Monday marks the 106th anniversary of the birth of Rosa Parks, who in 1955 refused a Montgomery, Ala., bus driver’s order to move to the back of the bus and give up her seat in the whites-only section. Parks was arrested, which sparked a boycott of the Montgomery bus system and made her a powerful symbol of the struggle for equality.

On one of Mark Kerrin’s first mornings as bodyguard to Rosa Parks, she brought him some orange juice. A simple gesture, perhaps. But it struck him, that day in 1994: “This was so historic to me — the mother of the civil rights movement, bringing a glass of orange juice for me,” he said.

That wasn’t the end of it though. She knew he was a Southerner, so she had made him a breakfast of eggs, grits and sausages, just as a Southerner would like.

What he didn’t know yet about her was that she was a vegetarian. That’s something he discovered with his first bite of meatless sausage. He managed to choke it down. Barely.

She just kind of smiled, he said — a smile that soon became familiar to him.

Kerrin, who is 65, graduated from New Stanton High School in Jacksonville and became a police officer in Atlanta and Jacksonville. He later taught college courses in criminal justice and information technology, was an electronic surveillance expert and owned a security consulting business.

In 1994 he volunteered to install a security system in Parks’ home in Detroit after she was attacked there by a young man demanding money.

That eventually led to him becoming a bodyguard for Parks for the next few years, during which he made frequent trips from his home in Jacksonville to wherever she was traveling next, from Florida to Alaska.

He wore a bulletproof vest and was heavily armed in this duties, for which he volunteered. “I told them, I can’t charge Rosa Parks,” he said. Eventually, the Rosa and Raymond Parks Foundation ended up paying his expenses for travel.

They became friends, and often sneaked away from official events; she liked to walk and go to parks. He even took her fishing. He documented much her life — and the memorial services after her death — with a camera he carried everywhere.

Kerrin always called her Mrs. Parks, out of respect, and would correct President Bill Clinton when he called her Rosa. He did that so often it became a running joke between the president and the bodyguard.

Parks had moved to Detroit following her arrest after she and her husband lost their jobs and faced death threats in Alabama.

She lived simply there, in a modest apartment. “A bank account full of nickles and a basement full of plaques,” Kerrin said.

She sometimes spoke to him of that day in Montgomery in 1955, describing it as a breaking point. “She said she was just tired of the humiliation and the injustice that had happened,” he said, “so she refused.”

She died at 92 in 2005, after which she became the first women to lie in honor in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C. Ceremonies also marked her passing in Detroit — where a young politician named Barack Obama was among those who spoke — and in Montgomery.

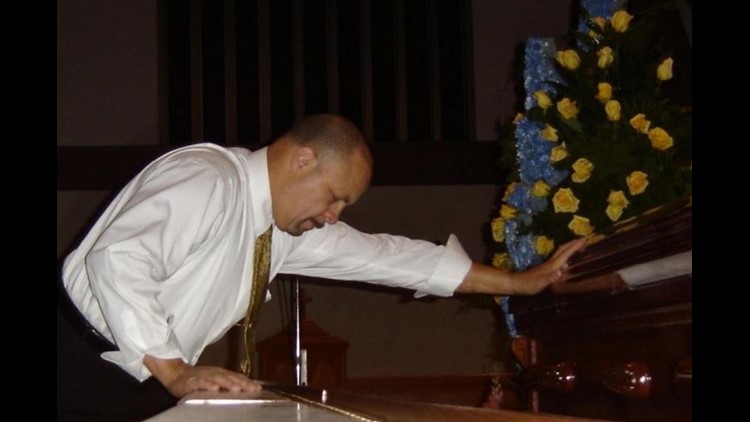

Kerrin was there for each event, guarding her coffin: His work, he says, was not yet done.

As a former police officer, he stresses how revered Parks was by police officers, of all races, across the country.

That’s reflected in the photos he took of her life and her funeral services, which often feature law enforcement officers. He’s donated them to the National Law Enforcement Museum in Washington and has also given photos to the Library of Congress.

Working with Parks and doing security work for the Atlanta police department gave him the chance to interact often with the mighty and the rich.

“I have never been impressed by any celebrity, any president,” he said. “Only her. She would speak to you the same way she would speak with presidents.”

Matt Soergel: (904) 359-4082