JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — It takes a rare degree of empathy to go above and beyond to help people like Maxine Engram has.

During a recent visit, more than one person at Sulzbacher Center for the Homeless in Jacksonville used the exact same phrase to describe Engram to First Coast News: "one of a kind."

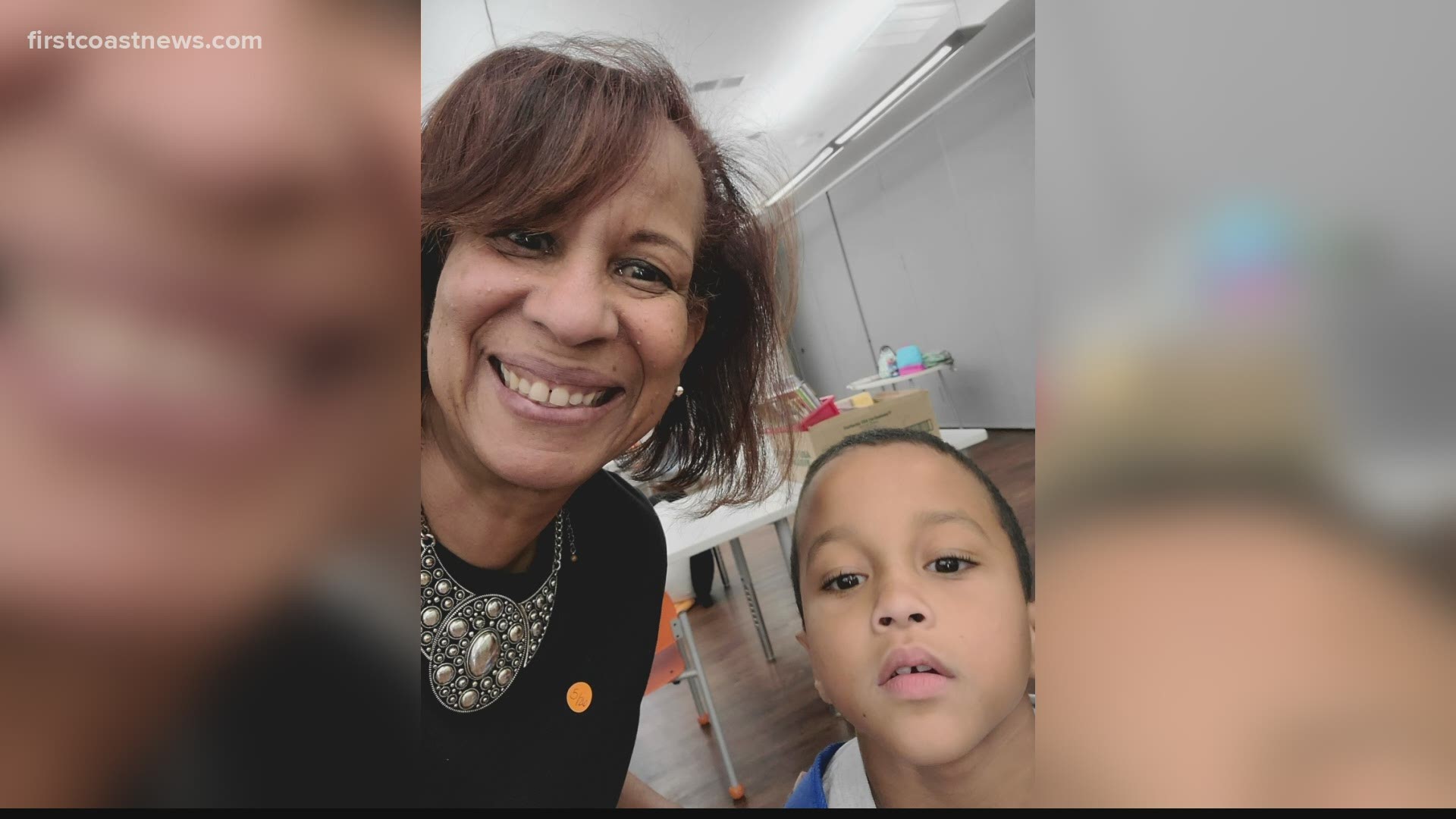

Engram herself estimates that she worked with at least one thousand kids at the center in her roughly 13 years at Sulzbacher, where she didn't just manage the children's program but created it.

"It was more of a kind of recreational, enrichment-type activities. And then she added a whole other educational component," Chief Program Officer Brian Snow recalled of Engram's first days and months. It didn't hurt that Engram, certified in general education and special needs, was coming off a lengthy career with Duval County Public Schools, first as a sixth-grade teacher and then as an administrator, making sure certain special needs children qualified for federal programs.

"The children were pretty much just kind of running around," Engram said of the situation at Sulzbacher when she arrived. "So I mentioned to someone standing on the sideline that, 'I promise you it won’t be like that next year'."

Bit by bit, Engram developed a comprehensive program, one she knew would require improvements to children's grades and esteem concurrently.

"I found myself really, really caring and being committed to all of the children. I think that’s what won them over, because I was just as excited as they were, to see them succeed," Engram said.

That included building what she called the "Wow Wall," a place where children's accomplishments could be posted for everyone to see, including those pulling their grades up.

"Any kind of accolades that the children got, all of that was posted on the Wow Wall," Engram described.

Engram soon knew she had to be all-in, even if it meant shaping her life around the needs of others. "You have to be here all the time, and the kids can trust you to be here."

Engram knew she had to be disciplined about her own well-being in order to consistently help others.

"I made certain that I tried to not ever get sick so I could be here for every tutoring evening. Every night that I had to be responsible for the children, I wanted to make certain I was here."

However, it went far beyond scholastics. Engram thought nothing of being at the center by 5:30 a.m. on Christmas mornings, to see the children wake up. She also knew it would mean taking children beyond the walls of Sulzbacher. One of many examples was taking kids on field trips to learn how other cultures celebrate holidays. She also recalled a specific memory, when she took a group of children to the circus, where they had the rare privilege of watching from a private suite.

"And there was one teenager that said ‘I’m going to stay in this room because I may not ever see this again.’ And it just did something to me to see how he appreciated that opportunity," Engram said.

Of course, Engram's job, which she essentially created and defined as she went along, required boosting the confidence of the children's parents who themselves typically were in difficult circumstances.

"She’s someone that I could confide in," said current Sulzbacher resident Glenda Mitchell, mother of a 13-year-old daughter who has stayed at the center with her. "When we came to her we were, like, low self-esteem, no vision, no hope."

"I didn't have a clue what to do or where to turn she was able to direct us to a more stable place," Mitchell continued. Speaking of the building relationship between her daughter and Engram, Mitchell said "[My daughter is] 13 and she had never mentioned a bond to me before."

Engram is no stranger to fear herself as she began developing empathy at an early age. She was one out of a group of ten African American students first brought to integrate Ribault High School in 1967.

"My worst day was the day that they threw eggs on me in the cafeteria," she said. "Sometimes I wonder, even now, what made me get up and go the next day and the next day, and we graduated from there."

But homeless families and children haven't been Engram's only beneficiaries. Before retiring in September, she voluntarily began looking after the children of her colleagues as the coronavirus pandemic began sweeping the country, enabling those colleagues to continue focusing on helping the homeless while their own children were displaced from school and needing supervision.

"She has been a tremendous example and a mentor, not only for the parents who live here but also for the staff," Snow said, adding that Engram always leads by example.

"A woman of integrity and prides herself – and I’ve seen this consistently – that you can be a single woman and be very contented."

Engram's a woman whose effectiveness could ironically be measured by how she elevated people to not need her help anymore. "Maxine has done that very well," Snow said. "I’ve seen many folks through the years kind of upset and hugging and crying when they leave."

Engram is retired now, however when you're talking about a woman who devoted so much of herself beyond any official job description her colleagues say she'll never be far away.