JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Achieving racial equity requires difficult conversations, and acknowledging the systemic racism that has shaped the communities in which we live.

As part of our series "Legacy of the Redline," First Coast News sat down with Ennis Davis, a renowned local urban planner with nearly two decades of experience studying and working in the field.

Davis has extensive knowledge of the history of development in Jacksonville and how that development has impacted the city's Black neighborhoods.

"Every single block, every single building, every single site has a story if we’re willing to listen and look for it," Davis said. "Understanding zoning and history, the development of the city, the policies we have in place and how they play out over the course of time, that can be a very significant and important tool."

For years, Jacksonville's oldest neighborhoods (many historically Black communities) have lagged behind newer and more affluent areas incorporated into the city during consolidation.

Baked into the city's zoning history, going back to the Jim Crow era, is a pattern of discriminatory policies that pushed development away from majority Black neighborhoods and into white parts of town.

"And that kind of set the foundation for what neighborhoods will be 'redlined' in the following decades," Davis said.

Jacksonville has a deep Black history spanning generations, with its own unique culture derived from Gullah Geechee communities. The Gullah are a federally-recognized group descended of formerly enslaved Black people living along the Southeast Atlantic coast, sharing common traditions.

"Jacksonville has the largest concentration of Gullah Geechee descendants in the U.S. So it's got a very unique history to it, that you can't find outside of this region," Davis said. If you look at our street grid today, you notice it kind of curves along the river. A lot of our street grids and plats are original land grants and plantations that were in existence before Jacksonville."

Other aspects of visible Gullah culture in Jacksonville include shotgun homes, which Davis said is a style referred to as the "Southern man's row house" and food like shrimp and grits and barbecue.

Understanding where many of the racial disparities in the city come from means going back decades, Davis said.

Soldiers in Black regiments of Union forces following the Civil War begin to settle in Jacksonville, which at the time was confined to the north bank of the St. Johns River.

Over the course of years, historically Black neighborhoods like Lavilla begin to develop. Following the Great Fire of 1901, Davis said Jacksonville becomes known as the "Magic City," and becomes a hub for Black people in the South.

"If you are Black in a rural area, this is where everybody wants to come to find jobs, economic opportunity," he said.

But as the city grew, the Black population was confined to certain neighborhoods, like Lavilla, Brooklyn and the Eastside. Other parts of the city, like Downtown, Springfield and Brentwood, developed as white neighborhoods.

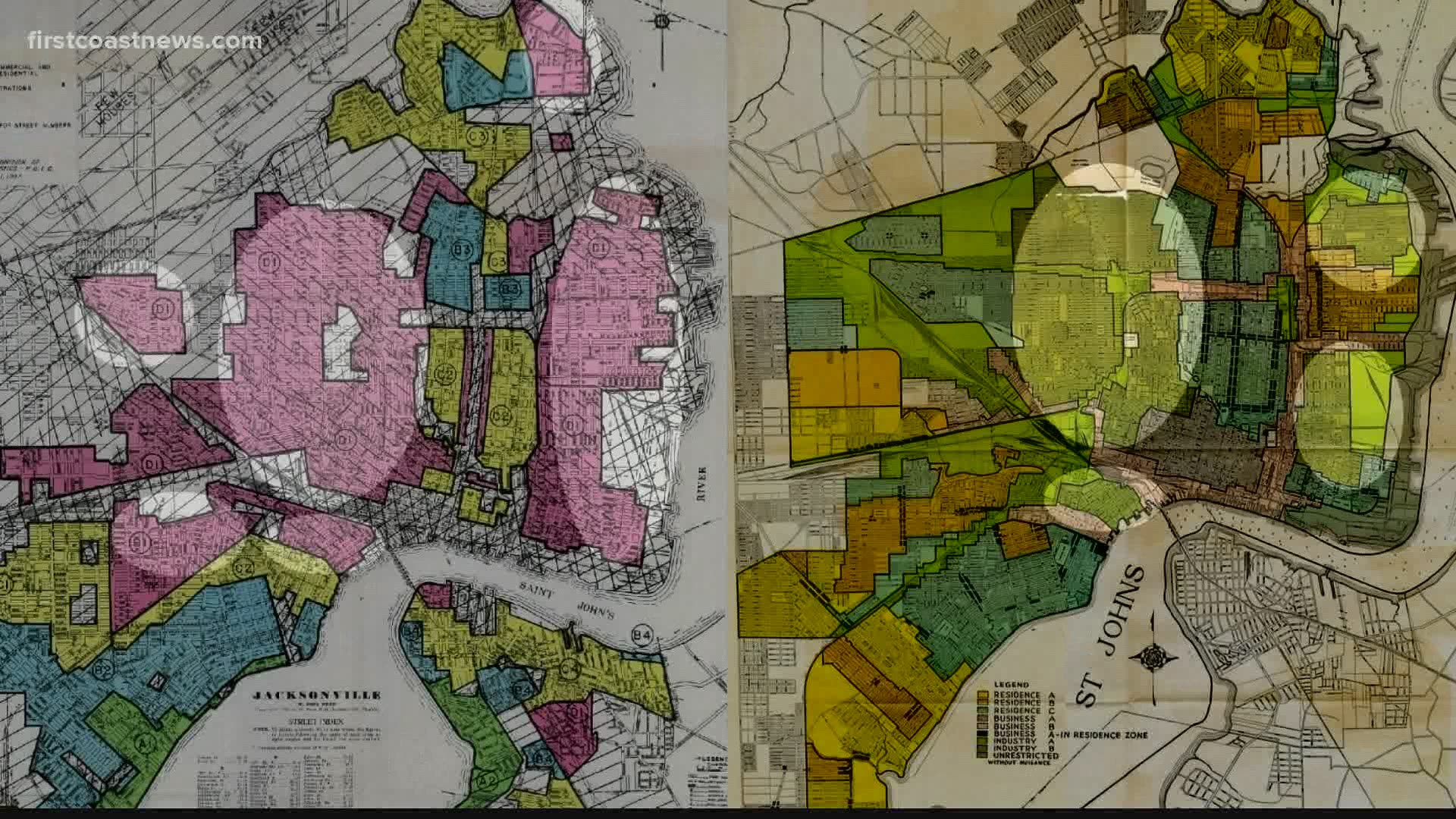

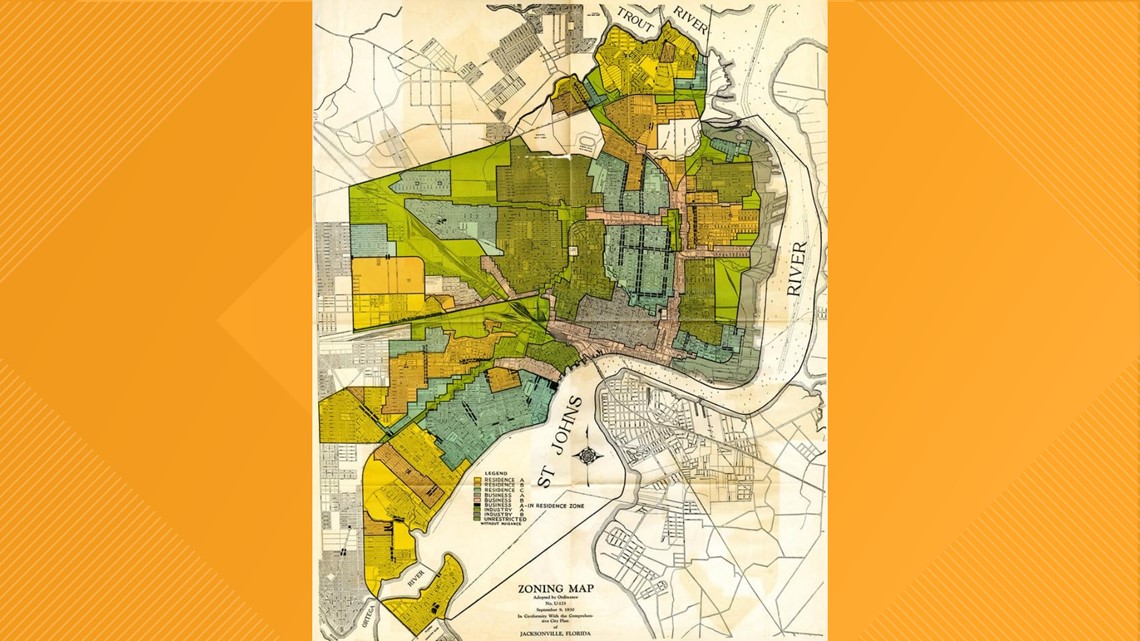

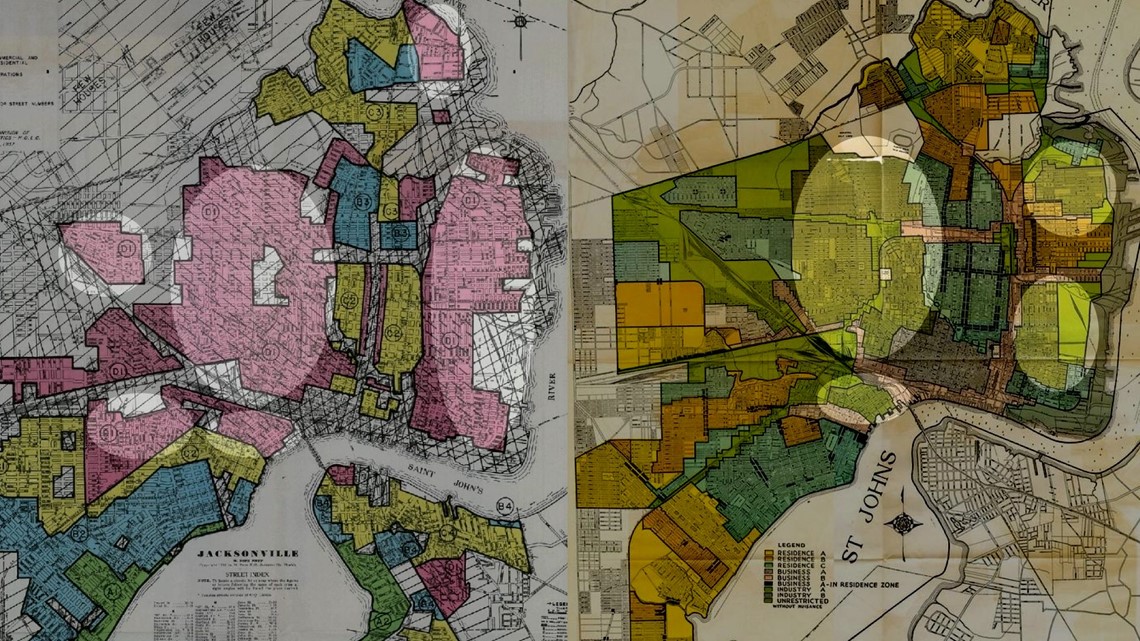

Then, in the 1920s, Jacksonville became the first city in Florida to develop a zoning map as part of its comprehensive plan.

"That zoning code is largely race-based," Davis said. "By that time, racial zoning had been made illegal. But 'Euclidean zoning' or exclusionary zoning was a way around that."

Davis said the code, which classified the city's Black neighborhoods as "unrestricted," allowed for a wide range of land usage within those areas that would not be allowed in white neighborhoods like Riverside.

"You could put your foundry next to somebody's house, or you could open up a slaughterhouse next to somebody’s house," he said. "So all the negative things that the city’s leaders at that point did not want to see in white neighborhoods such as Ortega or Riverside or Murray Hill. Those things weren't allowed there."

Because of the zoning, industry was pushed into Black neighborhoods.

"So today, you'll find these old industrial sites, you'll find contaminated sites, you'll find that more in those Black neighborhoods today than you will in Riverside," Davis said.

"There's a reason that certain neighborhoods look like they look today. And that kind of set the foundation for what neighborhoods will be redlined in the following decades."

On the map below, the dark green areas are zoned as "unrestricted."

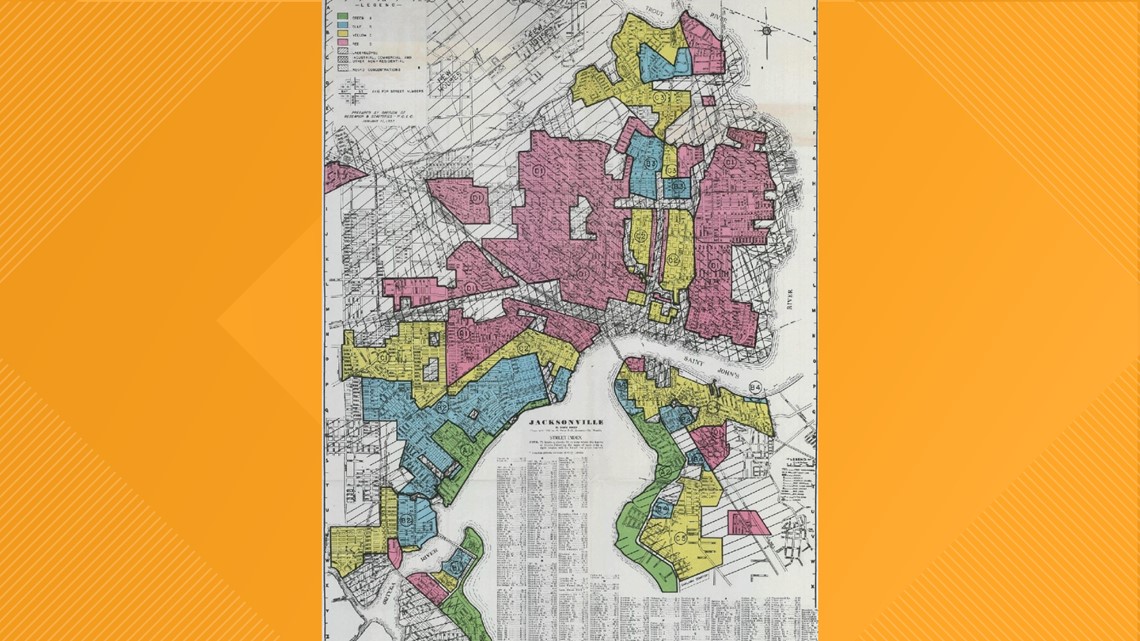

The concept of "redlining" was a racist practice used mostly by government agencies to deny services, like mortgages, in majority Black inner-city neighborhoods.

Outlawed through a series of laws in the latter half of the 20th century, redlining as a practice made Black homeownership difficult by targeting certain communities as being too risky to invest in.

"If it was deemed to be a neighborhood where they did not want to encourage investment, it was considered hazardous and colored red on the map," Davis said. "Essentially, across the U.S., not just Jacksonville, every majority-Black neighborhood in a city at that point in time became red."

After the passage of the G.I. Bill, in which returning WWII veterans were able to receive low-interest mortgage rates, "white flight" to suburbs began, leading to the growth of areas like Arlington, Davis said.

In Jacksonville, the 1957 "redlined" map of the city matches closely with the "unrestricted" zoning areas in the city's first zoning map.

"Through systematic, discriminatory public policies and investments, you've limited economic growth and opportunity in certain areas of the community, to encourage it in other areas," Davis noted. "So those who have the access to go to these other areas or to invest in these other areas, as time goes on, you see generational wealth grow within those families in those communities."

"If you are from a family that didn't have that access, and you were forced to be on the other side of town, you don't have that generational wealth, which is where you get the wealth gap from."

And as time goes on, other factors that impact Black neighborhoods in Jacksonville come into play, Davis said. For example, the establishment of the Interstate Highway System is used as a method of "urban renewal" by eliminating blight, Davis said. But the "blight" was often deemed to be Black areas of town.

"The blight is typically deemed those areas that have been redlined," he said. "They never got the investment to build infrastructure or build the economic life, wealth of the people who live in those areas. Now areas where the property is taken via eminent domain, so you're not even getting paid the worth of what the property is."

Davis said the construction of I-95 cut through a swath of Jacksonville's Black communities, impacting places like Lavilla and transforming how the city looked at public policy and development.

Lavilla was the site of the first documented performance of the blues, and the birth site of the famed James Weldon Johnson, who composed "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing" with his brother.

Today, the once-bustling Black neighborhood is mostly a collection of empty fields in the shadow of Downtown Jacksonville.

"The buildings didn't have the same historic designations or protections that allow for the redevelopment opportunities you'll find in Riverside, Springfield and the core Downtown today," Davis said.

Ultimately, it comes down to understanding and being aware of the history of racial discrimination and how the impacts are still felt today.

"If I put a coal plant next to your house, and then I took your neighbor and moved them across the river, and I put a park next to their house and didn't allow any type of industry, over the course of 20 years of living there, who do you think would have a healthier lifestyle?" Davis asked.

"If you take away the educational values and resources, if you take away the economic fabric of these neighborhoods, you end up in a position where you don't have a lot of job creation," he said. "You have an educational system that may not train the people growing up within these neighborhoods to even be qualified for the jobs that are here."

Today, First Coast News continues to dig into Jacksonville's past in hopes of forging a better future. And it starts with being aware and engaged.

"As we try to tackle issues within our community, we have to keep that in mind that history plays a role in how we got to where we are today," Davis said. "You can put as much money as you want to into a result. But if you don't change the cause, you're not going to alleviate or resolve the issue."