Officers found guilty of excessive force in Florida doesn't mean they lose certification

The state doesn't have a universal or streamlined standard for defining what exactly constitutes excessive force.

The death of George Floyd sparked a nationwide conversation about excessive force. What exactly is it? When can it be used?

With a guilty verdict returned against a Minneapolis police officer, some felt a sense of relief — they felt justice had been served — but had it?

A bad officer is off the streets, the streets are safer now, right? What if we told you in the state of Florida, just because an officer is found guilty of excessive force doesn’t mean they lose their certification?

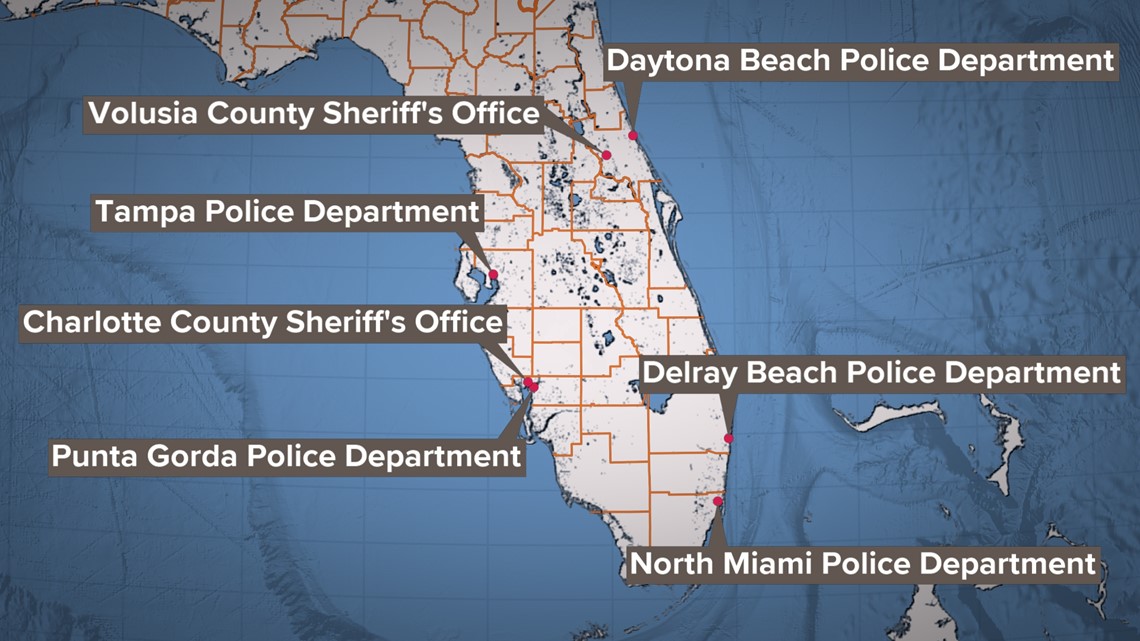

During our six-month investigation, we uncovered hundreds of instances of just that — officers being found guilty of excessive force and losing their jobs but not their certification. We also found that excessive force data is a mess in the state. Complaints aren’t tracked on a state level and, locally, data is not always readily available.

Plus, there are agencies not sending sustained cases to the state although it's necessary, per the Florida Department of Law Enforcement manual. And on top of the data being a mess, we tracked down a national law that would require the attorney general to be collecting the information.

It was passed 25 years ago and has not once been followed.

Handling excessive force cases

On Sept. 22, 2016, a teenager tried to run from police after being pulled over in Coral Gables, a suburb outside of Miami.

“The officer that clipped me with the car comes, walks past me and kicks me in my face,” said the teen during an interview with Coral Gables police. "He kicked me twice...then he said, ‘is there any cameras’. He looked around.”

Chief Edward Hudak of the Coral Gables Police Department said his agency took action: “Our officers did not stand for the violence; they notified their chain of command right away. And that officer never stepped foot in a Coral Gables police uniform again.”

An internal affairs investigation was launched.

“Which is their due process that went on for a year. Once that was done, I made a recommendation to my city manager for termination,” Hudak said.

But in the state of Florida, excessive force cases found to be sustained don’t stop there. While complaints are not tracked by FDLE, sustained cases are turned over to the Criminal Justice Standards and Training Commission, or the CJSTC.

The CJSTC is made up of 19 members that include law enforcement, from sheriffs to police chiefs to correctional officers. There is also a citizen on the committee that is appointed by the governor. The commission oversees an officer’s discipline if an internal affairs investigation sustains a moral character violation, which includes excessive use of force.

Commission members decide whether an officer loses their certification, which allows them to work as law enforcement in the state of Florida.

As mentioned in the case in Coral Gables, while the officer was terminated from his current department, he didn’t lose his police certification. Instead, that certificate was put on suspension.

“We received notice later on about what the stipulation was, so that's what came back to us,” Hudak said.

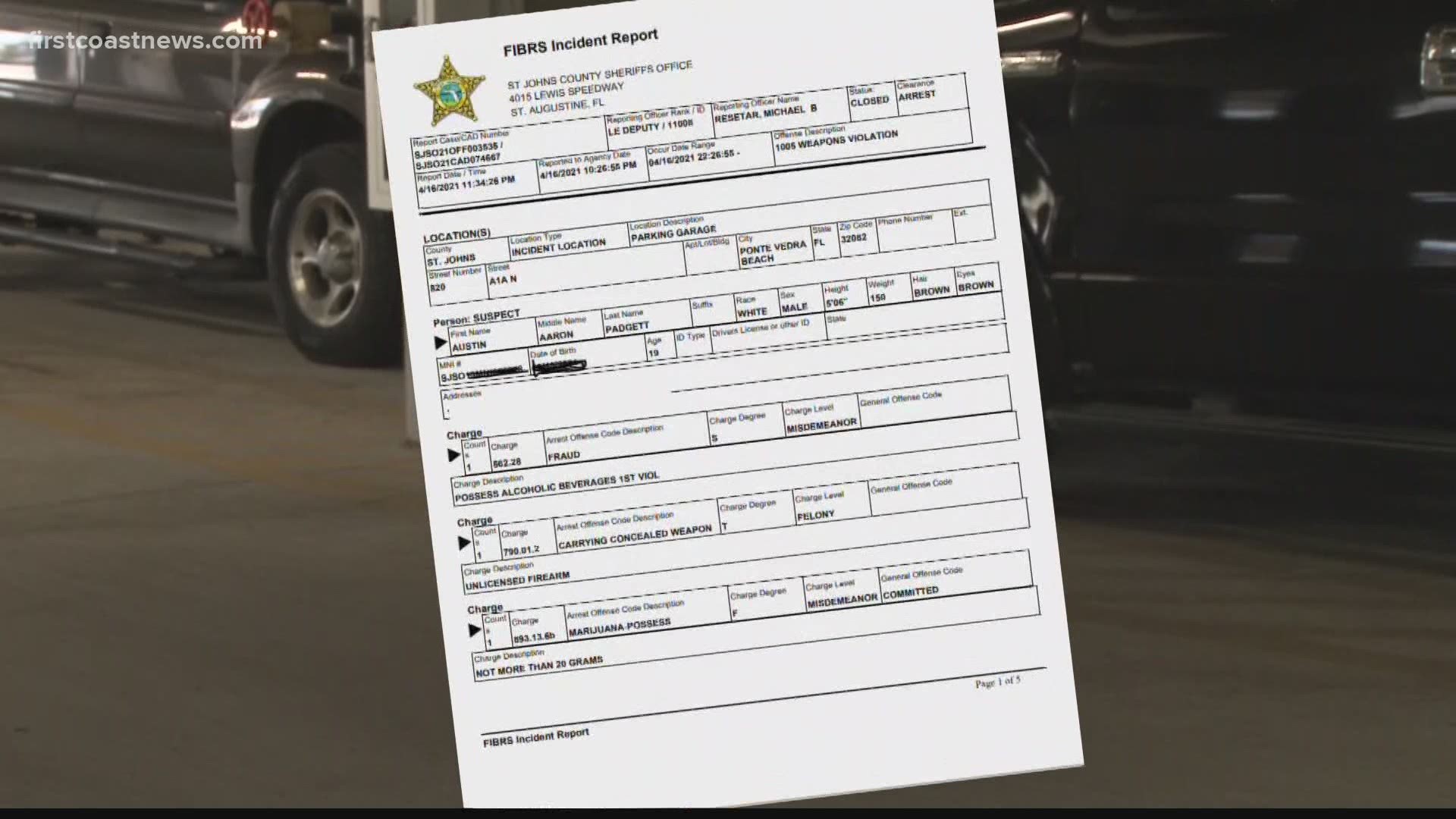

10 Investigates requested data from the FDLE showing every time an excessive force case of an officer was sustained, and we dug in for six months — even enlisting the help of a data journalist at 9Wants to Know in Denver. After weeks of combing through that data, we discovered 1,776 cases of excessive force ruled as sustained since 1985.

Of those, only 436 reached a conclusion. Only 158 had their certificate revoked.

The others were either given a suspension or put on probation, like a former Zephyrhills officer accused of using excessive force by deploying his Taser when it was not needed.

There was a case in Manatee County where a deputy struck an inmate with his knee multiple times while the inmate was being held down on the floor.

“It could be a situation where they're in the heat of the moment, they're in a fight for their life, they get carried away, they commit excessive force, they do face consequences, that job loss, potential prosecution, potentially losing their certification," Bay County Sheriff Tommy Ford said. "And then there's other situations if it's done with malice and unprovoked, say they strike a handcuffed inmate or something like that.

"They, you know, that's a whole different situation where we're looking at criminal charges and revocation of the certification.”

Ford is the current chair of the CJSTC.

“I can't speak to the prior commissions and what happened then, but I know that the group we have taken takes it very seriously, and certainly realizes the public sentiment on those issues, and really worked hard to make the right decision,” Ford said.

Charlotte County Sheriff William Prummell says things are different now than in the past.

“I have somewhat seen a change where, you know, in this environment right now, the commission is more apt than holding people accountable. And there's been several instances, over the course of the years that I've been there where commissioners have rejected staff’s recommendation of a suspension or a training or anything that and have gone for revocation,” Prummell said.

Hudak said he was not going to accept the 2016 incident involving his officer and the teen as just.

“It was just was not. And there was no body camera footage on that. That that panel voted to do whatever they wanted to do. But I'm comfortable in the fact that what FDLE has put into effect is that anybody that is a CEO like me that wants to hire that individual, if they don't do their due diligence, that's on them,” Hudak added.

Hudak says that’s because a background check would bring up the officer’s history.

But 10 Investigates found some officers disciplined for excessive force continued to work at their current agency. Like a case in Fort Myers, where the officer was suspended but is still working for the department.

Others moved agencies and continued to work.

Warren Bunts says what happened to him last October wasn’t right

“I had my handcuffs on what was that doing? I mean, it wasn't doing any there was no violent behavior,” Bunts said.

His wife filed a complaint with the Citrus County Sheriff’s Office, claiming the officer on scene used excessive force on her husband.

“And he hit me in the head with whatever part of his body,” Bunts said.

That officer was terminated after an internal affairs investigation. Even so, Bunts wonders what will happen next to that officer.

“I really believe that there should be more discipline, absolutely. Action taken against," Bunts said. "Yes, there's that commit except just more — yeah, they need more training. It sounds like.”

This past year, the state of Florida passed HB7051-Law Enforcement and Correctional Officer Practices.

It states that beginning July 1, 2022, each law enforcement agency must report data quarterly to the FDLE regarding the use of force by the law enforcement officers employed by the agency that results in serious bodily injury, death or discharge of a firearm at a person. This data must include all information collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Use-of-Force Data Collectio, on use of force incidents that result in serious bodily injury, death or discharge of a firearm at a person.

But that doesn’t include complaints and only cases that cause serious bodily injury, which is once again some experts say, up to agencies to decide.

'He was just a great dad'

Charlotte County Sheriff William Prummell is one of the 19 members on the Criminal Justice Standards and Training Commission.

The board decides the fate of an officer if they are found guilty of a moral code violation, including excessive force. FDLE does not track excessive force complaints. It does, however, track the sustained cases sent to the commission.

So then when it comes to excessive force cases, if a case was found sustained, that should be sent to the commission, right?

“Yes,” Prummell said. But 10 Investigates discovered that is not always the case.

Take for example the Sarasota County Sheriff’s office. While there were four sustained excessive force cases within the department over the past 10 years, we know half of them didn’t make it to the state.

One man settled with the city for $90,000 of taxpayer money after an excessive force complaint was filed following an incident with him and a deputy. That incident resulted in a plate having to be surgically implanted into his face.

That officer was put on leave and reeducated.

In 2018, an administrative investigation was launched after a deputy was seen punching an inmate three times in the face. According to the report on that excessive force case, the force used was “unnecessary” given the level of resistance from the inmate.

But those cases never showed up in any of our documents from the state. We asked why.

In an email, the Sarasota County Sheriff’s Office told us the case was never sent to the state “because the force violated our internal policy,” not the state. But according to the FDLE manual, a moral character code violation is a non-criminal act of conduct, which includes excessive force.

When we showed the sheriff’s office what we found, they sent us an email explaining:

The language you are referring to in the handbook is a summary of the governing rule – 11B-27.0011 Moral Character. Section (c)1. of the rule, which addresses reports of excessive force to FDLE, defines excessive force cases to be disclosed to FDLE as:

“Excessive use of force, defined as a use of force on a person by any officer that is not justified under Section 776.05 or 776.07, F.S., or a use of force on an inmate or prisoner by any correctional officer that would not be authorized under Section 944.35(1)(a), F.S.”

Chapter 776 is found in the criminal statutes and Chapter 944 specifically governs the Department of Corrections (Florida State prisons, not county jails).

This was the analysis and determination made at some point in the past – most likely during the 17-year tenure of our former Internal Affairs lieutenant, or even before that. Since your inquiry, we reached out to FDLE for clarification. Per general counsel at FDLE, we should (not shall) report our excessive force policy violations to them. When received, they typically stipulate to the discipline administered by the agency with no further action taken. While our past practice was not a violation of Rule 11B-27.0011, we have chosen to update our practice to submit all sustained excessive force cases to FDLE going forward.

And then take the case of Daniel Daly.

“I idolized him. Yeah, I mean, he was just a great dad, you know, I mean, he really was,” said Greg Daly, son of Daniel Daly. Greg Daly says a day doesn’t go by when he doesn’t think about his father who passed away last year.

“He just he helped people too much,” Daly said.

So, when he got a call letting him know his 84-year-old father was in the hospital after an encounter with an Orlando police officer, he couldn’t believe it.

“He broke the C [two], which is called a hangman's break, at what snaps when you get home says people don't live when this is broken to the extent this is,” Greg Daly said.

Bar owner Tim Scott witnessed the entire encounter.

“He just for whatever reason to have to pick them up and slam them into the ground like he did. And I, and literally, it was hard to watch because his literally his feet were in the air,” Scott said.

“And it just piled drive them right into the ground. It was way too much excessive force.”

Daly was later rewarded $900,000 from the city of Orlando for his excessive force complaint, but there was never an internal investigation conducted regarding excessive force, so it’s not part of the state statistics.

“I'm not sure what constitutes excessive force then. I mean, other than that, I mean, to be brutally slammed to the ground. An old guy like wasn't some muscle guy. I mean, yeah, it was old man,” Scott said.

This was all uncovered as we tried to track excessive force complaints at Tampa Bay-area departments ourselves.

How many of those were sustained and sent to the state?

We found some departments didn’t have that info readily available, so it would cost us hundreds of dollars for that answer. Other departments had the info but like the Sarasota County case, not all agencies were reporting sustained cases to the state.

And like the Orlando case of Daniel Daly, his case wasn’t investigated by internal affairs. Officials with Orlando Police said if that happened today, it would have been investigated, which shows the discrepancy in numbers from even 10 years ago.

So that’s why some say we’ll never know exactly how many excessive force cases have happened in the past

“Nope. And you never will. Even though there's let's say, even if we have a universal standard, which we don't, you must understand that there is an operational side to the way a police department operates,” said David Thomas, a professor of forensic studies at Florida Gulf Coast University. He is also a former law enforcement officer of 25 years.

Thomas says universal standards mean a state statute that defines exactly what excessive force is.

“What one agency may view as excessive force, what one supervisor may view as excessive force, another one may not. And so that's you know, that's going to be I think, the difficult part until we until they decide we're going to train everybody the same all the supervisors, this is going to be the universal thing. And then this is how we expect you to look at it and this is how we expect you to report it,” Thomas said.

The data just isn't easy to find right now, Prummell said.

“That's the honest truth. It's not easy to find right now. You just got to hope that your law enforcement leaders are doing the right thing,” Prummell continued.

“I would say we probably don't have a really good standard database that covers all different levels of excessive force. I mean, now we're reporting more or less than anything that results in great bodily injury or death. That's getting reported, but again, it's not being reported by every agency.”

The FBI has started to collect use of force data but that only represents agencies who voluntarily report these cases that result in great bodily injury or death to the FBI database.

But that does not include all complaints.

Data collection is 'critical'

The federal government should be tracking these cases, too. It's part of federal law that was passed in 1994 — a law that then-Senator Joe Biden had a big hand in writing. Title 42, section 14142, requires the United States Attorney General to acquire data on the use of excessive force and to report on it annually.

We emailed the attorney general's office for all 25 annual reports.

They admitted the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act requires the attorney general to acquire data about the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers, but they didn’t attach any of those reports we requested.

Instead, they sent us a link to the Bureau of Justice Statistics where they say they’ve made efforts to acquire that data.

“Has that ever happened? Have we ever had an annual report?”

“Not, not to the spirit of the language of that statute? I mean, the intent there was that every year there would be a report on use of excessive force by police,” said Matt Hickman, a professor at Seattle University. He used to work at the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

He says they attempted to collect data from police departments on citizen complaints about police use of force in 2002, even published it. The author of the report? Hickman.

“That was the first and last time that it was collected and reported, after I left BJS subsequently collected additional waves of complaints data, but they never published them,” Hickman said.

“To be fair, it's not easy, right? Collecting data on the use of force, just the use of force is a massive undertaking, much less the use of excessive force. it's challenging. And that's, does that mean, we shouldn't do it? No. Does that mean that we shouldn't try? No. But it's never been properly resourced.”

10 Investigates reached out to Florida’s two members of the House of Representatives who are on the Congressional Law Enforcement Caucus, Democrats Val Demings and Debbie Wasserman-Schulz, for months to ask their thoughts about this and if they would push for the law to be followed.

Neither had time to speak to us.

“Congress needs to pass a law saying this is mandatory that agencies will report data on the use of force to the federal government. So you need you need Congress to pass a law. Second, you need to resource it properly,” Hickman said.

Some experts say the data collection is critical because it would give agencies a better look at where possible trends lie and possible training that could be implemented.

This data would also provide transparency to the community, helping to build relationships between law enforcement and the communities they serve.

“I think there should be a database, if not statewide, nationwide,” said Jason Dragash. Dragash says he was the victim of excessive use of force by a Sarasota Police Department officer. That officer was found guilty after an internal affairs investigation.

And that’s the big thing we’ve uncovered during this investigation and talking to experts: While not every officer who is found to have used excessive force should be blacklisted from law enforcement, experts say this points to the need for better training.

New way to train

It’s a Scottish tactic to deescalate high-stress situations, and several law enforcement agencies in the state of Florida have implemented the training as a way to have officers use force less often.

It’s called ICAT — a training program that provides first responding police officers with the tools, skills and options they need to successfully and safely defuse a range of critical incidents.

According to the program’s website, seven agencies in Florida are now training their officers with ICAT. The Tampa Police Department was the first one in the Tampa Bay area to do so.

“We never like to respond to resistance or use force. Again, if this is something that allows officers to look at other options, if there’s one situation that gets resolved better as a result doesn’t that work out better for everybody,” said Jared Douds with the Tampa Police Department.

In the spring of 2020, protests broke out across the country following the murder of George Floyd. Those protesting called for changes within law enforcement agencies. Many departments, including those in the Tampa Bay area, did implement new policies and training.

Tampa introduced ICAT to its officers at the beginning of this year.

“The concepts behind ICAT aren’t really something that’s new to TPD. It’s something we’ve been using under different terminology or approaching it from a slightly different angle for years. It wasn’t a dramatic shift for us which is positive in a lot of way. So this just packaged in a way so if it made officers buy into it or understand it a little better, it works out for everybody,” Douds said.

Douds also went on to say that in this day and age, this type of training is very important.

“Especially if they haven’t already been doing something like this,” Douds said. “Or if it’s a reinforcement of what they’ve been doing again if it can help officers out there make better decisions and better resolutions. Again, making community better itself.”

Douds says there have already been encounters with people where officers have used what they learned from the training.

We are told other agencies in the region are also beginning to train their officers with ICAT.