In December 2016, Sgt. Chad Collier resigned from the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office.

The “resigned” part is important.

He’d had three ex-girlfriends accuse him of stalking or violence. He’d been arrested on suspicion of kicking in a girlfriend’s door. He even attempted suicide in front of his mother, according to police reports, shooting out his left eye with his JSO-issued handgun.

But he wasn’t fired. Because the complaints were different enough from each other, and because enough time passed between them, the 25-year veteran escaped the agency’s escalating punishment known as “progressive discipline.”

Collier’s case was complicated by the routine destruction of records, which prevents even the sheriff from knowing an officer’s full discipline history. It was also complicated by the realities of domestic violence court, where allegations are not evidence of wrongdoing.

First Coast News reviewed hundreds of JSO discipline records and attended domestic violence court appearances by multiple officers over the past two years. In most cases, officers facing either civil or criminal allegations of stalking or violence remain on the job. Only rarely do the allegations against them become public, and unless an officer is disciplined by the agency, official records are scant.

State law requires that JSO retain records related to significant discipline, like a suspension, for a minimum of 5 years. Beyond that, policy is shaped in negotiations with the powerful police union. And those negotiations have interpreted state law not as a minimum, but a maximum.

No matter how severe the allegation, even if the officer is demoted or suspended, the supporting documents are destroyed after five years. All the agency keeps is a two or three-line summary that lists the allegation and the punishment.

Lt. Chris Brown who oversees JSO’s Professional Oversight Unit says record destruction is designed to prevent a single incident from dogging an officer his entire career. But even he sometimes wishes more information was available.

“It just doesn’t answer a lot of questions,” said Brown of the discipline summary. “One of the good things about being able to go back and visit a case that we, unfortunately, may have purged, is to see all the fine lines in there, and all of the other information -- whether it be more damning or mitigating.”

“It’s unfair to the reader that that’s all they get,” Brown noted. “But, again, it is what it is.”

*****

The hallway outside of domestic violence court radiates with suppressed feeling – simmering violence, grinding jealousy, fear. They arrive early and line the benches, before entering a nearly perfectly gender-split courtroom: Petitioners on the left, respondents on the right. There, in the glare of fluorescent lights and total strangers, they grimly recount their worst days.

For Missy Whiddon, the obvious pressures of Domestic Violence court were compounded by the fact that she was seeking protection from a JSO officer.

“I absolutely felt pressure,” Missy Whiddon told First Coast News when she sought a protective order against JSO Sgt. Howsey Bowers in October 2016. “Because he’s an officer, it’s like ‘do you want to ruin his career?’”

Girlfriends and spouses of men in uniform often must weigh their desire for protection against other implications. A permanent injunction can damage a career, and an order that results in the surrender of weapons can destroy one. For couples with children or shared finances, job loss brings its own peril.

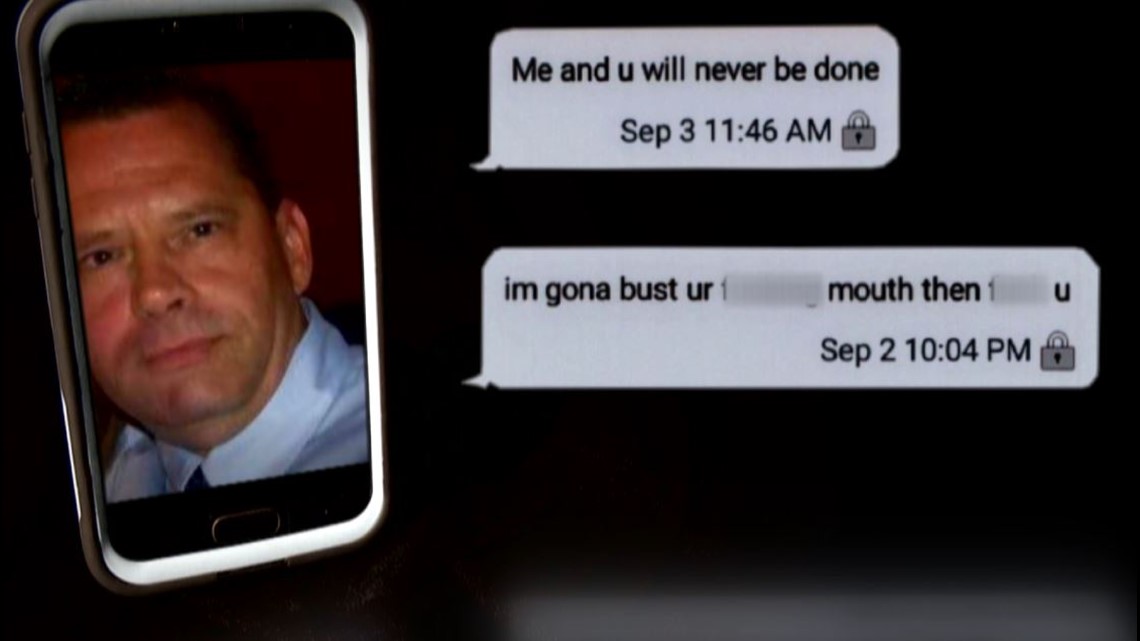

Whiddon didn’t worry about Bowers’ job security. She worried about her own. She claimed he’d choked her and threatened to kill her. In court, she produced more than 50 obscene, threatening text messages from him that promised beatings, even rape.

“When I bust your lip, u keep ur mouth shut about it,” he wrote in one. “You will not talk to other cops, if I catch u cheating on me they won't find u for a long time.”

In another one he wrote, “I’m gonna beat the f*ck out of u if u keep on… remember that when I fist f*ck you till you bleed.”

A judge dismissed Whiddon’s complaint. Sgt. Bowers insisted the pair had engaged in consensual “rough sex,” and the judge noted that Whiddon had deleted some of her own texts. Until Bowers’ voluntary resignation three months later, he remained on the job. (Bowers could not be reached for this story, but declined comment when the protective order was filed.)

When Sgt. Collier appeared in the same courtroom in April 2016, he wore the residual signs of violence – a red scar and missing eye a testament to his suicide attempt.

His ex-girlfriend testified Collier sent her 50 to 60 text messages a day and exhibited frightening behavior, including once throwing a salad across the room. In her injunction request, she said she believed she was in “imminent danger,” noting he’d already shot himself. (Collier declined requests for comment.) The judge denied her request for a protective order, saying the only violent act that Collier had committed – his suicide attempt -- was against himself.

After court, the woman said, “It's going to take myself getting hurt by him for them to go, 'Oh, maybe I should have done the right thing.'"

Four months later, Collier was arrested on suspicion of stalking.

JSO officials are notified when one of their own turns up in domestic violence court, but allegations alone don’t trigger disciplinary action. Officers are due their day in court, like anyone else. And JSO policy limits what the agency can do, particularly if allegations don’t impact an officer’s job performance.

“It doesn’t mean we aren’t aware of it,” Undersheriff Pat Ivey told First Coast News. “But there’s a lot of factors that play into this -- the Police Officer’s Bill of Rights, the administrative process for civil service, and then obviously criminal proceedings.”

*****

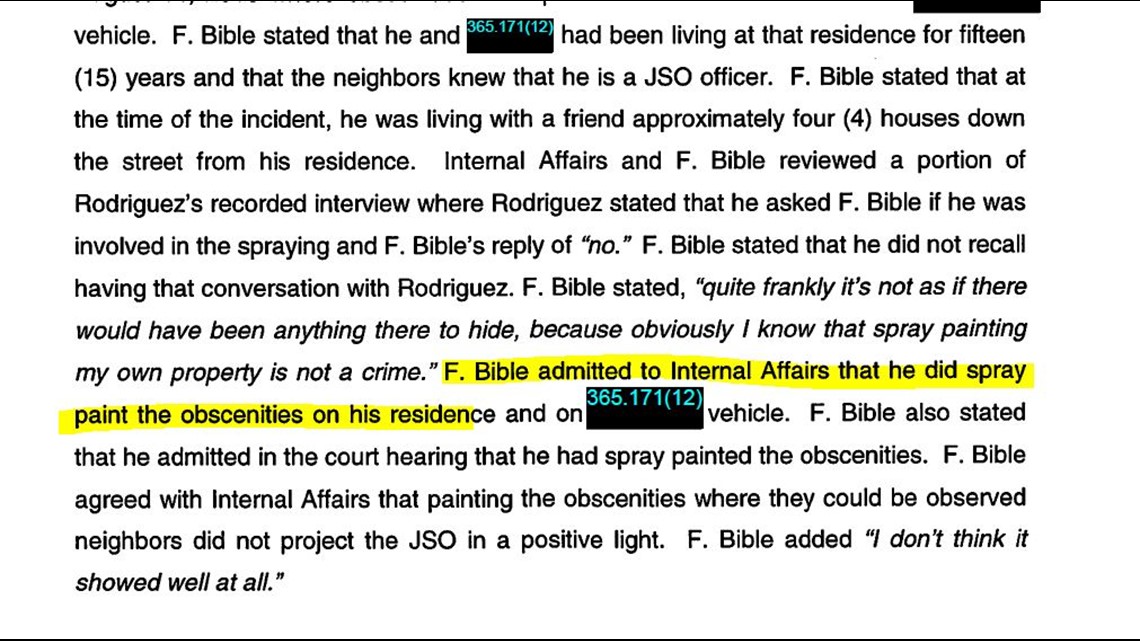

The case of Officer Fred Bible highlights the split between private life and public service. In August 2016, according to police reports and JSO internal affairs documents, Bible -- while on duty and in uniform – left his assigned zone on the Westside and drove to East Arlington. There, he confronted his wife and a man he suspected was her boyfriend.

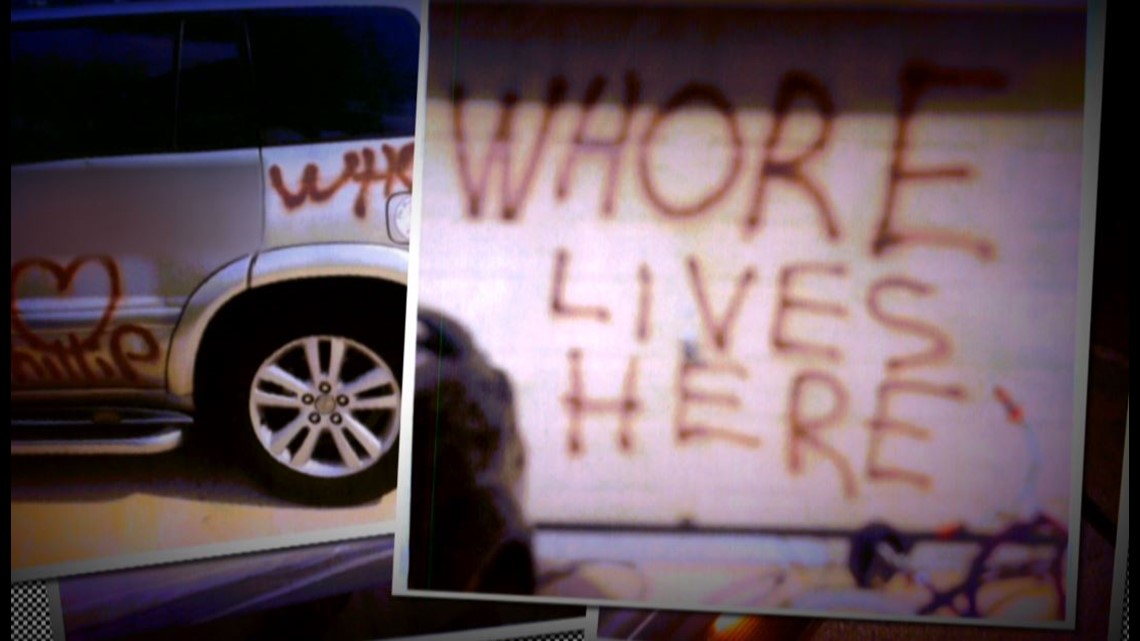

His wife told police and internal investigators he spit in her face and the other man’s face, used a racial slur, kicked in their car door and called her a slut. The following day, she told police, he came to their house and sliced up her underwear and her Sleep Number bed, peed on her shoes and spray-painted the word “whore” on her house and car.

Police records show Bible admitted the spitting, the spray painting, the kicking, the screaming – pretty much all of it except the underwear, the slur, and the shoes. He also admitted he used JSO’s database to search for the man he’d spit on, then went to his house and confronted his wife.

“I take responsibility for that,” he said in his interview with internal affairs detectives.

But his comments show a nuanced accountability. According to the officer who initially responded to the apparent vandalism, Bible denied spray painting the house. Later he told JSO investigators he had done it.

“The easy answer is, yes, I did that,” he said. “Obviously, quite frankly, it’s not as if there would have been anything there to hide, because, obviously, I know spray painting my own property is not a crime.” (First Coast News was unable to reach Bible for comment.)

The State Attorney’s Office offered Bible what’s known as “deferred prosecution” for battery (the spitting) -- a kind of amnesty in exchange for getting counseling, and avoiding his wife. JSO also suspended Bible for 15 days.

But the limit of JSO’s oversight was clear in an audio transcript of his interview with Internal Affairs Detective WC Watkins.

Watkins gently chastises Bible for spray painting the house and car. “People in the neighborhood know you’re a police officer. Writing those kinds of obscenities -- do you think that projects a good light for the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office?”

Bible concedes not. But Watkins gives him a pass for the damage inside the home, including smashed pictures and the ruined Sleep Number bed.

“Whatever happened inside the house … there’s nothing to discuss regarding that. Because that’s inside your house, and that’s your property. Whatever you did in there was between you and your wife and your children.”

According to Undersheriff Ivey, Bible continues to work in a patrol capacity, which includes responding to domestic violence calls. In a statement, he said he didn’t see that as a cause for concern.

“He is currently assigned as a patrol officer whose duties include conducting domestic violence investigations,” Ivey wrote. “I would not have returned Officer Bible to this assignment if there was any reason to believe he was unable to perform all of his required duties — including conducting fair and thorough domestic violence investigations while being sensitive to victims’ needs.”

Bible expressed regret about what happened. He told Det. Watkins, “It was probably the lowest point in my adult life and career.”

But his interview includes a startling confession that wasn’t contained in any prior report. He told the investigator that at one point during the confrontation with his wife, he was shouting for the man he thought was her boyfriend. When the man appeared behind him, Bible says, he was startled.

“I’ve been policeman a long time, so when I get startled, I immediately pulled my gun. I don’t know how I didn’t shoot somebody,” Bible said. “Only by the grace of God did I not hurt or kill someone that night.”

In 2017, Sgt. David Oliver’s ex-girlfriend accused him in court documents of stalking. Her handwritten request for protection said he said he showed up at her job, at Baptist Medical Center, and showed her cell phone videos of the two having sex. She said he threatened to show the videos to her co-workers and new boyfriend.

She said he also threatened to “get” her boyfriend, telling her he “was going to put a bullet in [his] head.”

Oliver’s first court date was canceled. As soon as Oliver stepped to the podium, the judge recognized him, and declared a conflict. Before the second court date, Oliver’s ex-girlfriend dropped her complaint – something that happens frequently in domestic violence court.

Something less common -- her complaint disappeared from the county website.

First Coast News obtained the original injunction request when it was filed by Oliver’s girlfriend in 2017. But those once public documents are no longer on the county court website.

Asked if the documents had been purged or sealed, Clerk of Court Public Information Officer Brian Corrigan responded, “If such a case existed, there would be no information regarding it available.”

A second Oliver case is still available, however. According to court records, in 2008, Oliver’s ex-wife accused him of threatening her and pointing a gun at their daughter. She said he “is constantly stating to me, ‘If you mess with my job, I will kill you and they will never find your body.’ I am in fear for my life.”

Oliver filed his own complaint, accusing his ex-wife of trying to imperil his job.

She later dropped her request for protection. Oliver remained on duty until April 6 of this year, when he retired. (First Coast News was unable to reach Oliver.)

“There’s a lot of challenges to cases which involve situations where there is emotional feelings-involvement,” Undersheriff Pat Ivey said in 2016 when asked about domestic violence complaints against officers. “Because you really have to sort through the facts.”

Ivey noted that JSO officers face enormous stress that can affect their conduct. “You gotta remember: Policemen are people too. And I’m not saying that to make light or downplay any conduct … But we have to remember we’re dealing with people who all day long, every day, do nothing but deal with other people’s problems on top of their own. That’s just reality.”

Ivey is the final arbiter of discipline at JSO. “If it does involve a suspension demotion or termination,” he says, “then that culminates in my desk.”

But even Ivey has dealt with some degree of domestic conflict.

Though not on the scale of the other cases cited in this story, the incident was reported to police.

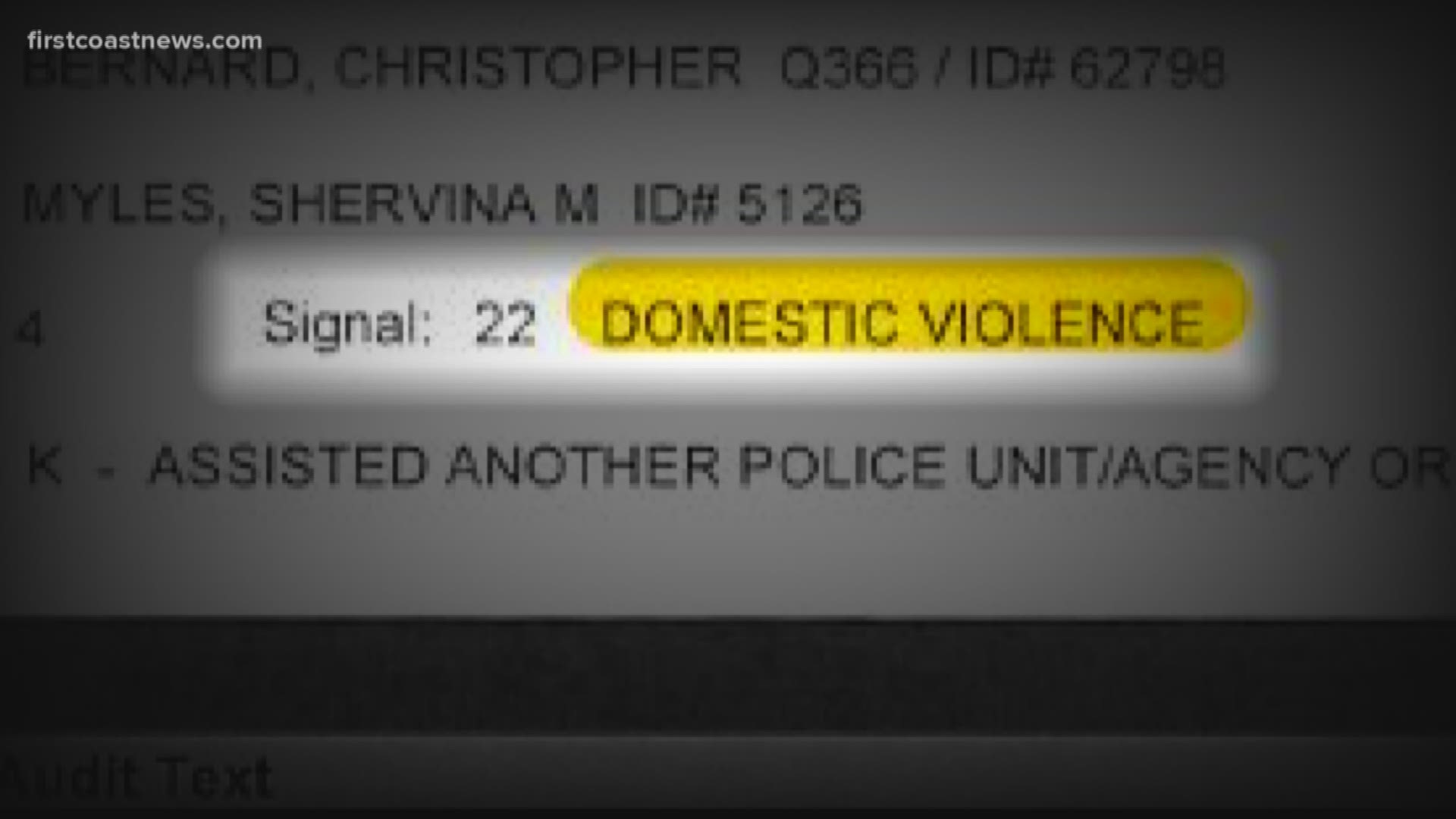

A Computer Assisted Dispatch (CAD) report from August 2014 shows his adult son called 911 at 2 in the morning to report his parents were “fighting.” The call went out as a Signal 22 – “Domestic Violence.”

The younger Ivey – a corrections officer at the Duval County Jail -- told dispatchers his father “is a chief” and had a gun. There were no specific allegations of violence in the CAD report, and no police report was ever written.

Ivey declined a request in early May to discuss the incident, and instead issued a brief statement:

“I have candidly spoken about this occurrence many times in the past, including with members of the media. At no time during this private matter did any involved party make any allegation of misconduct.” (First Coast News could find no published reports of the incident.)

Late last week, when notified this story was set to air, Ivey called and spoke at length.

Ivey initially insisted there was no mention of domestic violence in the report. “If you’re putting the word ‘violence,’ then I’m telling you that is inaccurate,” he said. “Before this mistake is made I will retain an attorney.”

When sent the document via email, Ivey conceded the words “domestic violence” appear as a description of the Signal 22. However, he correctly noted there is no mention of any actual violence in the report. And he objected to being “lumped” with other officers accused of domestic violence in this story. (First Coast News furnished JSO a list of officers that would be mentioned, as part of a request for comment.)

Ivey declined to discuss exactly what prompted his son to call 911, saying “It’s a private matter, with no violation or law violation.”

“There is truly no threat no violence. It’s merely an argument with me and my wife,” Ivey said. “Make sure this quote gets in there: I tried to stop you from making what I know is a mistake.”

Within hours of that conversation, Lt. Brown said the agency was working to correct the “system error” that resulted in the Ivey callout being labeled domestic violence.

Brown noted that the correct code for a Signal 22 is ‘Domestic’ – basically “any call involving domestic factors.” He said a domestic that involves violence should properly be called 22-88, and added, “We are in the process of changing this error in our system.”

Within 24 hours, Brown wrote, “This system error has been fixed."

Brown had previously used the undersheriff as proof that the agency does not play favorites when it comes to discipline. Ivey received a written reprimand for a January car crash, along with a 10-day loss of his take-home vehicle.

It was the sixth chargeable traffic crash in his record.

“If anybody could somehow finagle special treatment it would be him,” Brown said. “But he received a Written Reprimand Level 1, which I can imagine at many other agencies would be unheard of. … So that set the tone -- that staff is treated the exact same way that any other member would be.”