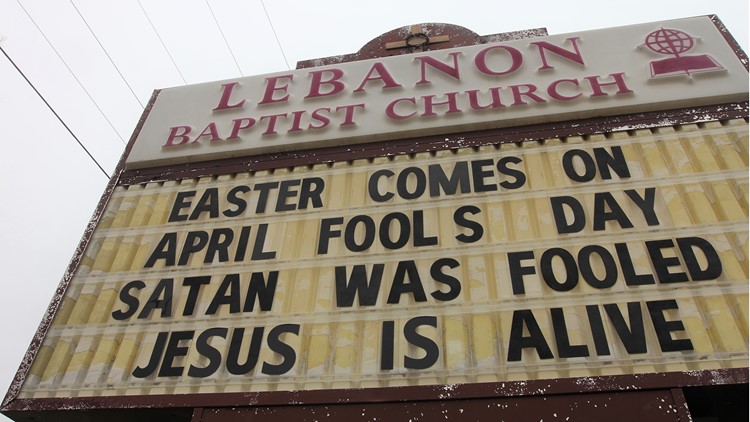

Easter falls on April Fools' Day this year, the first time since 1956, and the joke writes itself.

There's a million ways to tell the wisecrack — considered by some historians to be the greatest prank in history — but the root of it goes like this: Jesus died and was resurrected three days later, the ultimate prank on the devil, said Cal Samra, editor and publisher of The Joyful Noiseletter, a magazine devoted to religious jokes and joys.

"You talk about a major miracle? This is it," he said. "Early Christianity had a tremendous amount of joy, humor."

From April feasts to April fools

The origins of April Fools' Day are murky at best.

Long before the advent of April Fools' Day, there were religious and agricultural celebrations in spring. Today the spring comes after people have been cooped up, but back then it was more about surviving winter, said Max Harris, author of Sacred Folly: A New History of the Feast of Fools.

One idea is that clowning around in the spring is an age-old tradition that's universal after hard winters, he said. The joyous religious celebrations around spring include the Hindu festival of colors, also known as Holi, and the Jewish holiday of Purim.

The oft-cited Feast of Fools in the Middle Ages, long thought to be an ancestor of April Fools', has no direct connection aside from the word "fool" and was a New Year's Day celebration, said Harris, whose work challenged the assumed connections.

During the Feast of Fools, lower-ranking priests would be allowed to lead services in place of higher-ranking priests or bishops but there was no tomfoolery or funny hats, Harris said.

One of the religious precursors to April Fools' Day was risus paschalis, or Easter Laughter, a ritual in southern Germany in the 15th through 17th centuries, said Bernard Schweizer, a Long Island University professor who has studied and written about religion and humor.

Priests would urge their congregations to laugh out loud on Easter, telling jokes inside the church, said Schweizer, who communicated through email while in China.

"Easter was an occasion for joy, and collective laughter was seen as the strongest, most direct expression of joy," Schweizer said.

The Easter Laughter was prohibited by a papal order in the 1600s because of a pope's concern about mocking Christianity, he said.

It was one of a series of ups and downs for Christian humor, said Samra, of The Joyful Noiseletter. When Christianity becomes too serious, a new generation always brings back the joy and laughs.

"The Apostle Paul said we ought to be fools for Christ's sake," he said.

There's a lot of good when Christians laugh and enjoy life, said Father Dwight Longenecker, of Our Lady of the Rosary Catholic Church in Greenville.

He said the root word of humor is the same as humanity. Joy, laughter and fun are all parts of being good Christians, he said.

Explaining the joke

The theology behind "Jesus pranked the devil" is a bit more complicated than it appears, said Schweizer.

He said the so-called prank was given heft by religious scholars, including Irenaeus, who was a second century Greek cleric, and St. Augustine of Hippo, some 200 years later.

It's known as the ransom theory of atonement and essentially says God tricked the devil by offering the sinless Jesus as a sacrificial ransom to release humanity from the devil's bondage, Schweizer said. The devil got more than he could expect and accepted Jesus' death as a sort of payment, he said.

"But in the resurrection, it became apparent that the devil had been tricked since Christ could not lastingly die. Satan lost his payout," Schweizer said.

This theory, however, raises problems for today's theologians, "To think that God would be negotiating with the equivalent of a 'terrorist' and using Christ's life as a decoy," Schweizer said.

A passage in the Bible reads: "... the man Christ Jesus; who gave himself a ransom for all," is used to bolster the ransom theory.

But Walter Johnson, a Christian studies professor at Northern Greenville University, said the word ransom in the passage isn't taken literally by most religious scholars today.

The ransom theory also means the devil wouldn't have known Jesus was God's son or would not have understood Jesus could not be killed, Johnson said. For those and other reasons, most religious scholars today don't buy into an explicit ransom theory, Johnson said.

Early theologians, including Gregory of Nyssa, would revel in the idea of the resurrection as a practical joke on the devil, Johnson said.

Saying Jesus or God played a joke, or deceived or bested the devil, is great material for sermons. It's an effective parable and it's fun to say, but it doesn't hold up to most scholars today, Johnson said.

He said theologians go with many other theories of atonement or resurrection, including the satisfaction or restitution theory, which holds that Jesus' great sacrifice satisfied God as no human restitution could have done.

But there's a beauty in the resurrection and its twist ending, said Father Longenecker.

"Jesus' resurrection is the biggest surprise that ever happened," he said. "It's the divine joke that saves us."