ST. AUGUSTINE, Fla. — Just an hour after sunrise, about a dozen archaeologists and archaeology students pack into small boats, bound for a place few people ever set foot on now.

"In the mornings when we get to the site, when the sun has just come up, you just feel like," Dr. Lori Lee pauses and sighs, "we have arrived in this very special place."

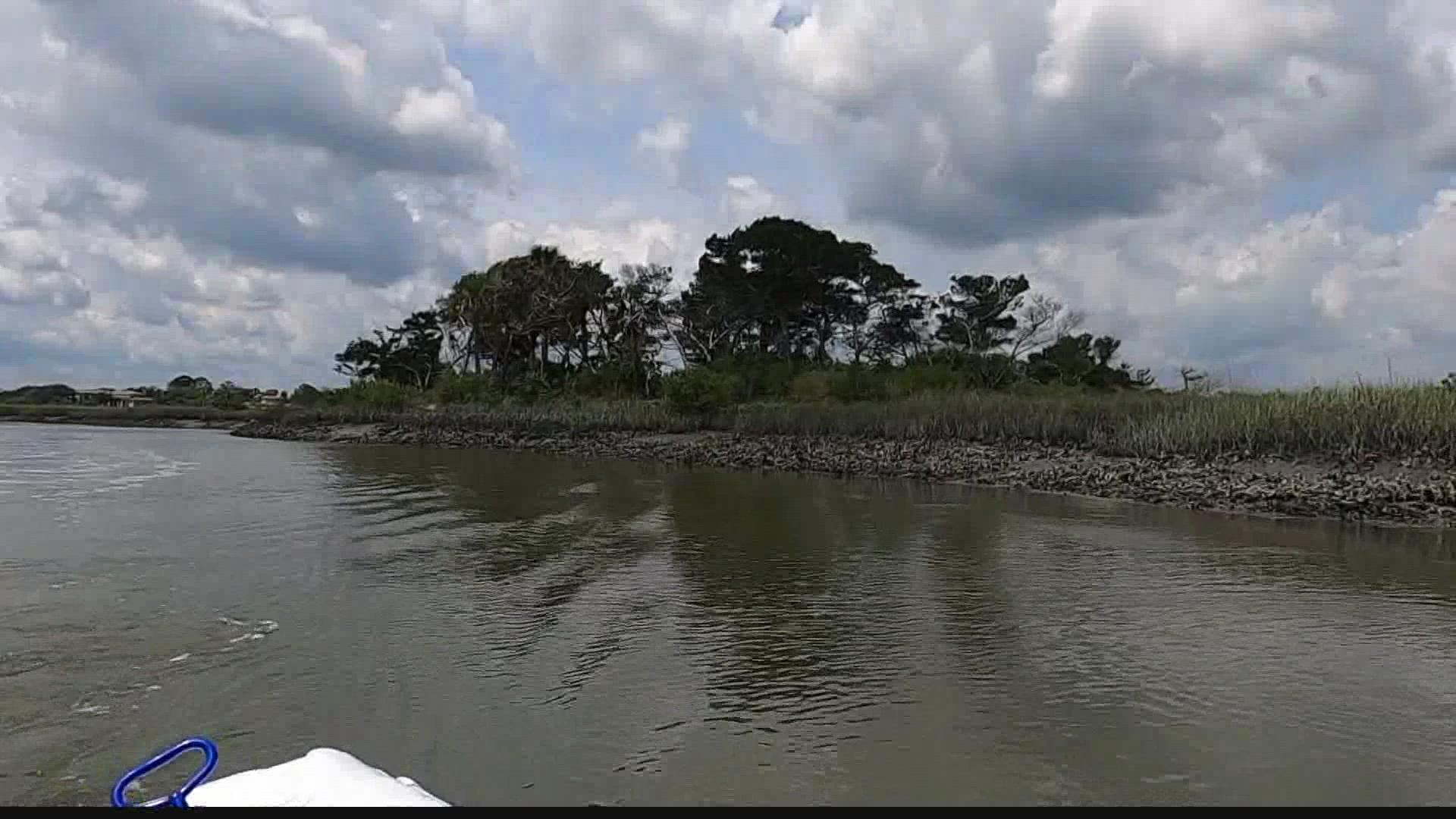

That place is part of the Fort Mose State Park property in St. Augustine along Robinson Creek.

It is only reachable by boat.

And for six weeks, this is where archaeologists and students from around the country are sifting through layers of history to "find out more about the lives of the people who live and worked at Fort Mose," Lee said. She is an archaeologist and a professor at Flagler College.

Fort Mose used to stand on this land the 1700’s. It was a place where Africans – who fled their enslavement in the Carolinas -- found freedom. Here, they were working and living in colonial Spanish Florida.

Fort Mose is two miles north of the Castillo de San Marcos, the fort in modern-day downtown St. Augustine.

And this dig is rare.

Not only are archaeologists digging in the dirt, they are also digging underwater just off the shore at the same time, on the same project. Sometimes the divers are in just a few feet of water.

A crew from the St. Augustine Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP) is conducting the marine portion of the project. Archaeologist Chuck Meide leads LAMP and explained, "The creeks that once fronted this piece of land have now eroded into where the fort used to be."

In the 1980’s, archaeologists determined that Fort Mose stood on what is now an island. But to the untrained eye, there's nothing there that looks like a fort. So what happened to it?

"It wasn’t constructed out of stone," Dr. Mary Elizabeth "Liz" Ibarrola of the University of Texas - Austin noted. "It was constructed out of dirt, primarily. The fort went back into the ground over time."

The creek floor and the freshly-dug archaeological rectangular holes on the island are releasing everyday items from the past: Native American pottery, European dishes such as a white tea cup, a flint to a musket or pistol, and lots of animal bones and oyster shells.

Ibarrola pointed to the bone and said, "That tells us what people are eating."

"We definitely are digging on a site that is under the gun," Dr. James Davidson, Associate Professor at the University of Florida said, as he ran a trowel along a flat path of dirt.

"It's projected that in 30 – 50 years, we’ll have a one to three foot rise of sea level and high tide even more. The highest part on this island is only 5 feet. So we will lose 70 - 80 percent of the fort in 30 - 40 years. If we want to know it in a way beyond a history book, we have to dig now."

Ibarrola said, "It’s a story of self determination, freedom, and people making due."

And every little artifact reveals a little more about this story… on a tucked away, eroding island.