JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Jacksonville is struggling with the plans for a Confederate monument in a city park.

City council members are divided about removing the monument to a different location. It looks like the city council is leaning toward keeping it in place, despite protests to take it down.

However, the actual history of the monument is one not many know.

"It’s a little different than most," Dr. William Lees said. He co-wrote the book about Confederate monuments in Florida, "Recalling Deeds Immortal."

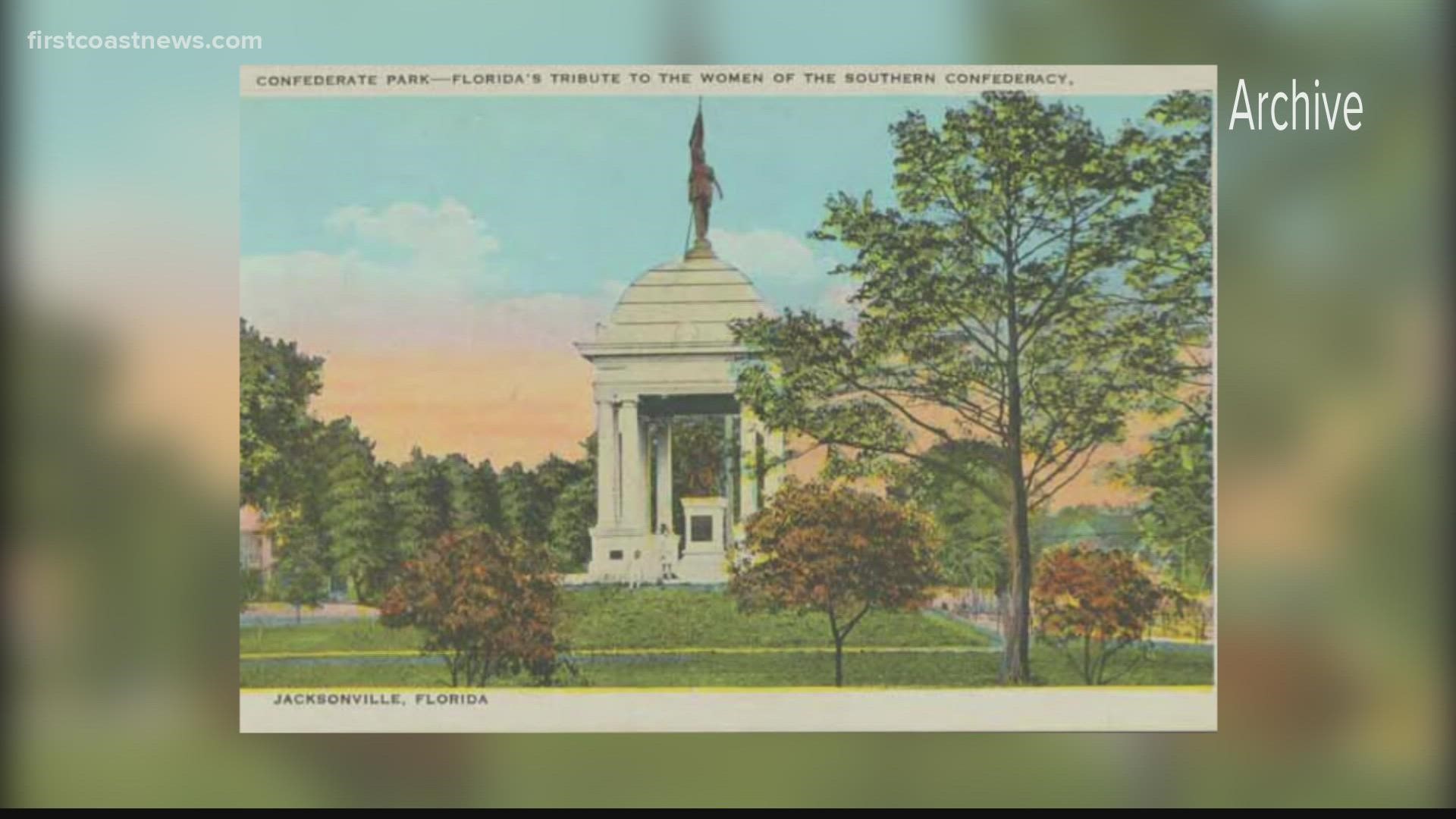

The monument is currently under a tarp in what is now Springfield Park. The name of the park used to be Confederate Park.

In 1915, 50 years after the Civil War, a crowd of thousands came to see the monument for the first time. Music played. There was a parade. There was fanfare.

"Springfield was, at the time, one of the leading residential sectors of the city," Dr. Alan Bliss, CEO of the Jacksonville Historical Society, said.

"Jacksonville was the biggest city in Florida," Bliss noted. "It was significant economically, politically, culturally."

Segregation was legal in 1915, and lynchings of Black people took place in Florida. In 1915, the monument was behind Confederate flags until it was unveiled.

With a woman and two children at the center of the memorial, it was a tribute to the women of the Southern Confederacy.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy had put up many monuments in the South, but not this one. In fact, according to Lees, the organization didn’t really support putting money into this specific monument in Jacksonville, even though it was for women.

"They would rather have them donate the money to scholarships for women," Lees said.

The United Confederate Veterans erected the memorial, but the state paid for more than half of it.

"And that was in response to appeals by the United Confederate Veterans who said, 'Hey, isn't this a great idea?' We know this about the Florida legislature of the 1910s: All white and all male. And so they were reponsive to those appeals," Bliss said.

Lees said this monument, like many Confederate monuments erected decades after the Civil War, perpetuated the Lost Cause, "a propaganda program that would talk about why the Civil War was not about slavery. And why the values that they fought for were proper and right."

However, Bliss does not necessarily agree with that notion.

"We can't see into the hearts of other people."

He said if people choose to assert that what is motivating them is a sentiment for things that pertain to their ancestors and their family, "I don't think we've got too much choice, but to take them at their word."

Even though the monument is said to honor the women of the South, it really honors the white women at the South, Lees said.

A poem read at the unveiling made it clear it was not to honor all women in the south, Bliss noted.

"She was making reference to the women who stayed home and cared for 'hearth and home and children, while the men in gray marched away,'" Bliss said, citing the poem. "And so this does not appear to be a reference to the enslaved women to the South, or free women of color or anyone else. It's a reference to the women who supported the soldiers who served in a Confederate army."

And now, it sits covered-up with its meaning and value in question.