JACKSONVILLE, Fla — Dozens of property owners are looking to the city for collaboration to find a solution to the decades-old infrastructure problem that continues to plague their Jacksonville neighborhood.

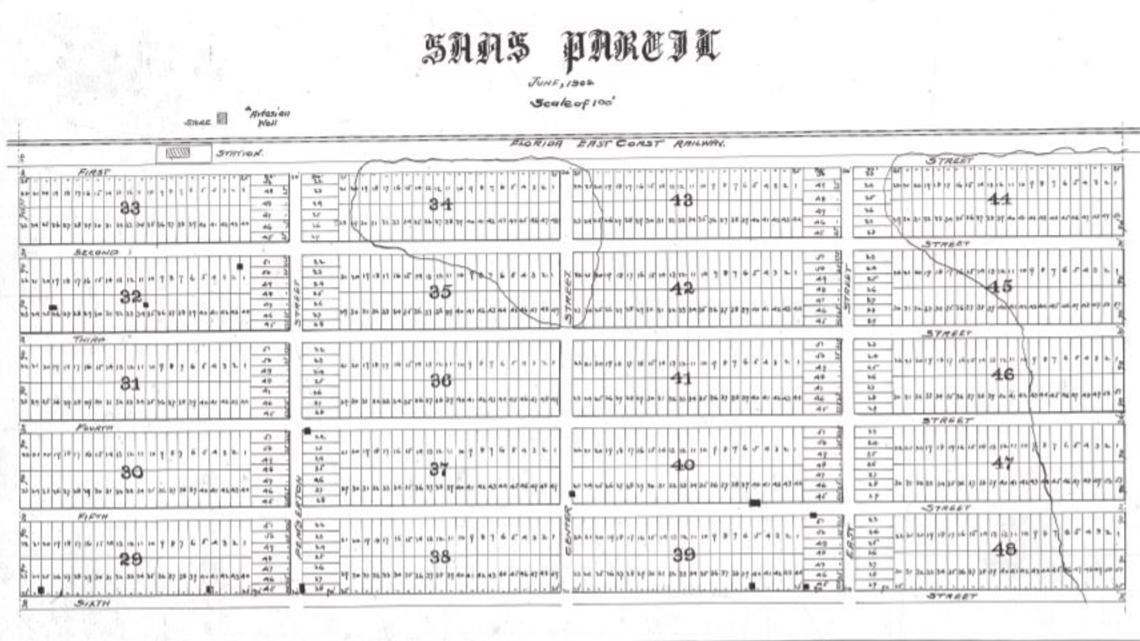

Tucked off Beach Boulevard, houses in the Sans Pareil/Pemberton area sit off dirt roads. It's a uniquely rural feel in a rapidly developing part of the city.

But there's one aspect of the neighborhood that's impossible to ignore.

"We lose bumpers, front ends," said John Bennett as he navigated a plethora of potholes on Sans Pareil Street. "People are struggling."

Potholes, from small to large but often deep, are hard to miss. During the rainy season, flooding becomes a major concern for residents.

"The holes are so bad," said Heather Correia, a 16-year resident. "You can't drive on the right side of the road anymore because you're literally zig-zagging, swerving."

Gathering in a church parking lot Monday afternoon, Correia, Bennett and a group of other property owners met to discuss the issues in their neighborhood and speak to First Coast News.

Kevin Ingwersen and his wife Jennifer Wesely moved to Sans Pareil from the coast after purchasing property.

"Everybody looks out for each other, the neighbors are nice," Ingwersen said. "But the roads are the one thing I can say we don't like about the place.

Many roads in Sans Pareil/Pemberton are difficult or even impossible to drive on without a 4x4 after rain events, and residents say water can pool for days or weeks without drying up.

The difficulty in the maintenance of the roads lies in their classification.

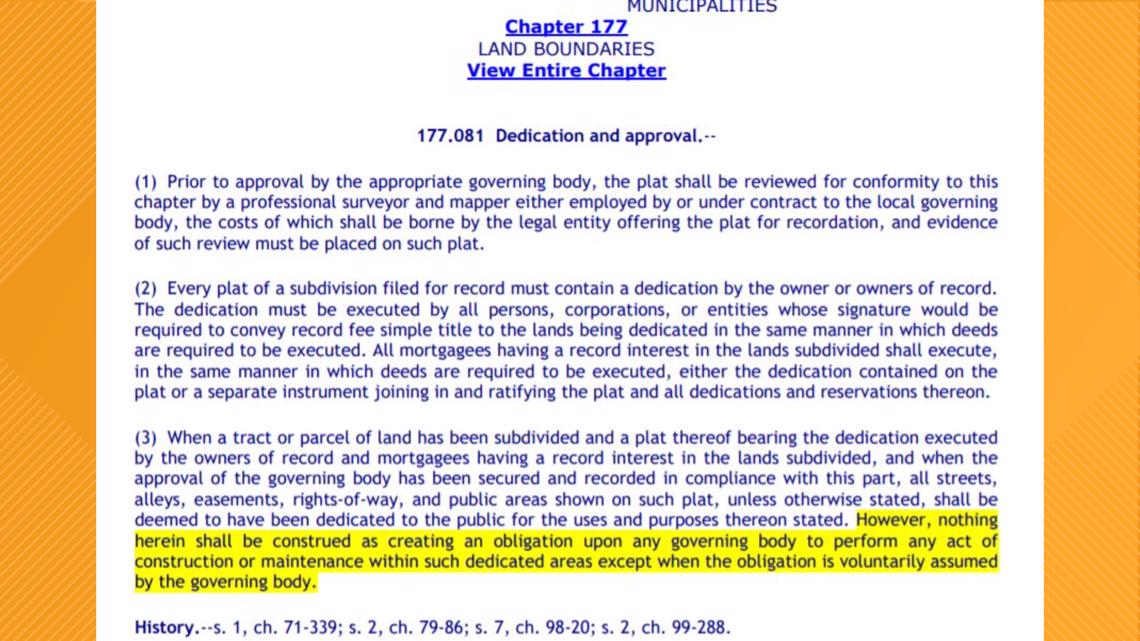

While signs at the entrance of the neighborhood note "Private Road," the roads are classified by the city as "Public Right-of-Ways," meaning property owners also own the sections of road bordering their land.

"The owners abutting that easement have the responsibility for maintaining the roads," said Councilman Danny Becton, who represents the area.

Becton said the neighborhood was originally platted in 1909, and that since then maintenance of the roads was never transferred to the city and property owners kept their easements.

Residents who spoke with First Coast News said they prefer the dirt roads, but also feel the area has outgrown the manner of maintaining the roads and the lacking drainage.

"With other neighborhoods being built up around us, we're getting more and more water in ours," Wesely said. "We have to be able to have proper drainage."

First Coast News spoke with Becton about a litany of concerns expressed by neighbors, including access for emergency services. Some residents said they worry that, in an emergency, responders would not be able to get to parts of the neighborhood in time.

"I have cared deeply of trying to find a resolution for this neighborhood from day one," he said. "It's because those are always possibilities. There's a lot of things that homeowners can do to delay emergency services, and certainly not maintaining the roadways, these public right-of-ways within Sans Pareil and Pemberton, add to that."

A spokesperson for the Jacksonville Fire and Rescue Department said the crews tasked with covering the area are familiar with the obstacles and know what to expect, including following rain events.

But ultimately, Becton said, it comes back to the issue of the easements. He said the property owner, in charge of the maintenance of the easement, is ultimately responsible for keeping their portion of the road clear.

Becton said he asked the city's Municipal Code Compliance Division (MCCD) whether it would be possible to enforce the maintenance of easements through citations to property owners.

The answer? No.

It turns out, there's no city ordinance relevant to the situation for the city to cite. Plus, MCCD can only cite on private property, and the city said: "Public Right-of-Ways" are not technically private roads. In Jacksonville, private roads are defined as, "a privately owned or controlled and maintained drive, street, road, lane, not accepted by the City of Jacksonville as a public road."

"It costs too much money for us to do it ourselves," Correia said. "And it's gotten worse and worse through the years that I've been here. It literally impacts everyone in the neighborhood."

And the city also tied drainage systems to the roadways, saying the stormwater system is part of “official transfer or acceptance” of roadways by the city for maintenance.

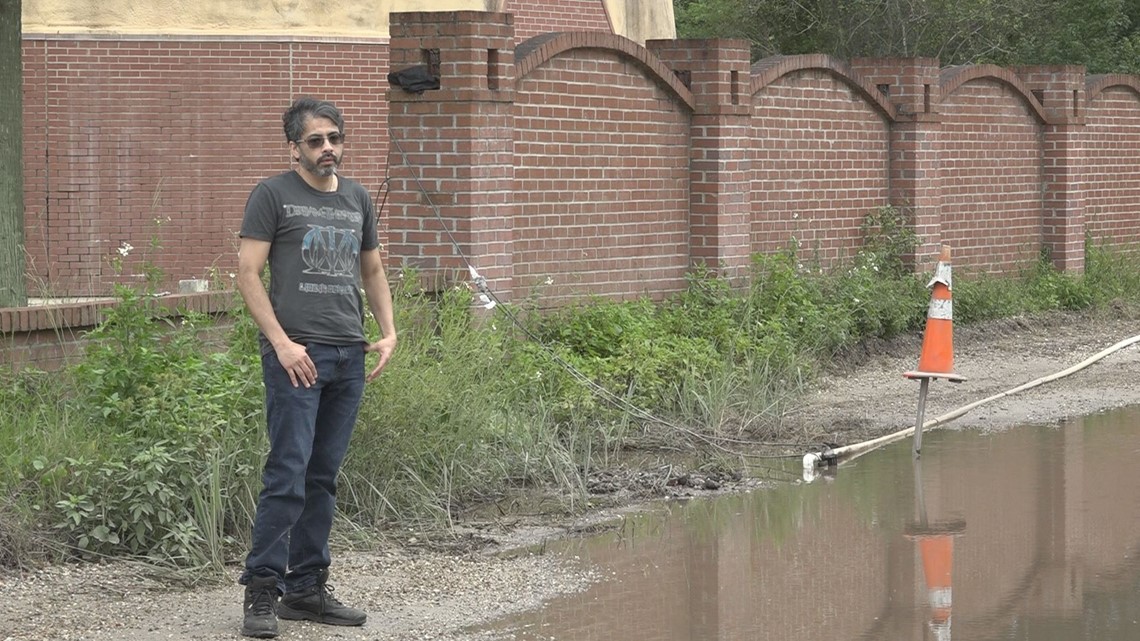

Without the help of ditches or culverts, residents like Dan Laski have found their own unique ways to drain their portions of the road.

Laski estimates he's spent around $12,000 over the past six to seven years, between filling in holes with aggregate and constructing a makeshift pumping system.

"And that doesn't include the amount of money that it costs to pay for the electricity of the pump and my own labor," Laski said. "When this is fully flooded, there's no way that someone in a normal, everyday car is going to be able to make it through here. I have to maintain it for everybody that comes through here, and I also have to try to make sure that people can make it in and out safely."

But like other residents, Laski is looking for a long-term solution. He said traffic, especially from trucks going to nearby construction sites, means fixes are only ever temporary.

A number of plots toward the back of the neighborhood have been developed in recent years, which residents said they believe is worsening flooding issues.

Becton said property owners are allowed "to drain into the right-of-way," but that it is possible for the city to have a property owner make corrections if other properties have been negatively impacted.

"The problem the city has is they can't quantify the adverse effects," he added, saying it's difficult to measure increased flooding over years prior and to attribute it to one specific property owner.

Ultimately, neighbors said they are looking to collaborate with the city on solutions.

Becton said solutions could include the city maintaining the roads by assessing impacted property owners (which would require legislation to be passed or 60 percent neighborhood approval), or the formation of a special taxing district and governing body that could borrow money for improvements to pay back over a longer period of time.

In the short-term, the coming winter months will provide some reprieve for long-flooded roads in the area, until the cycle starts back next year.

"I filled this in four times right here," said Bennett, pointing to a large pit filled with water. "Four times."

"If people can't go to work, they can't pay their bills," said Bennett, as he detailed the work he had done on the roads on his own time. "Everybody can't afford it, and it's getting worse."