JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Bill Wirth was only 3 years old on Dec. 7, 1941, but certain things are unforgettable.

“My sister and I were probably ready to go to church, and we were outside playing,” Wirth remembers. "This guy comes jogging up the street, 'You kids get in the house now' he shouted at us.”

Wirth and his family lived about six miles from Pearl Harbor on Honolulu. The morning of the attack on the base and the weeks after were spent in his home, the nights in total darkness.

“They expected the next thing that would happen would be a Japanese landing force coming on, building a fortress to further attack the United States,” he said.

Terror.

They were in the dark, literally with enforced total blackouts at night. But also figuratively because they had no idea what was going on with Wirth’s father, Theodore, who was the Executive Officer on board the USS Portland.

While 2,400 Americans died that day, Dec. 7, 1941, Theodore and his crew were fortunate to avoid that fate.

They had been deployed offshore for exercises.

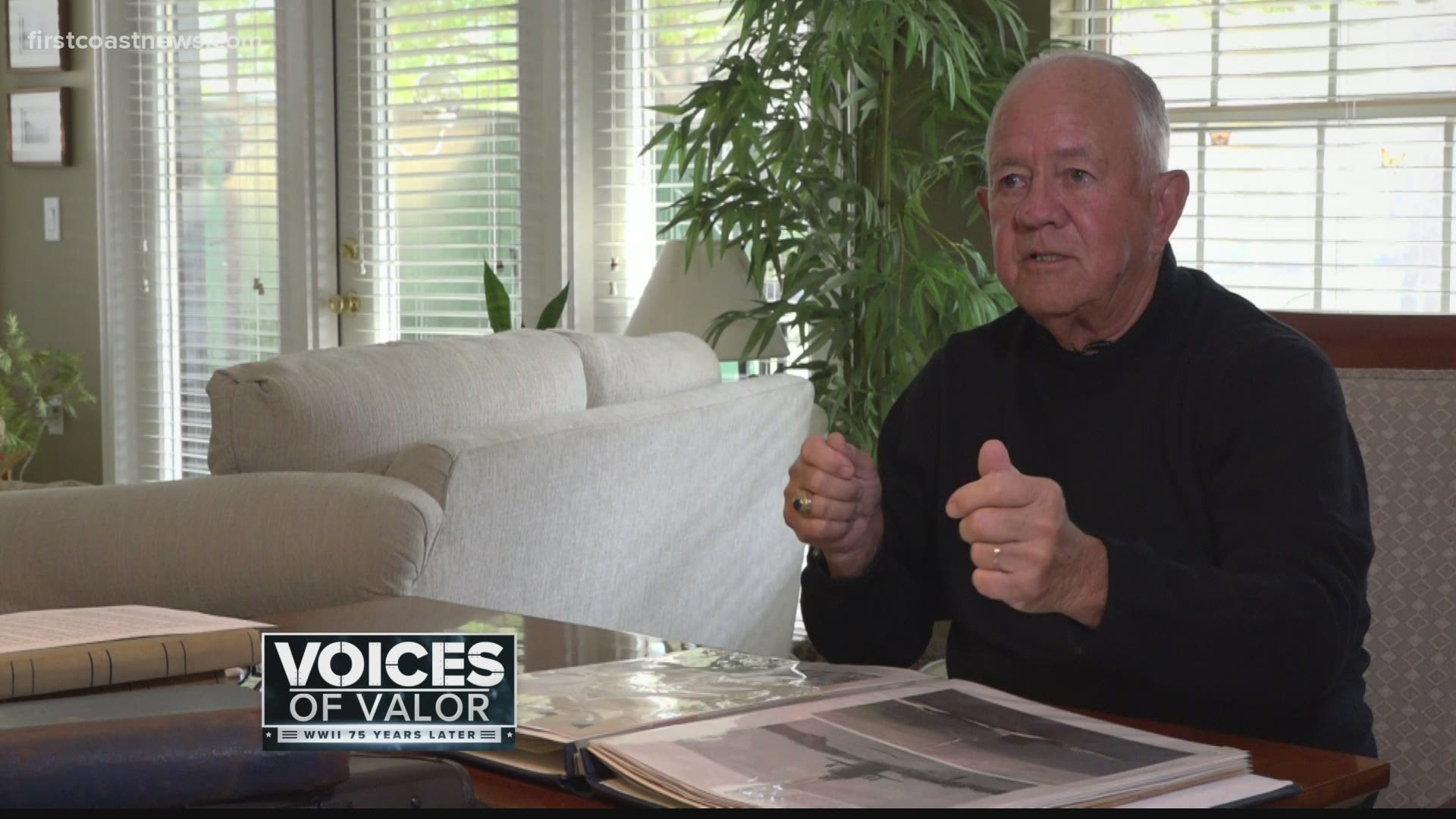

But about 10 years ago, a new light was shone on Wirth’s memories. His dad kept a journal from his time in the Navy.

And long after he had passed away, Wirth found the binders, even pictures in an old chest of drawers.

“They couldn’t believe what they were hearing on the radio, Pearl Harbor was being attacked,” he said.

And now Wirth finds himself reading this entry each Pearl Harbor Day.

“We just stood and stared," Wirth read from the diary entry. This account was from when his father's ship was coming back into the harbor.

"Gloom was as thick as fog and one wanted to cry," he read.

Robert Citino is one of the most distinguished World War II historians in the country and put simply he says: “The Japanese wanted surprise, they wanted to shock military planners and U.S. officers, and they certainly did.”

But Wirth's father had noted in his journal, despite the massive casualties and damage to the fleet, the Japanese still left the repair dry docks intact. He also noted that the fuel reserves on the base were left as well.

Citino says this indicates one of the crucial mistakes the Japanese made that day.

“If they thought a little more deeply about infrastructure, they might have put the U.S. fleet out of commission longer than they did," he said.

But it actually brought the U.S. into the war quickly, which led to what Citino says was Japan's second mistake.

"That was picking a fight with the United States in the first place," he said.

As for Wirth, he and his family moved back to the mainland shortly after.

He’d go on to the Naval Academy and was a submariner himself. He served primarily during tensions of The Cold War.

And he's now discovered new insight, and connection with his father he may have never had if not for his historic discovery in that old chest of drawers.