WASHINGTON, D.C., USA — Inauguration Day has been a tradition in the works since the beginning of the presidency. Over the years, several traditions arose including the president choosing the Bible on which they would swear the Oath of Office and the number of inauguration balls he and his wife attend. However, the inaugural address has been at the center of the day’s festivities since the beginning.

The speech allows the new president to set his agenda going forward, as well as inspire the country in times of trial and change. These speeches have gone into history as defining not only the presidency itself, but sometimes even the spirit of that president’s generation.

Here are some of the most notable inaugural addresses in history.

'But with veneration and love': George Washington (1789)

On April 30, 1789, more than five years after he led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War, 57-year-old George Washington stood at Federal Hall in New York City to be inaugurated as the first President of the United States. As the federal court system had not been fully set up, the highest judicial officer in the State of New York swore the new president into office. Then, President Washington and the Congress retired to the Senate chambers for Washington to give his inaugural address.

The Office of the President of the United States had a number of guidelines set within the Constitution, yet Congress and Washington all knew it would be up to him to define exactly what this office would be. There was no one more qualified for the job. Washington, after all, had turned the ragtag Continental Army into a fighting force that would defeat the British Empire and had presided over the Constitutional Convention that would replace the failing Articles of Confederation. Despite this, according to the National Archives, Sen. William Maclay noted Washington’s deliverance of the speech seemed to be the president’s larger than life image and persona.

“This great man was agitated and embarrassed," Maclay added, "more than ever he was by the leveled Cannon or pointed Musket."

In his speech, Washington did not attempt to hide this reluctance.

“On the one hand, I was summoned by my Country, whose voice I can never hear but with veneration and love, from a retreat which I had chosen with the fondest predilection, and, in my flattering hopes, with an immutable decision, as the asylum of my declining years--a retreat which was rendered every day more necessary as well as more dear to me by the addition of habit to inclination, and of frequent interruptions in my health to the gradual waste committed on it by time.”

Still, despite his apprehension, Washington seized the moment to make an important distinction in the president’s role in establishing law. As William Etter, Ph.D. noted, Washington used his platform to define the president as working with the legislative branch to pass laws, including charging Congress to come up with specific laws. Further, he challenged them to do so out of the interest of the country and the People, rather than out of personal or partisan interests.

“In these honorable qualifications, I behold the surest pledges that as on one side no local prejudices or attachments, no separate views nor party animosities, will misdirect the comprehensive and equal eye which ought to watch over this great assemblage of communities and interests, so, on another, that the foundation of our national policy will be laid in the pure and immutable principles of private morality, and the preeminence of free government be exemplified by all the attributes which can win the affections of its citizens and command the respect of the world.”

Washington closed by refusing compensation for his office and publicly asked for divine help for “deliberating in perfect tranquility, and dispositions for deciding with unparalleled unanimity on a form of government for the security of their union and the advancement of their happiness.”

The first inaugural address is not considered among the best in the country’s history, but like everything in George Washington’s tenure as the Chief Executive, it was the first and helped to define the role of president for the next 44 men that would hold the office.

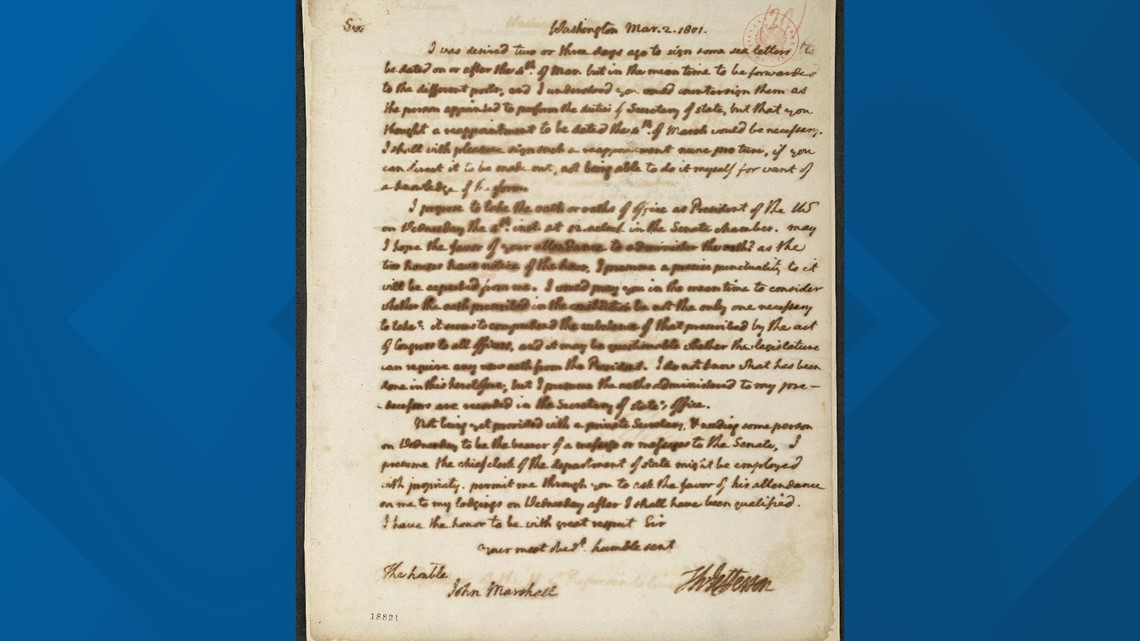

'We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists': Thomas Jefferson (1801)

Thomas Jefferson had served in the Continental Congress, drafted the Declaration of Independence, served in Congress and was Vice President of the United States heading into the 1800 Presidential Election. Yet, he took office as America's third president in controversy.

John Adams, who had become an unpopular president as his first term was winding down, had been defeated in America's first mudsling campaign. In fact, Adams and Jefferson, once friends, had now become political enemies. Despite Washington's warning of political factions in his farewell address, the feud between the outgoing and incoming president was merely a representation of the large feud between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans.

Though Adams chose not to attend his rival's inauguration, he nonetheless set the tone for the peaceful transfer of power by a defeated president. Jefferson, meanwhile, set out to unite the country.

"Let us then, fellow citizens, unite with one heart and one mind, let us restore to social intercourse that harmony and affection without which liberty, and even life itself, are but dreary things."

According to Princeton University, Jefferson purposely avoided policy and talked about political theory instead. During his speech, Jefferson acknowledged his belief in the limits of the federal government, which was at the center of the debate between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans.

"Still one thing more, fellow-citizens -- a wise and frugal Government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned."

However, the speech is still best remembered for the sentence, "We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists." It set a precedent of using Inauguration Day to unite the country during times of division.

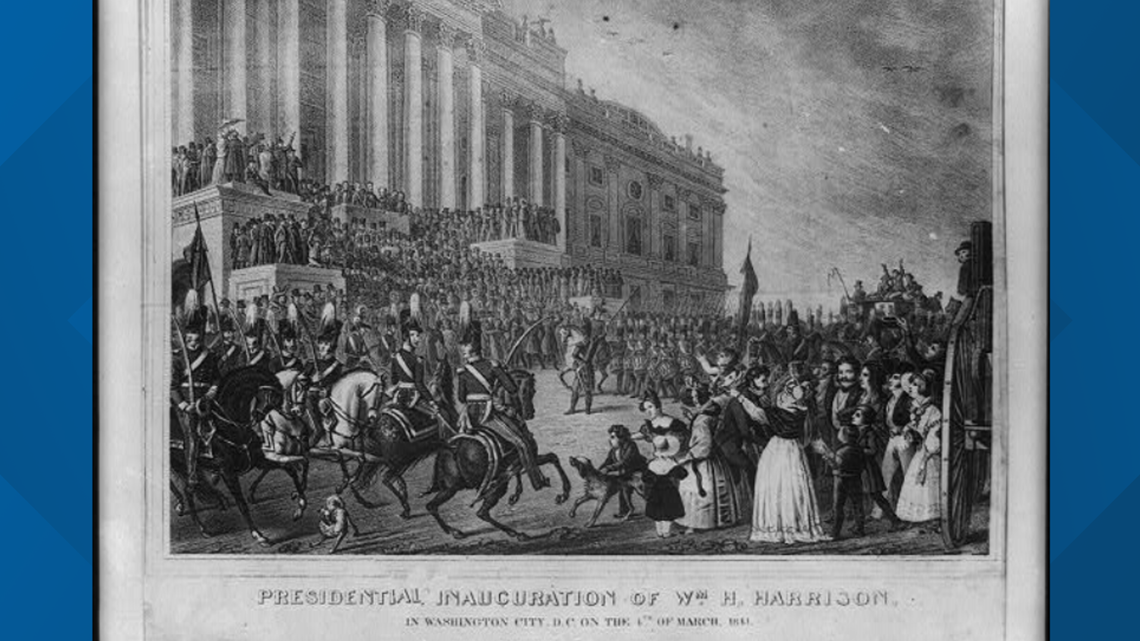

"Feelings of distrust and jealousy": William Henry Harrison (1841)

On March 4, 1841 war hero William Henry Harrison, then 68 years old, took the Oath of Office as the country's ninth president. He would be the oldest president until Ronald Regan more than a century later. His term was short, lasting only 31 days before his death on April 4.

In fact, virtually the only thing notable about his presidency is his inauguration. Yet, it was one of the most notable in history.

According to the Library of Congress, Harrison was the first president to arrive in Washington by train and his was the first Inauguration Day planned by a committee, which included a parade and ball.

Yet the speech itself was 8,000 words, longer than any in American history. Despite the cold temperatures, Harrison refused to wear any sort of overcoat to protect him from the cold.

The University of Virginia's Miller Center notes the speech was prophetic, warning the country of the deepening political division in America. The speech even mentioning the term "civil war," which would erupt only two decades later. In that reference, he warned that if one group of people attempted to wrestle control of the government from the rest, the natural order would bring about civil war and the destruction of the Union.

"The attempt of those of one State to control the domestic institutions of another can only result in feelings of distrust and jealousy, the certain harbingers of disunion, violence, and civil war, and the ultimate destruction of our free institutions."

Popular tradition holds the president's death a month later could be attributed to the speech, specifically the length of the speech combined with the colder temperature. Yet, the Library of Congress notes Harrison likely died from the water that supplied the White House, which had been contaminated by sewage.

"Better angels of our nature": Abraham Lincoln (1861)

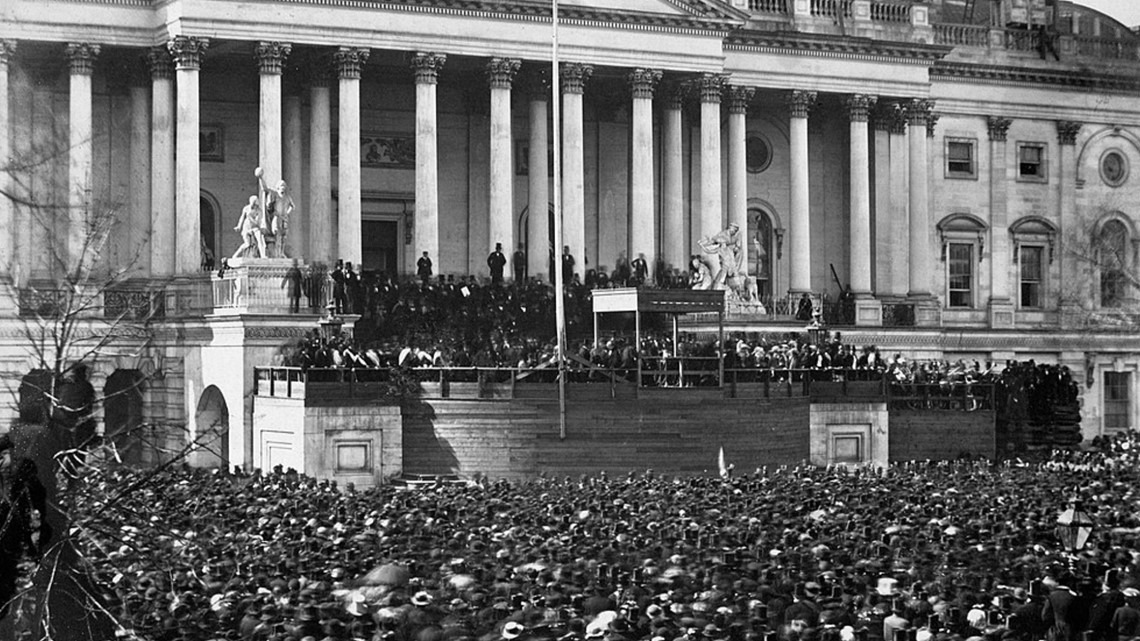

The inauguration of Abraham Lincoln was perhaps the tensest of all inaugurations in the country's history. Several states had seceded from the Union, and Jefferson Davis had already been sworn in as the President of the Confederate States of America in Montgomery, Ala. In Washington, there were plots to assassinate to the newly-elected president.

Lincoln had publicly embarrassed himself by arriving to Washington wrapped in a shawl. Then, he was publicly silent on the ongoing situation in Charleston Harbor, where Confederate guns had forced Union troops to take shelter inside Fort Sumpter. Lincoln understood the importance of the upcoming inaugural address.

As President Lincoln ascended the steps to give his speech, thousands of spectators gathered below, eyed by sharpshooters stationed on the unfinished Capitol building, while cannon guarded the Capitol ground, as recounted by Ken Burns' Civil War. Lincoln's speech was aimed directly at reconciliation with the South. He denied the legality of secession but promised not to fire the opening shot of the coming Civil War.

He began by acknowledging the schism in the country and reaffirmed his campaign promise to not interfere with slavery where it existed, saying, "I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so." Yet, Lincoln still acknowledged the issue of slavery had become a Constitutional crisis.

"Shall fugitives from labor be surrendered by national or by State authority? The Constitution does not expressly say. May Congress prohibit slavery in the Territories? The Constitution does not expressly say. Must Congress protect slavery in the Territories? The Constitution does not expressly say."

Lincoln also directed his attention toward another issue that would define his presidency, the preservation of the Union during a time of civil unrest. He laid out his belief that the federal government had the right to not only preserve the states admitted to the Union but also it held the right to protect any federal property located in any state, a clear reference to the soldiers held up in Fort Sumpter.

Lincoln closed the speech speaking directly not to his constituents in the United States, but to the people of the rebellious states, urging them to use calm and patience to resolve their differences.

"In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect, and defend it.

"I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."

'Modern life is both complex and intense': Theodore Roosevelt (1905)

Less than 50 years after the Civil War, the entire social construct of the country had changed. The Industrial Revolution had moved the country's focus from the rural farm to the city. And with the dawning of a new century, the country itself had become an economic power on the world stage. Theodore Roosevelt seemed to perfectly fit the mood of the era.

Roosevelt was already president when as he stood up to give this speech, taking over for the assassinated William McKinley. Yet, this was his opportunity to define the course the country would take in the new century. So unlike Lincoln's plea for reconciliation or Harrison's warning, Roosevelt's message was one of positivity.

"We in our turn have an assured confidence that we shall be able to leave this heritage unwasted and enlarged to our children and our children's children."

Roosevelt acknowledged the country's prosperity by challenging Americans to learn the lessons from history to achieve greater things, according to Real Clear Politics.

"Much has been given us, and much will rightfully be expected from us. We have duties to others and duties to ourselves; and we can shirk neither. We have become a great nation, forced by the fact of its greatness into relations with the other nations of the earth, and we must behave as beseems a people with such responsibilities."

The Theodore Roosevelt Association recalls the crowd at the address marked the diverse story of America up to that point with cowboys and Native Americans invited, industrialists with their workers and students who were preparing to take on the challenge issued by the new president.

"To do so we must show, not merely in great crises, but in the everyday affairs of life, the qualities of practical intelligence, of courage, of hardihood, and endurance, and above all the power of devotion to a lofty ideal, which made great the men who founded this Republic in the days of Washington, which made great the men who preserved this Republic in the days of Abraham Lincoln."

"The only thing to fear is fear itself": Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933)

In 1933, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression. Incoming President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had campaigned promising recovery through his New Deal.

At that time, unemployment had skyrocketed to more than 20%, banks across the country were closing and the industrial production that had turned America into an economic powerhouse fell by nearly 50%, according to Britannica.

However, the depression went beyond economics. According to Four Freedoms Park Conservancy, the country was also in a depression of the spirit. Roosevelt saw the responsibility of the president as not only being responsible for leading the recovery effort but also leading effort to inspire those reeling from depression.

On March 4, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated as the 32nd President of the United States. It was the last time Inauguration Day was held in March, as the 20th Amendment moved Inauguration Day to Jan. 20 thereafter. During his speech, Roosevelt urged Americans to stay optimistic about the future, despite the bleak reality of the country at that time.

"This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance."

Roosevelt continued by reminding Americans the country had faced perils before and had faced down those perils. Then, he told Americans that the depression was not their fault, rather Roosevelt blamed the depression on the unregulated actions of the "money changers."

"The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit. "

Yet, the country did not need someone to blame, but action. Roosevelt said in his speech the federal government would involve itself in programs to help people return to work and prosperity.

"Our greatest primary task is to put people to work. This is no unsolvable problem if we face it wisely and courageously. It can be accomplished in part by direct recruiting by the Government itself, treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war, but at the same time, through this employment, accomplishing greatly needed projects to stimulate and reorganize the use of our natural resources."

Roosevelt also advocated for the end of market speculation and an end to the gold standard, which he attributed as causes of the depression. He ended his speech by reassuring the American people he intended to take action to repair the country's confidence.

"Ask what you can do for your country": John F. Kennedy (1961)

By the end of the 1950's, the Great Depression was a distance memory. America seemed to be poised to continue a period of rapid growth and prosperity, thanks in part to the burgeoning suburban culture created by the families who moved to suburbs following World War II. Yet, this only masked the strife of the Civil Rights Movement and the tense standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union.

To many Americans, John Fitzgerald Kennedy seemed to embody America's idealism. However, he only edged out the popular vote in the 1960 election against Richard Nixon. For his inaugural address, Kennedy intended to inspire the nation to take advantage of their own idealistic views and apply that to improving life in America, according to the JFK Library. However, just as importantly, he wanted to show Americans he was capable of handling the issues before him.

"Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans--born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage--and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world."

Kennedy, a veteran of World War II, called focused his speech on the growing concerns of the Cold War, which seemed to be heating up. He first called for unity among the America's allies, particularly in the United Nations. He also pledged to help struggling nations with their poor, though he claimed it was purely humanitarian reasons and not for the war of words fought between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

Then, he spoke directly to the Soviet Union, though referring to them as "adversaries," calling for peace and warning the Soviets war between the world's two superpowers could mean the end of civilization.

"Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction. We dare not tempt them with weakness.

"For only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed."

Kennedy invited the Soviets to further negotiations to prevent war and bring the nuclear arms race between the two nations under control.

Finally, Kennedy issued his now-famous call to action for Americans. He reminded them of the sacrifices of the country's previous generations. Then he told them that this "new generation," invoked earlier in his speech, prepare to answer that same call should it be necessary. He closed his speech with words of justifying the sacrifice of all generations of Americans.

"And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.

"My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man."