JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — The phone in Miss America’s hotel suite rang and rang that morning, but the 21-year-old beauty stayed in bed. It could wait.

She figured it was the operator with a wake-up call, and after a big Gator Bowl game the day before, she wanted to sleep as long as she could.

Then she heard sirens. Then she smelled smoke.

There would be no more sleeping in, not at the Roosevelt Hotel that morning.

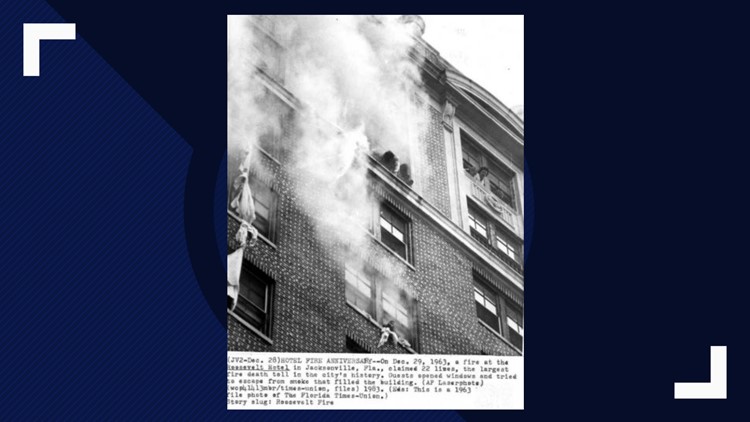

On Dec. 29, 1963, a fire broke out in the ballroom of the 13-story Roosevelt, one of downtown Jacksonville’s most grand hotels, on Adams Street just west of Main.

The blaze never made it above the second floor, and no one ever figured out what caused it. But smoke and toxic fumes rushed up air shafts, choked hotel hallways and crept under doorways.

They were killers.

In the minutes to follow, hotel guests died in their beds, unable to draw breath. A woman plunged to her death in a desperate effort to escape her room on knotted-together bedsheets. Assistant Fire Chief James R. Romedy, 49, was among the firefighters who charged headlong into the smoke and worked their way up as far as the roof; he collapsed and died of a heart attack while rescuing guests on an upper floor.

OUT THE WINDOW

Owen Duncan of Pageland, S.C., was using his electric razor in the bathroom of his 12th-floor room when he saw smoke pouring from the electrical outlet. He rushed to the hotel hallway, but black, acrid smoke turned him back. So he tied his wife to a blanket and lowered her to the window below, where two guests in that room hauled her in.

He followed, and soon all four of them swung down yet another floor lower, looking for someplace safer.

In the black smoke on the sixth floor, University of Florida basketball player Tom Baxley was separated from his teammates. Somehow, in the confusion, he ended up one flight higher, huddled in a room with strangers, a married couple.

He was struck by something odd: The husband and wife were nervous and, while waiting for firefighters, sitting there in the smoke, they lit up cigarettes and puffed away.

‘A FINE BUNCH’

Though firefighters’ ladders wouldn’t reach high enough for all guests, that didn’t stop Jimmy Dukes. The enterprising firefighter climbed up one of the 100-foot ladders, carrying another ladder with him, and put the two together.

Several people were able to scurry down the double ladders to safety.

“Talk about daring,” said Battalion Chief Miles Bowers, now 87 and retired nine years. “Everybody thought he was crazy, but it worked.”

Though Frank C. Kelly had retired as fire chief, he had been one of the first at the hotel after the alarms. He watched the men working, charging into the smoke, climbing all the way to the roof.

Hard to argue with that.

UP ON THE ROOF

Lt. Ural King’s helicopter bounced and bucked in the updraft created by waves of heat rising off the Roosevelt. He hovered just a few feet above the roof, worried it wouldn’t bear the weight of his copter if he touched down.

Mayor Haydon Burns had pleaded with the Navy to help, placing a call to Cecil Field at 8:15 a.m. Five minutes later, helicopters were in the air, from Cecil, from Jacksonville Naval Air Station and from Mayport.

King made four trips between the roof and a parking lot where ambulances waited. On top of the hotel, firefighters passed victims up to his helicopter. The first was unconscious. The last - Assistant Chief Romedy - was dead.

It was, King said later that day, “the hairiest spot I’d ever been in.”

Moon wasn’t hurt, but there were emotional scars: After the Roosevelt, while traveling extensively for AT&T, he insisted on first- or second-floor hotel rooms. And he always mapped out an escape route. Just in case.

A HERO IN THE SMOKE

A 19-year-old hero, just out of the Navy, gained the distinction of saving Miss America. Bill Fielden, the son of a Miami public-relations man traveling with the beauty queen’s entourage, stumbled into her room and threw a wet towel over her head.

They sat tight and were eventually led out by firefighters. Axum, wearing a beaver coat, pajamas and slippers, salvaged just two pocketbooks and her Miss America crown.

Seven hours later, at a news conference at Baptist Memorial Hospital, Miss America told her harrowing story. She wore a white hospital gown and a plastic identification bracelet. She smiled as Fielden, her rescuer, leaned over and planted a kiss on her right cheek. She looked no worse for wear, and soon went to her next stop: Miami, and the Orange Bowl Parade on New Year’s Day.

But the Roosevelt Hotel was not yet through with Miss America. On New Year’s Eve, Miami doctors confined her to bed and ruled her out of all Orange Bowl activities. She had burns in her throat and nose. She still had to heal.

She is now Donna Axum Whitworth, 71, living in Fort Worth, Texas. She said that wherever she traveled as Miss America 1964, sounds of fire trucks outside her window left her shaking and petrified.

It took a long time for that morning at the Roosevelt to leave her.

“It will forever leave an indelible print on my mind,” she said.

Times-Union writer Sandy Strickland contributed to this report.