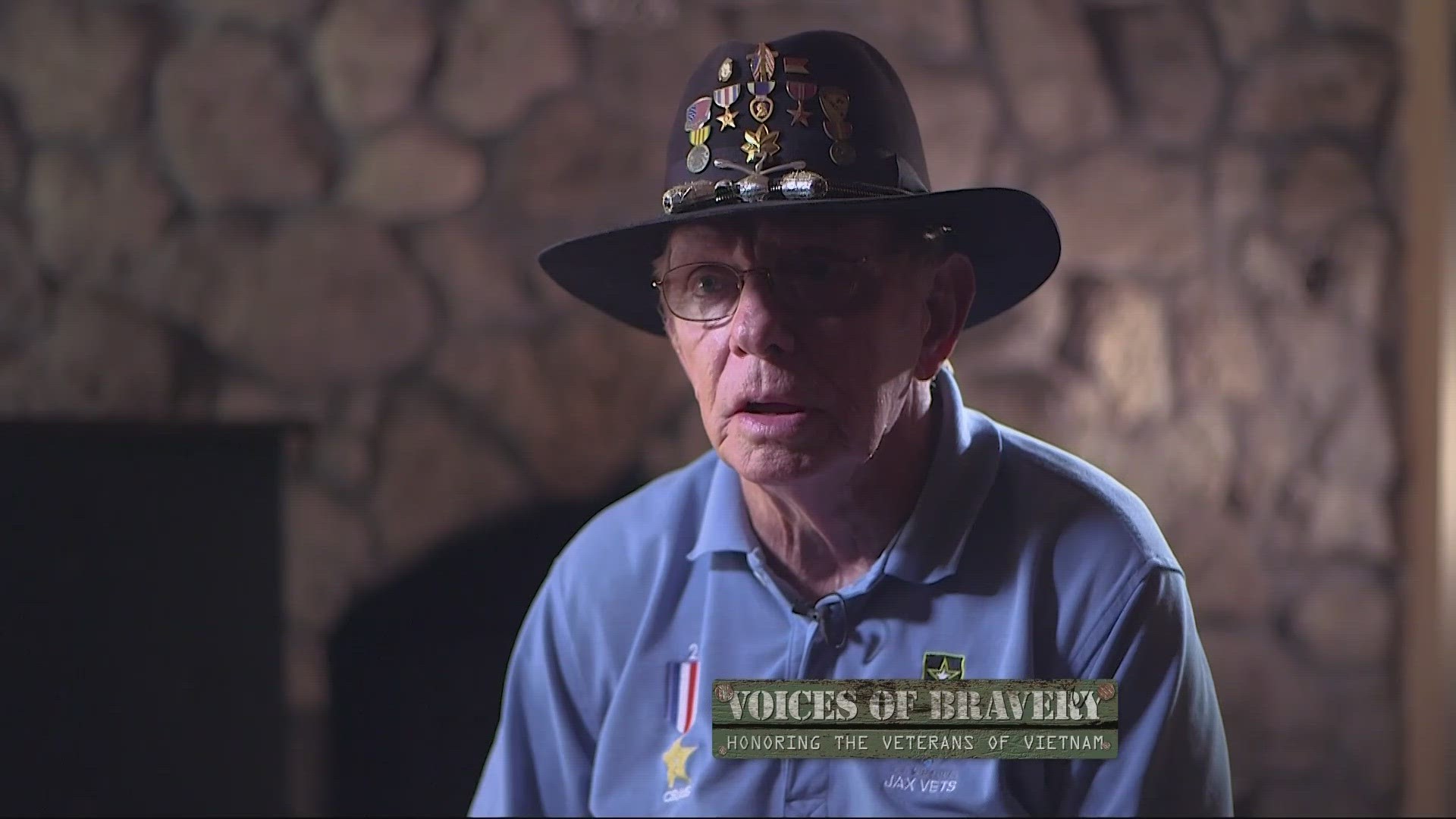

Honoring Vietnam veterans, commemorating 50 years since last combat soldier's exit | Voices of Bravery

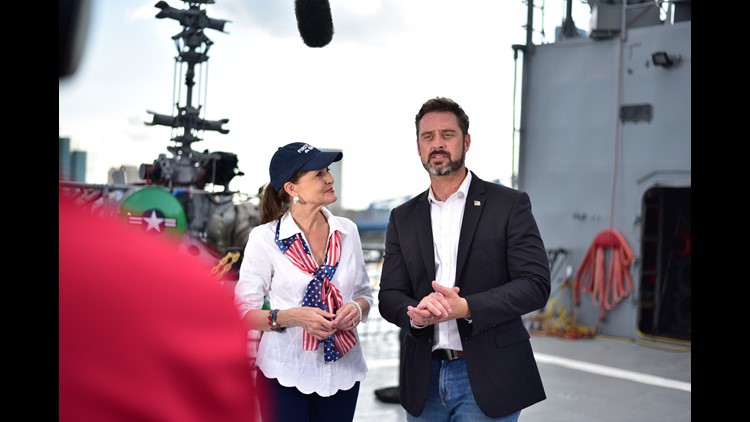

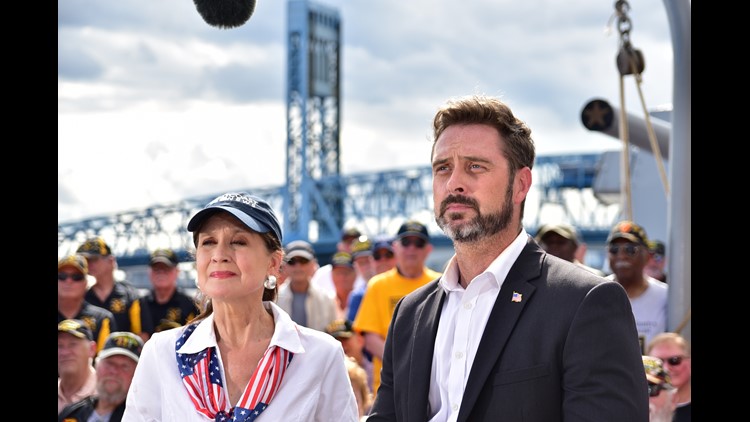

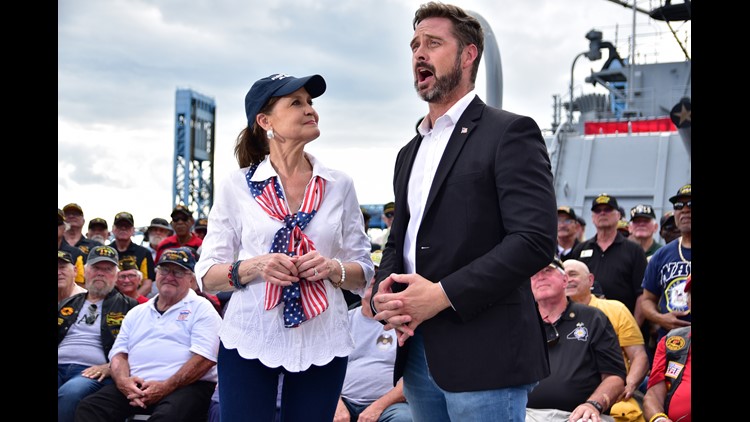

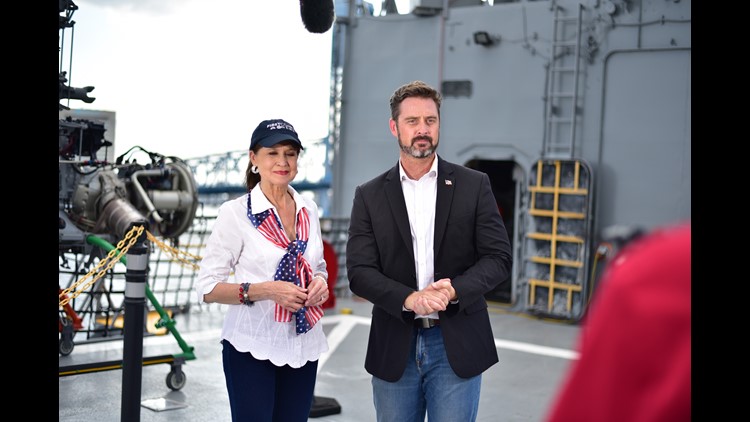

Jeannie Blaylock and Lewis Turner will tell the stories of Vietnam veterans celebrating those who served during a special report 7 p.m., April 13 on WJXX ABC25.

It’s been 50 years since the last combat soldier returned from the Vietnam War. To commemorate this, First Coast News On Your Side recognizes their bravery.

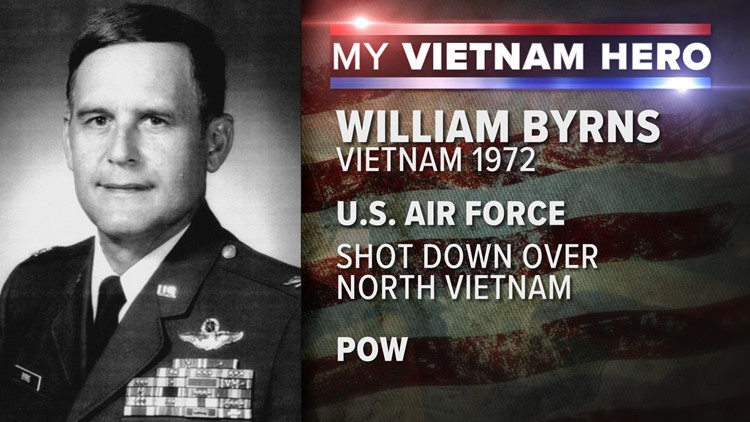

Anchors Jeannie Blaylock and Lewis Turner profile men who tell us they, ‘kissed the ground when they got home,’ and yet, in the same breath, describe how they were also spat on and called, ‘baby killers.’ Their stories will captivate you. What some veterans endured as ‘Tunnel Rats’ will grip you. The POW’s tell about torture, and, yet, pride in serving their country.

We invite you to watch Voices of Bravery: Honoring the Veterans of Vietnam to hear from local Vietnam vets on Good Morning Jacksonville at 6 a.m. and on First Coast News at 6 p.m. every day from March 27 through April 13th. Then join us for our special report – the stories of First Coast Vietnam Veterans and a tribute to them aboard the USS Orleck at 7 p.m., April 13, on WJXX ABC25.

The hour-long special reair on First Coast News+ on Roku and FireTV so you can watch on your schedule. The special will also be shown in Duval County Public Schools later this year as an educational tool.

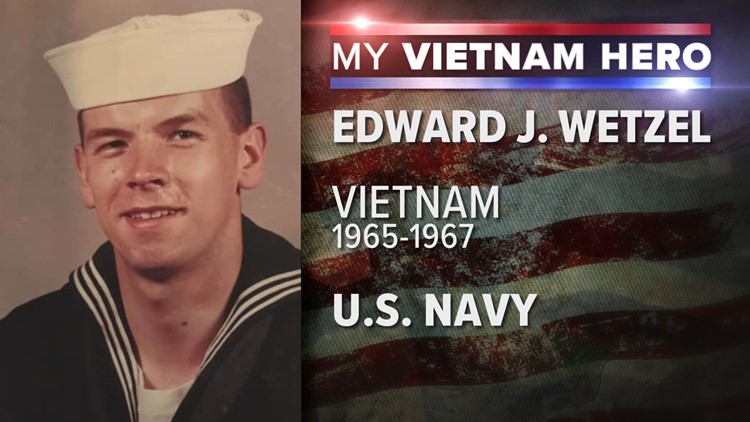

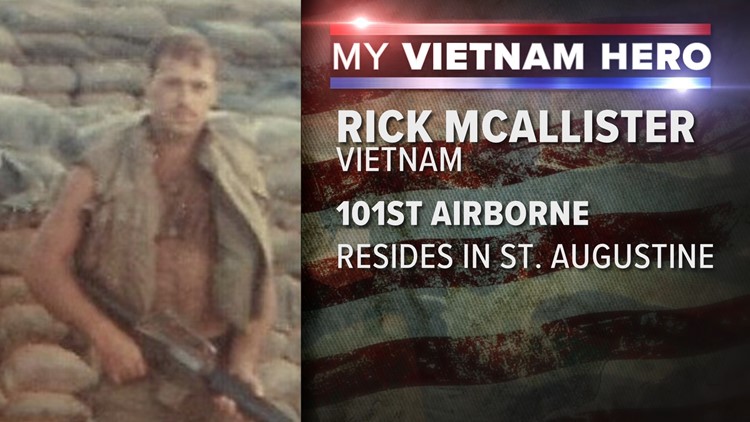

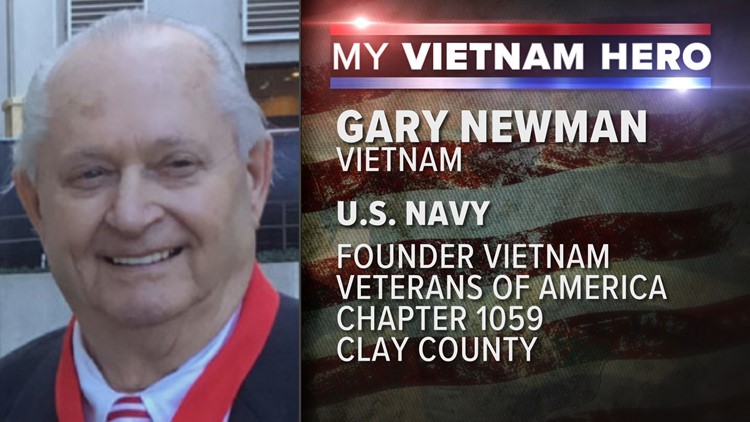

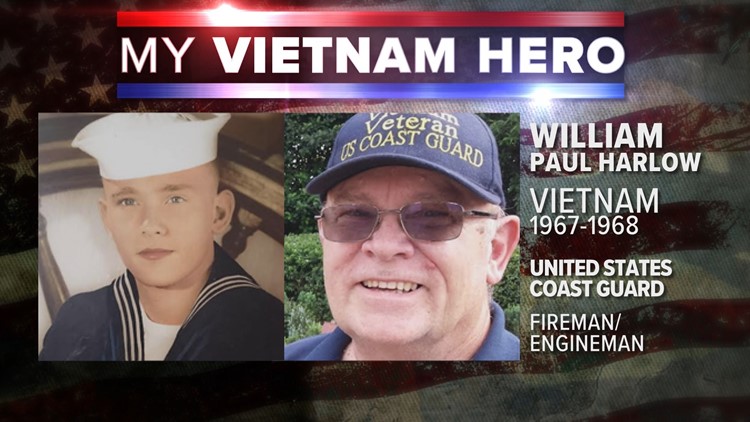

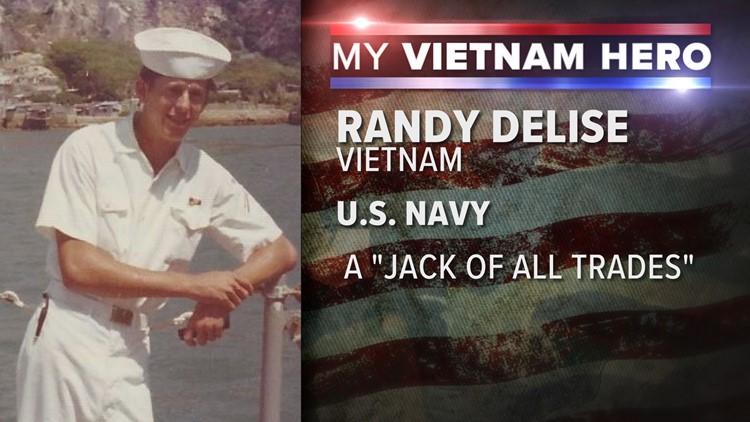

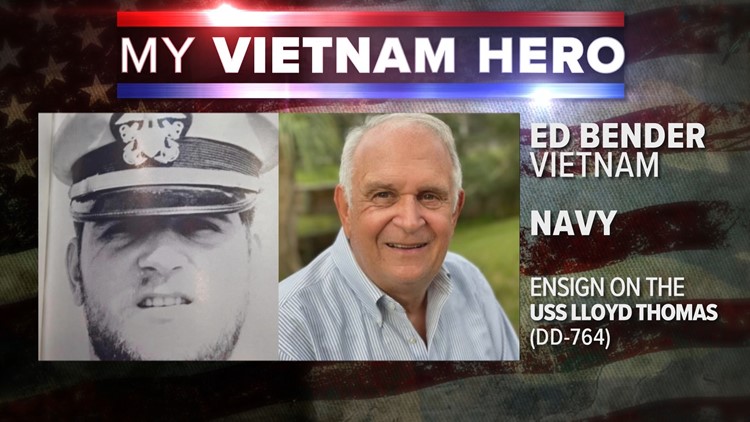

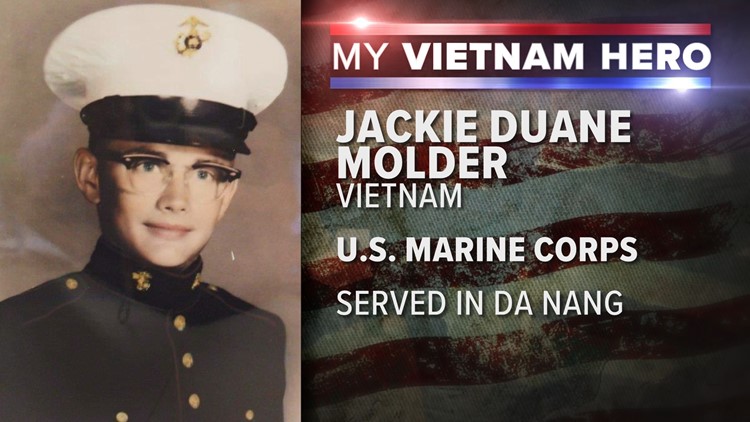

The following are stories we're sharing to honor those who served.

'Bamboo sticks filled with human waste' Tunnel rat describes dangerous job

It was one of the most dangerous jobs in Vietnam. A tunnel rat.

Sam Nelson, now a 75-year-old Vietnam veteran in Jacksonville, says he didn't even know what a tunnel rat was.

"When I got drafted, I weighed 100 pounds," he says. "In basic training, they said, 'You're going to be a tunnel rat.'"

He thought they were joking. "I didn't even know what a tunnel rat was," he says.

He was chosen for the mission because the tunnels were tiny, cramped spaces.

The most infamous were the tunnels in Cu Chi.

The Vietcong built more than 150 miles of tunnels on three levels during their war with the French in the 1940s.

They had hospitals in the tunnels, wards for birthing babies, schools, and hiding places for their own people.

And the dangerous part for our soldiers? The tunnels were filled with booby traps. Nelson says there were "bamboo sticks filled with human waste."

The enemy positioned deadly snakes in the pitch dark to attack our soldiers.

Tunnel rats had to crawl on their bellies, quietly, often with just a knife and a handgun to try and snuff out the enemy.

The casualty rate was high.

Nelson survived, though. But he had physical trauma. "I almost lost my feet. Every time I pulled off my sock, flesh came off."

Despite his bravery and despite his wounds, Nelson came home to a shameful reception. "When I landed in California, they were calling us 'baby killers.'"

He says now, 50 years later, he still can't understand why people would spit on him. "I thought we were serving our country, trying to be the best of the best," he says.

"I was ashamed to say I was in Vietnam," Nelson says.

Yet Nelson is active in the local veteran community. He wears his purple suit and drives a purple truck in recognition of all Vietnam vets who've been awarded the Purple Heart.

He's proud of his service in Vietnam.

Tunnel rats bring up a major issue of the Vietnam War and how the United States government handled it.

Dr. Michael Butler, historian and professor at Flagler College, takes his students to Vietnam to see the tunnels, as they are now.

He says they illustrate how the mighty U.S. tried "to fight a conventional war against an unconventional enemy."

The tunnels "were places where residents could use to escape the massive technological advantage the United States had," he says.

"Between 1962 and 1973, the U.S. dropped eight tons of bombs in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. That's three times the tonnage dropped in WW2," Dr. Butler says.

"The bombs didn't go deep enough into the ground... The Vietnamese were experts at using their environment to their advantage, and we did not comprehend," he says.

A terrible welcome home 'Baby killer! That's all you are. Baby killer!'

*Warning: Elements and video in this story may be disturbing to some.

Five Purple Hearts, four Bronze Star Medals and two Silver Star Medals.

And yet what happened when U.S. Army Major Craig Dunning got out of the hospital and walked into his life back in America?

"There was a fence," he says, and people were lined up. Did they cheer for him?

Absolutely not.

"They were calling us baby killers, they were throwing eggs and tomatoes." he says.

He wanted to yell back and "tell them to go to Hell." He says they weren't there. They don't know the struggles he faced every day.

"Everyone made me feel ashamed," he says.

And for decades the shame ate him away. At one point, he says, he attempted suicide.

"All I can do is pray, please let me forget," Dunning says.

But how did the terrible label of "baby killer" ever jump into the scene of Vietnam vets returning home?

Dr. Michael Butler, historian and professor at Flagler College, says one cause was the My Lai massacre in 1968. More than 500 unarmed Vietnamese villagers slaughtered including girls, old men and pregnant women.

"We're talking shooting, bayoneting, bashing skulls," Butler says.

A platoon of soldiers from Charlie Company were sent in to an area considered a communist center for activity.

Butler says the area was labeled part of 'Pinkville'.

Eventually, gruesome photos of the massacre hit the American press. "Once you see it, you can't unsee," Dr. Butler says. And then, he says, "The label 'baby killer' stuck....even though not all veterans were baby killers. Period."

The terrible treatment scarred Dunning. Even 50 years later, he was angry with the United States government, the politicians who ran the war from Washington.

He began writing his story. "I can see them sitting in Hell with the devil," he wrote.

He says the blame is on them. In his words, "The prominent fat politicians in Washington DC sitting on their fat asses making all the wrong decisions, justifying getting more American fighting men killed."

He says too many bright young people were lost.

"They would be alive with their families, where they should be, instead of dead, in a box, in a country they knew nothing about -- -fighting a war they didn't understand. May God hold them in His loving arms forever. Amen."

Dunning passed away on on February 20, 2023. His friends say he had no family to attend a service. They say he died from causes related to Agent Orange.

His fellow Vietnam veterans held a memorial for him.

The start of a living hell POW Pete Schoeffel describes enemy torture

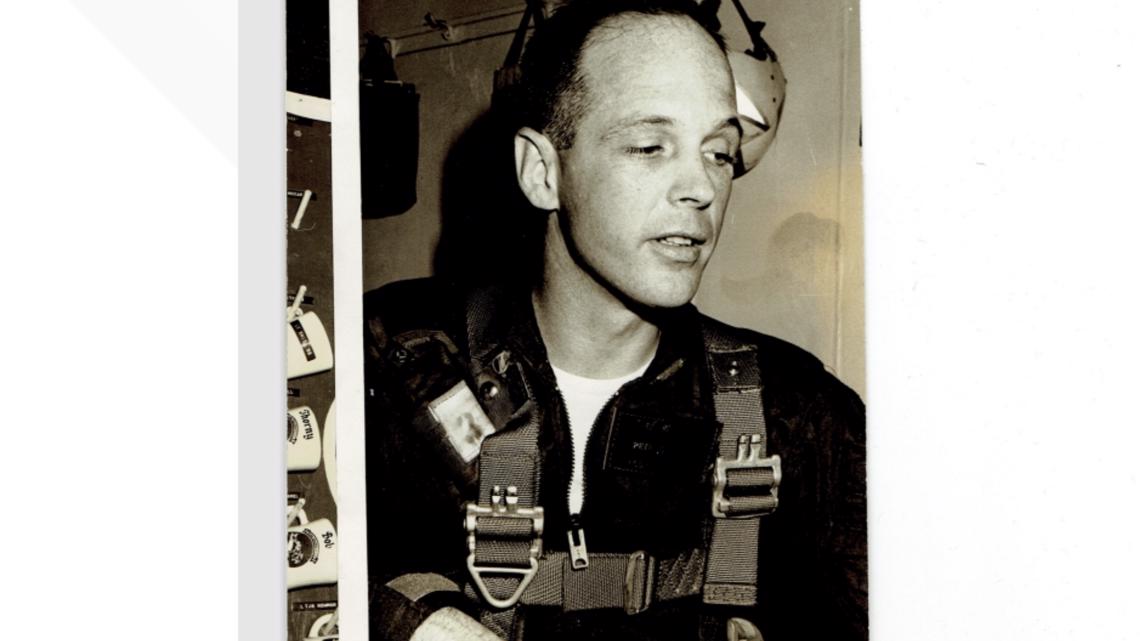

"You can't breath because your chest is compressed during the process," Captain Peter Schoeffel explains. He's talking about being tortured by the communist North Vietnamese, who were trying to force captured American military personnel to talk. Schoeffel, a retired navy pilot living in Jacksonville, tells about his experience as a POW in Vietnam.

He described how he would be handcuffed and shackled. He says he couldn't support his body after a time and wound up lying on the ground. "I'd be on my side sweating so hard I'd have a pool of sweat under my head and so I'd lean over and suck it up," he says.

Suck it up to get some moisture in his mouth...

Schoeffel was a POW in the infamous "Hanoi Hilton" for 5 1/2 years. During his captivity he would see another POW, John McCain, the U.S. Senator who ran for president.

Schoeffel would write poems with ink, made from "brown bombers," the name prisoners would sometimes give diarrhea medicine.

He used part of a cigarette package as paper. His words, written in tiny script, described his emotions in prison, "Here, twisted in a choking knotted hell, You strove to save your broken pride, And failing, heard its never-ending knell, And mourned you had not died."

First Coast News shared Schoeffel's story 30 years ago in a documentary on Vietnam.

Now three decades later, we get an update on Schoeffel, who's now 91 and getting around quite well. He's still sharp and still proud he flew for the U.S. Navy.

He says, over the years, a bright spot was having Senator McCain as the best man in his wedding. Another bright spot, his wife, Jane, and his dog, Bonnie.

And now that he's had years to ponder his experience, some dignified tears well up in his eyes, when he talks about his release from the prison in Hanoi.

He says, "None of us was sure it was really going to happen." They had no trust of the North Vietnamese, of course.

But they were loaded onto an airplane.

Still...with worry and doubts.

Then, he says, "The airplane did roll out to the end of the runway and did take off. And still we weren't so sure. Who knows the naughty things the Vietnamese were going to do. But then the pilot said, 'Wet feet.'"

That's the term meaning from land to sea, he says.

"Everyone broke out and screamed and yelled. And it was a wonderful feeling," he says.

And here's where he gets choked up. "It was late, 12:30 or so, and we landed in Hawaii. We were met by a great group of people, who just wanted to say, "Welcome home.'"

He pauses.

"It was one of the greatest feelings in the world," he says.

Certainly a welcome home celebration is not what every veteran received. Too many were treated like dirt. But for Schoeffel and other POW's, there was an organized effort to show respect.

Schoeffel says he doesn't want to spotlight on him. He wants our country to show respect to all the Vietnam veterans.

'I can't give back enough' Incarcerated veterans walk in circles for milles to donate thousands

You might think they'd blame Vietnam for their situation -- many locked up for life for terrible crimes.

But blame the trauma of fighting in Vietnam? No.

The Vietnam Veterans of America --VVA -- Chapter 1080 inside the Union County Correctional Institute was awarded best chapter of incarcerated veterans in the country in 2017.

First Coast News' Jeannie Blaylock interviewed some of the veterans and heard them say things, such as, "I can't give back enough. I screwed up. Yes, I screwed up."

Chapter President Ed Shook said a "bunch of us old guys" do walk-a-thons to raise money to give back to the community.

One of the group's sponsors, not an inmate himself, is Vietnam veteran Col. Bob Adelhelm. He says, "This VVA chapter has raised $34,000 over the last seven years and given it to the community."

But how do you raise money from inside a prison?

The walk-a-thons entail actually walking in circles, often for a couple of days in a row, around the prison yard.

And Shook's legs the next day? "Sore," he says with a smile.

You might not think there would not be much to smile about facing the rest of your life behind bars, but the VVA Chapter members say working to help others has been remarkable therapy for them, even for struggles with PTSD.

The prisoners have raised money for local schools and for local veterans.

For example, First Coast News aired a story about Chris Langston, who served in the United States Marines. His home burned down, and he was in tears, as he pulled out his father's uniform, tattered, pretty much in ashes. Through tears, he said, "These are my dress blues. These are my father's dress blues."

The inmates say they were watching First Coast News and saw his story.

At the next meeting they voted to donate $1000 to Chris.

Chapter 1080 has also worked to support Buddy Check and the Buddy Bus, a mobile mammography project between First Coast News and Baptist/MD Anderson. They've donated walk-a-thon money to help buy the Buddy Bus.

As one incarcerated veteran says, "We done something to take away from society and this is our way, as veterans, to give back."

They also ask for more respect for all Vietnam veterans, as they still express - some 50 years later - their pride in serving in Vietnam.

POWs set free. What did they talk about on that plane ride home? 'I didn't care if I lived or died'

"They would put me in a bamboo cage, not let me go the bathroom or anything," Dr. Hal Kushner explains about his initial time as a POW in Vietnam.

He remembers the night in 1967 when terrible weather took their helicopter down in Quang Ngai province in Vietnam. "I ran my tongue over my teeth. I remember vividly...I was missing a bunch of teeth. I lost seven teeth," he says.

He was a POW for 5 1/2 years or 1,932 days.

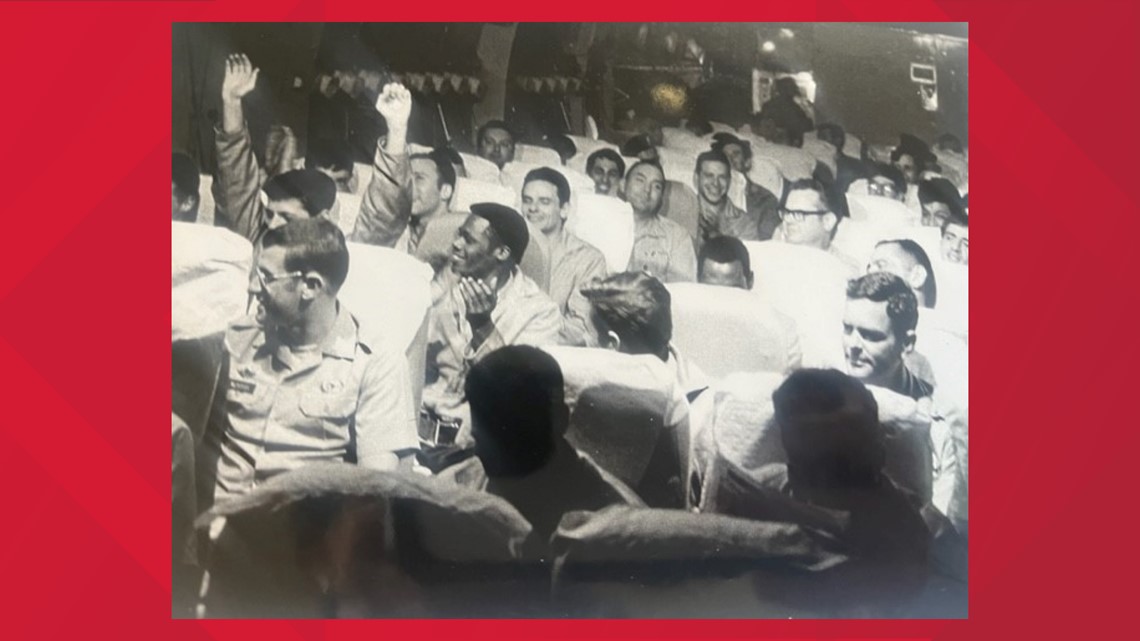

Fifty years ago, after the Paris Peace Accords, hundreds of American POWs were released.

"I was overwhelmed, I'm overwhelmed now just thinking about it," Kushner says.

And you may wonder what the prisoners - finally free - talked about when they were flying home to their families.

Kushner says there was very little talking. Instead, they were reading.

"They gave each man a folder," he explains. Inside was news customized to each former POW. It could be their mother had died.

"Some wives had left their husband and run off with somebody else," Kushner says. The folders contained, he says, "news about family, plus news about the moon landing, who had won the Super Bowls" and more.

Back on American soil, Kushner broke into a song, "America the Beautiful." He says, "I promised myself" to sing it to mark the homecoming. The photo shows Kushner at the microphone.

He says his hometown treated him well. He says people would drop off steaks and the community gave him an Oldsmobile, which he drove around the country to speak personally with families of his fellow POWs who'd perished in captivity.

Kushner was born in Honolulu, Hawaii in 1941. His father was serving with the Army Air Corps. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Kushner was just six months old. The attack was close to his family's home at Hickam Air Field.

Kushner comes from a line of proud military service.

And he does not speak with one word of bitterness about his service in Vietnam, despite his years of torture and starvation.

He says at times he thought, "I'm going to lose it. Go crazy. Go insane."

He says, "I didn't care if I lived or died. I'd hear artillery close to us and I didn't give a damn. Blow me up."

At other times, "I thought they can't kill me. I'm invincible," he says.

One of the worst traumas for him was watching his fellow POWs die. In fact, he says, he had ten die in his arms.

"I held their heads in my hands as they passed to the other side," he says. As a medical doctor in Vietnam, he knew he could have helped them, but their captors did not allow necessary medicines or nutrition.

He returned home to practice as a surgeon in the field of ophthalmology.

Now, in his 80s, Kushner rides an exercise bike and plays tennis. He says he's never experienced PTSD, but he does experience distress when he thinks about the mistreatment and disrespect other Vietnam vets have experienced.

He blames the suits for the outcome of the Vietnam conflict, not the boots.

"We lost because the politicians refused to do what was necessary to win the war," he says.

Despite the sour chapters of Vietnam, Kushner says, "I'm proud and honored I could serve my country."

This photo shows POW Hal Kushner and fellow prisoners just released from prison camps in Vietnam. Kushner was held 5 1/2 years, 1,932 days

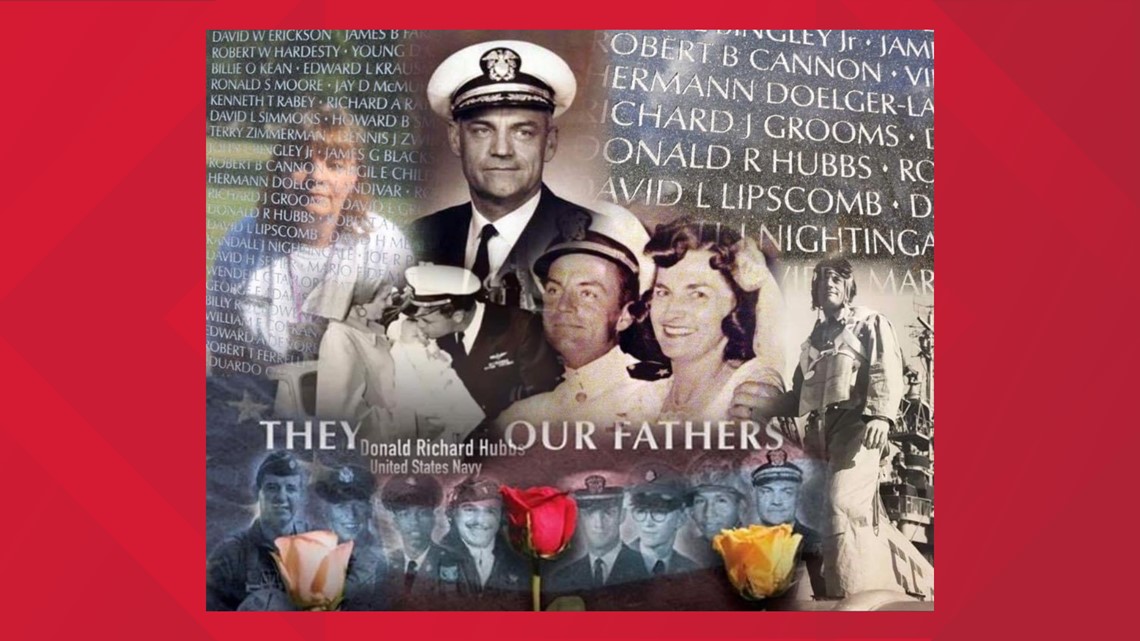

Former Jacksonville teacher looks for clues about MIA dad 'It's important for me to know what happened'

"People say you need to give up," says Jill Hubbs. "Let it go. But my answer is that you don't understand unless you've been there."

Hubbs was a teacher at Crown Point Elementary in Jacksonville.

She says she's not going to quit looking for clues about what happened to her dad during the Vietnam War.

"I love my dad," she says, and "it's important to me to know what happened."

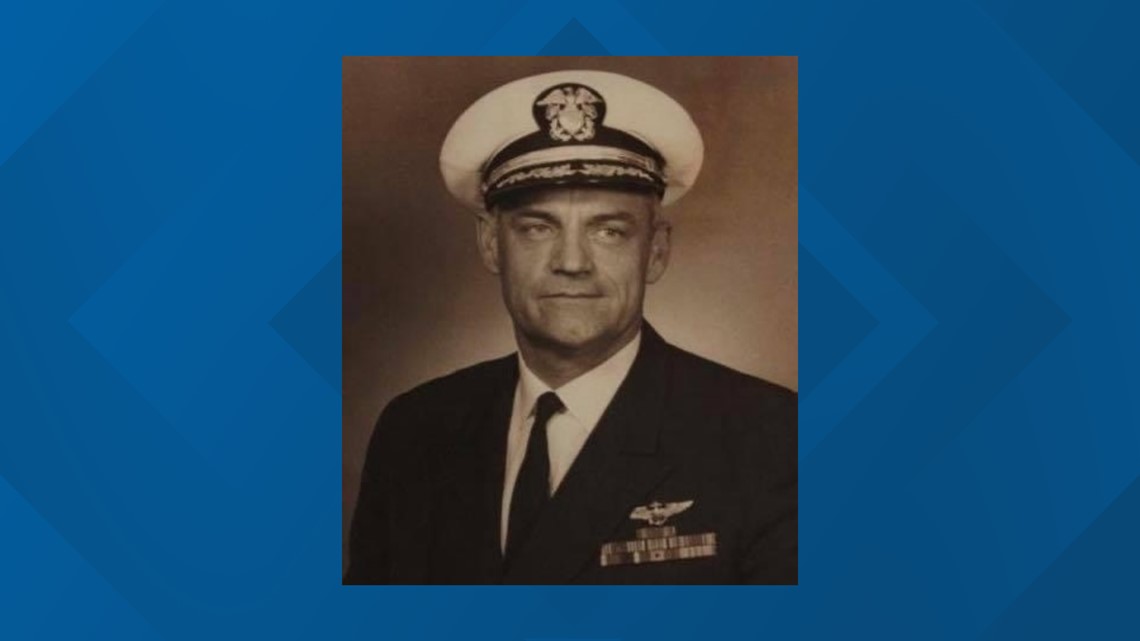

Hubbs has a recording of her dad's voice saying, "I'm honored to take command of the world-famous Black Cats."

Her father was proud of his mission in Vietnam. But in 1968. Commander Donald Hubb's S2 disappeared over Vinh, south of Hanoi.

At first there appeared to be evidence he could be alive. There was a short film clip of prisoners tending a garden and one bending over looked like her dad.

"He had the same hairline," Hubbs says.

Hubbs took a trip to Vietnam in 1993 to search for clues. She took pictures and sketches around Hanoi and just asked people if they have seen her father.

"He has scars here and here and here."

But nothing turned up.

She even went to Vietnam museums and looked through boxes of helmets and dog tags.

Now, decades later, her dad is most likely not alive. He'd be 96. And after the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, the POWs set free did not report ever seeing her father, Donald Hubbs, in any POW camp.

Her father is honored at the USS Yorktown because his S2 flew off that aircraft carrier. Hubbs went to visit the memorial. She crawled inside to sit in the cockpit, and she realized something else.

"There were no ejection seats," she says. It is another reason she thinks he may not have survived when his plane went down.

Hubbs has done extensive work with the other MIA sons and daughters.

She has helped unite the now-grown children to share stories and support each other. In fact, she produced a film called "They Were Our Fathers."

As a Gold Star daughter, Hubbs says some 20,000 American children lost their dads in Vietnam.

Hubbs is also on a mission to urge the federal government to step up its search efforts to find pieces of downed planes and remains of military personnel in Vietnam.

Twice she's been at the White House and talked face-to-face to Presidents Obama and Biden. She told them, "I'd like some answers. I want an underwater search."

She says DNA technology is already identifying fragments of teeth and bones for some MIA families.

She knows from radar and radio transmissions the exact spot in the Gulf of Tonkin her dad's plane was last heard from when he disappeared.

On another trip to Vietnam, she made a wreath with her dad's photo on it and took it to that exact spot.

"I said a little prayer. I put it in the water and let it go," Hubbs says.

But she isn't going to let go her quest to discover more information about her father, "my fishing buddy."

Made to feel ashamed, Vietnam vet grows out hair to look like a hippe 'Thanks for your service? Never, ever'

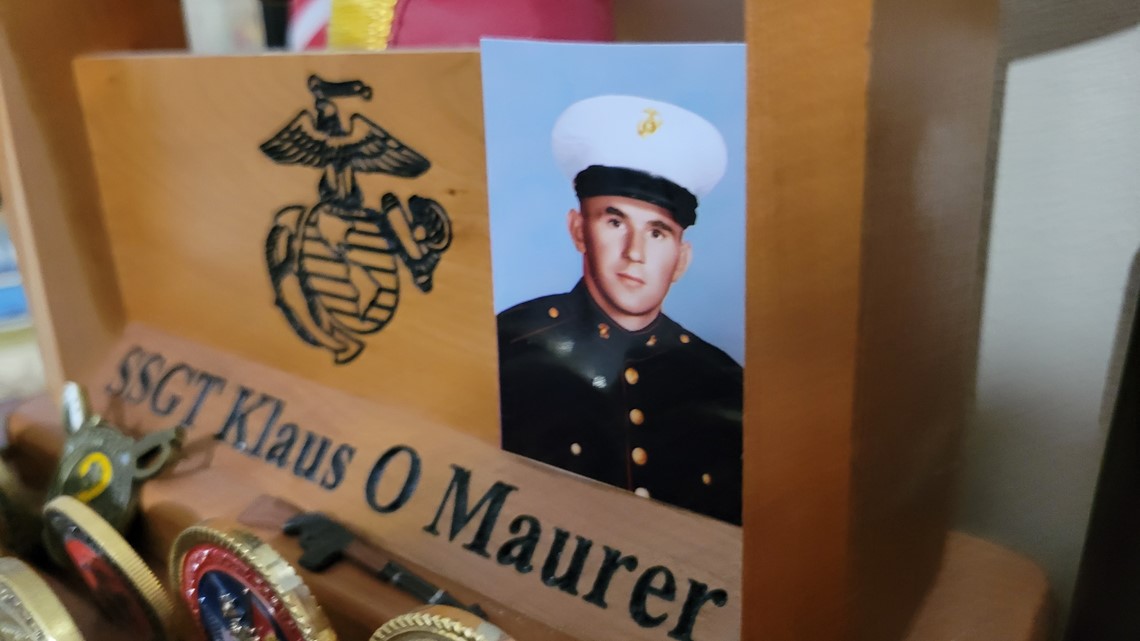

"Thanks for your service? Never. Ever," Klaus Maurer said about his return to the United States after serving in Vietnam in the United States Marines.

He's a Purple Heart recipient. And he's been awarded numerous medals.

And yet when he came home, "They put us on buses. The windows were all painted white." Why? "The government wanted to hide... not want to show the casualties," from the Vietnam War, he says. .

Then when he got to a base in Florida, a commanding officer told him, "Don't tell anybody you are a Vietnam vet."

So Maurer grew his hair long and put on bell bottom pants to look like a hippie. He blended in to avoid the "shame" people made him feel.

Yet he had gone to great lengths to serve in the U.S. military. And now, 50 years later, he is still proud of his service.

But his story starts back in WWII. His grandmother opposed Hitler and refused to salute him in a parade in Germany, where Mauer grew up. "The Nazi's horse-whipped her in the face," he says.

His belief in a free country grew even stronger over the years. Eventually he moved to the United States and joined the military.

And the pain of some of the experiences still makes him choke up.

He was a combat engineer. "We built bridges," he says.

But one guy was new. It was his first day when extra help was needed. He was a welder, and Maurer promised him he'd be safe, despite the anxiety the welder felt.

Then in just a few hours, a sniper shot him in the head. "His brains and everything rolled out of his head," he recalls, as he points to his own shoulder.

Maurer carried him back in the water, the body parts coming down. "It such a hard thing to see with his head blown off."

Since then, the guilt hasn't gone away. It's not his fault, of course, but he says, "I promised to take care of him."

As for his service and the dedication of his fellow marines, Maurer says, "We gave out best...We weren't politickers. We were soldiers."

He says it's never too late to give a proper welcome home to Vietnam vets.

Veteran says it's not too late to respect our Vietnam soliders 'You never leave an American behind'

Tony D'Aleo says he served proudly in the United States Marines.

He believes it's not too late to show more respect to our Vietnam vets, 61,000 of whom still live in the North Florida and SE Georgia area.

He is open about his combat experience.

Most painful are the experiences of losing a buddy in battle. "I had to hold his intestines in. He got blown up," D'Aleo recalls.

"I was trying to wrap him in a poncho to keep his intestines in his body," he says.

And the memory, has it faded?

No. Now, some 50 years later, he says, "I wake up with sweats. Cold sweats."

Agent Orange, battles with the Veterans Administration, and frustration over recognition for veterans' issues all plague D'Aleo.

But he still cannot forget the evil tactics of the enemy in Vietnam.

He says the American soldiers' bodies "would be mutilated." He says because 'you never leave an American behind," he and his fellow marines would come back to the battle site.

But there they might find their fellow marine butchered, his private part "put in his mouth," and his body wired to a tree, he says.

The tactic was evil and tricky. "We would find it and that was to get our minds crazy...'cause that would be the guy in our squad or our platoon. They used that to make us run" right into an ambush in a mad rush of revenge," he says.

He says some of their leaders figured out the strategy of the Vietcong and put a stop to the possibility of more fatalities.

He says, "I wish I didn't go to Vietnam." But he says, kids ask him why he went. His answer is this. "I went to help a country that was overrun."

But even all the trauma, D'Aleo continues to work in the community to garner more respect for veterans. D'Aleo was chosen for the Florida Veterans Hall of Fame. He's frequently at veterans' gatherings, such as the Semper Fidelis Society, to encourage his fellow vets.

'It changed my life' Agent Orange eats away at Vietnam veteran

Agent Orange was used by the United States to deforest, defoliate and kill as much vegetation as possible to take away the ambush hiding spots of the Viet Cong.

Soldiers sprayed it from river boats and dropped it on forests from the sky.

And no one could hide from it.

Tony Mann’s raspy voice tells a piece of his Vietnam story and likely will for the rest of his life, having suffered throat injuries from exposure to the omnipresent chemical.

“They go down and clean up and check the esophagus, make sure there’s no cancer," Tony says of his frequent trips to the VA. "They burn off the cells, send em in and find out what the status is.”

Despite his health struggles, Tony says he was honored to serve in Vietnam.

“I joined the service to serve my country and I served it very proudly.”

Honoring Vietnam veterans on USS Orleck

Voices of Bravery | Vietnam heroes