last day in office.

Cofer alleged that those 10 computers likely contained public records that the office no longer has access to because the hard drives were removed. “I’m certain. I know there are public records gone. ... [IT Director] Joe Frasier in 2013, when everything was falling apart, did a backup of all the emails. ... most of those emails are no longer in our system.”

Estes told the Times-Union he believed his salary increase was justified. The day after Shirk lost re-election, he fired Frasier, Estes’ boss, which meant Estes had more responsibilities. One of those responsibilities, Estes said, included removing the hard drives from the computers. Estes said he did not delete information on the hard drives, but he stored them in a box in the IT workroom. He also said the December conference, which came just weeks before Shirk’s last day in office, was worth it because he learned a lot about computer security issues. Estes said that same month, Frasier told him he should probably start looking for new work, which is why he resigned from his job on Shirk’s last day.

Estes donated $200 to Shirk, and he said he’s never donated to another candidate.

The report also said Shirk gave $90,000 to a lobbying firm, The Fiorentino Group. The Times-Union had previously reported that Shirk had hired the group with state funds, but it wasn’t clear how much he had paid the group. According to the report, Shirk “selected the firm and developed the contract without staff involvement,” and there are no records that indicate he used a competitive selection process.

The Fiorentino Group then gave Shirk $1,000 in his re-election bid, and lobbyist Marty Fiorentino gave Shirk $500. A political action committee with the same address and suite number as the Fiorentino Group gave another $500.

Shirk’s was the only state campaign that Fiorentino donated to in 2016.

Estes said Shirk almost solely used his private email account, but there was no way for the office store emails that Shirk received or sent from that account unless he was emailing someone else in the office. For example, Estes confirmed, the office couldn’t retain any emails between Shirk and Fiorentino.

But Estes said he doesn’t think Shirk was technologically adept enough to know how to delete records.

The report also noted issues Shirk had with the two-state vehicles assigned to him. The state paid for his personal fuel usage, and he didn’t reimburse the state. He also got into a car crash about seven miles away from the office on a Sunday in June 2016, but he claimed he was working at the time. He did not say the nature of his work, though, and the report said it wasn’t clear why the state, rather than Shirk himself, paid $2,370 for the accident.

In an email a few days after the accident, Shirk told his assistant that the accident “was my fault. I was pulling out of a parking lot and sideswiped the bumper of another unoccupied vehicle. ... What do I need to do to be sure the other guy gets his vehicle fixed? Unfortunately, he drives a BMW but works for the Tom Bush and said the auto body there would do the work. I did not notify [chief investigator] Jerry [Coxen] and would prefer not to have others be involved in this.”

Shirk also owes the state for about $700 in fuel costs and $2,200 in retirement payments.