WASHINGTON — Republicans say they won’t raise taxes on corporations. Democrats say they won't raise taxes on people making less than $400,000 a year. So who is going to pay for the big public works boost that lawmakers and President Joe Biden say is necessary for the country?

Enter the IRS.

Biden is proposing that Congress build up the depleted and often-maligned agency, saying that a more aggressive collection of unpaid taxes could help cover the cost of his multitrillion-dollar plan to boost infrastructure, families and education. More resources to boost audits of businesses, estates and the wealthy would raise $700 billion over 10 years, the White House estimates.

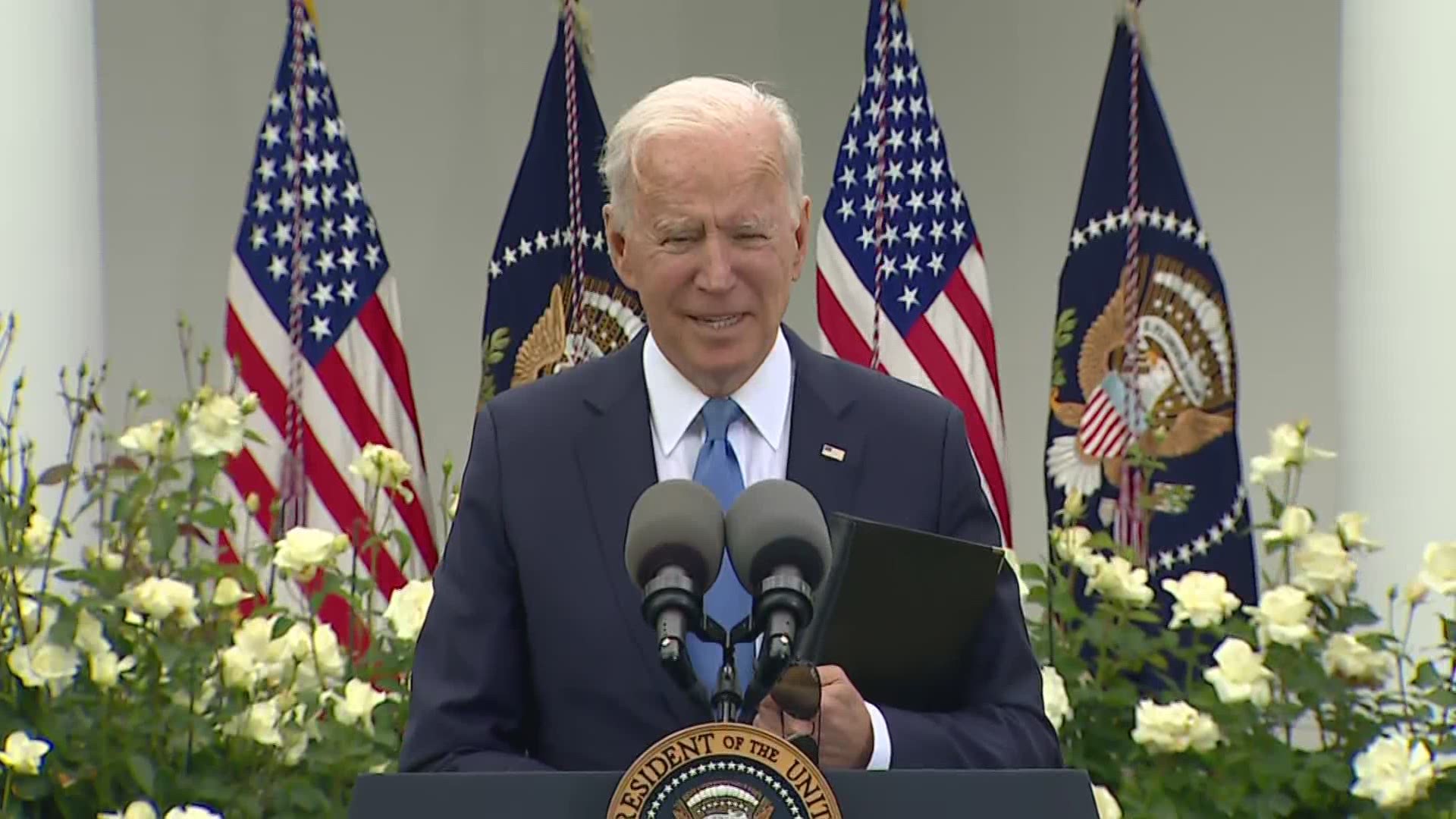

It's just the latest idea emerging in the bipartisan talks over an infrastructure bill, which saw Biden huddle at the White House this week with congressional leaders and a group of Republican senators. The GOP senators, touting a $568 billion infrastructure plan of their own, said they were “encouraged” by the discussion with Biden, but all sides acknowledged that how to pay for the public works plan remains a difficult problem.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said Biden brought up his IRS proposal as he met Wednesday with the top four congressional leaders.

“My understanding is it’s at least $1 trillion, it could be a trillion-and-quarter, a trillion-and-a-half dollars of illegally, unpaid taxes in the country,” Pelosi said. “Part of the answer is to beef up the IRS so they could take in those taxes, and that’s a big chunk. That could go a long way.”

She was referring to the tax gap, which is the difference between taxes paid and taxes owed. In a politically charged climate, there isn’t agreement on how big the tax gap is, let alone how much of it could be captured. But it's a tantalizing target for lawmakers, raising the potential to raise hundreds of billions in revenue without needing to raise taxes at all.

The question is how big the tax gap really is — and how much it can realistically be closed.

The Internal Revenue Service has estimated the tax gap is $440 billion per year. But IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig stunned his audience at a recent Senate hearing when he offered a new number: about $1 trillion annually.

The old estimates don’t take into account the recent boom in income made by self-employed “gig” workers, which can be underreported, concealed offshore income and the rising use of cryptocurrency, which makes it hard for the IRS to identify taxpayers in third-party transactions, experts say.

The $1 trillion figure “is not crazy. That’s totally possible,” says Steve Wamhoff, director of federal tax policy at the left-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

But Sen. Mike Crapo of Idaho, the senior Republican on the Senate Finance Committee, called it “speculation.” And he's worried it could push the IRS toward overzealous enforcement.

“It would be detrimental if IRS efforts do not strike the appropriate balance between taxpayer responsibilities and taxpayer rights,” Crapo told Rettig in a letter this week.

The IRS has been on the losing end of congressional funding fights in recent years, taking a cut of about 20% since 2010, adjusting for inflation, even as its responsibilities have grown. Biden’s new spending proposals include an extra $80 billion over 10 years to bolster IRS audits of upper-income individuals and corporations.

But some experts say bolstered audits could fall far short of a $700 billion windfall. The Penn Wharton Budget Model, a research organization associated with the University of Pennsylvania, projects the proposed spending on IRS collection efforts would bring in about $480 billion from 2022 to 2031.

In selling its plan, the White House has emphasized what it describes as fixing a “two-tiered system of tax administration” in the U.S. While regular workers pay taxes on the wages they earn, some wealthy taxpayers find ways to maneuver around them.

Those with annual incomes under $25,000 are audited at a higher rate (0.69%) than those with incomes up to $500,000 (0.53%), according to IRS data. Taxpayers who receive the earned-income tax credit, which applies mainly to low-income workers with children, are audited at a higher rate than all but the very wealthiest filers. The audit rate for millionaires plunged from 8.4% in 2010 to 2.4% in 2019.

The IRS rejects the notion of unfair audit treatment, saying that critics have misinterpreted the data. Rettig bristled at the suggestion at the Senate hearing. High-income taxpayers “are audited more than any other taxpayer,” he said, at a rate over 8% for those earning more than $10 million.

So far, Republicans are only ruling out revisiting the 2017 tax cuts that they passed without any Democratic support. How much they are willing to boost the IRS as part of an infrastructure bill remains to be seen. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky said Republicans would rather finance infrastructure through user fees such as tolls and gasoline taxes.

But after pushing the agency's steep budget cuts over the past decade, it would be a remarkable shift for the GOP to back the kind of sustained investment in the IRS that Biden is talking about — and that experts say is necessary to narrow the tax gap.

Republican lawmakers with control over funding for the IRS have long accused it of overreaching into ordinary taxpayers’ lives. Their hostility toward the IRS exploded into outrage in 2013 during the Obama administration, when the agency admitted having targeted conservative tea party groups with heightened, often burdensome scrutiny when they applied for tax-exempt status.

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, wrote in his home state newspaper, the Des Moines Register, that he’s not opposed to closing the tax gap, but he has concerns about the scope of the White House’s efforts.

“Instead of promising a chicken in every pot, Biden’s plan promises an auditor at every kitchen table,” Grassley wrote.