JACKSONVILLE, Fla — The children of some of the more than 100 Holocaust survivors still living in Northeast Florida are now telling the stories of their parents — European Jews who somehow survived the Nazi concentration and labor camps, set about building families of their own, came to America and dealt with memories of an unspeakable horror that lingered throughout their lives.

It’s painful and exhausting for them to talk about it, but they want you to know of their parents as the people they were: tough, scarred, generous. Survivors.

Learn of Gloria Einstein’s father, Frank Colb, who in his early days at a Nazi labor camp was given a rare afternoon off. He was hosted by a Jewish family where he was enchanted by a young woman in a red dress — though the homeowner’s daughter kept chatting with him, preventing him from getting near her.

But he kept alive the memory of that woman in the red dress, and when the days ahead got much, much darker, he would think of her, of such loveliness in an ugly world. After the war, he met her by chance in Prague. She didn’t remember him, but oh he remembered her. They were married months later.

Look at the eyes of Louis Post’s mother, Anna, in pictures the Nazis took of her at Auschwitz, where she was prisoner 32127, the number they tattooed on her arm. She was 19 years old, her head shorn, wearing a striped prison outfit, and she had already seen so much evil.

“You can see, the eyes are dead,” Post said. “And 32127, that is still on her forearm at the age of 98.”

Look at the example of Lisa Landwirth Ullmann’s father, Henri Landwirth, who was arrested in Belgium at age 13 and spent the next five years in Nazi death and labor camps, including Auschwitz. Late in the war he was taken into the woods to be shot. But his two German guards, with the fighting so close to an end, let him live.

Run, they said. And he did.

He came to America as a young man with nothing, built a career in the hotel industry, became rich and spent decades as a renowned philanthropist helping the most needy.

“Somehow he felt like God spared his life,” Ullmann said, “and he really needed to give back to the world, helping those in need — and also, in the process, healing himself.”

Their stories are some of those told in "Holocaust Memories: Sharing Family Stories," a program established by Jewish Family and Community Services, a social-services group in Jacksonville.

Facilitated by Hope McMath, nine children of Holocaust survivors have been having workshops once a week on how to best tell their families’ stories. Those started in the spring, leading to the first presentations to schools, community groups, doctors at Mayo Clinic in November.

Those who wish to host a presentation should reach out to Jewish Family and Family Services.

All the work has been done in the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic, so everything so far has been done virtually. Even so, the sessions can be emotionally draining, even shattering, said McMath, owner and founder of the Yellow House art gallery.

Telling these stories isn’t easy.

“None of us have shared physical space together, yet we’ve had these deeply intimate exchanges,” she said. “Every week to really be present and listen and absorb and understand all these various aspects of what happened at the time, and the effect today, it’s so heavy.”

On Wednesday, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the speakers will take part in free, online public programming at jfcsjax.org featuring their stories. There also will be a virtual tour of the Frisch Family Holocaust Memorial Gallery at Jewish Family and Community Services.

Einstein, Post and Ullmann said their family stories are even more pertinent now: They were shaken by the assault of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 and sickened by the anti-Semitic slogans displayed by some of the insurrectionists.

"It was that one T-shirt that got to me: Camp Auschwitz," Ullmann said. "My family lived and were imprisoned there. To see him wearing that shirt was infuriating. It did something to me. It wounded me.”

Post said societies need to guard against the natural instinct to hate those who seem different from them. "When a government begins to dehumanize people, when a government begins to call a group evil or traitors, or starts to treat a group of people as if they’re less than human — that they really don’t want them around, they’re awful, they’re terrible — that‘s the first step. That’s where the road begins to awful, brutal things happening.”

'Could happen again'

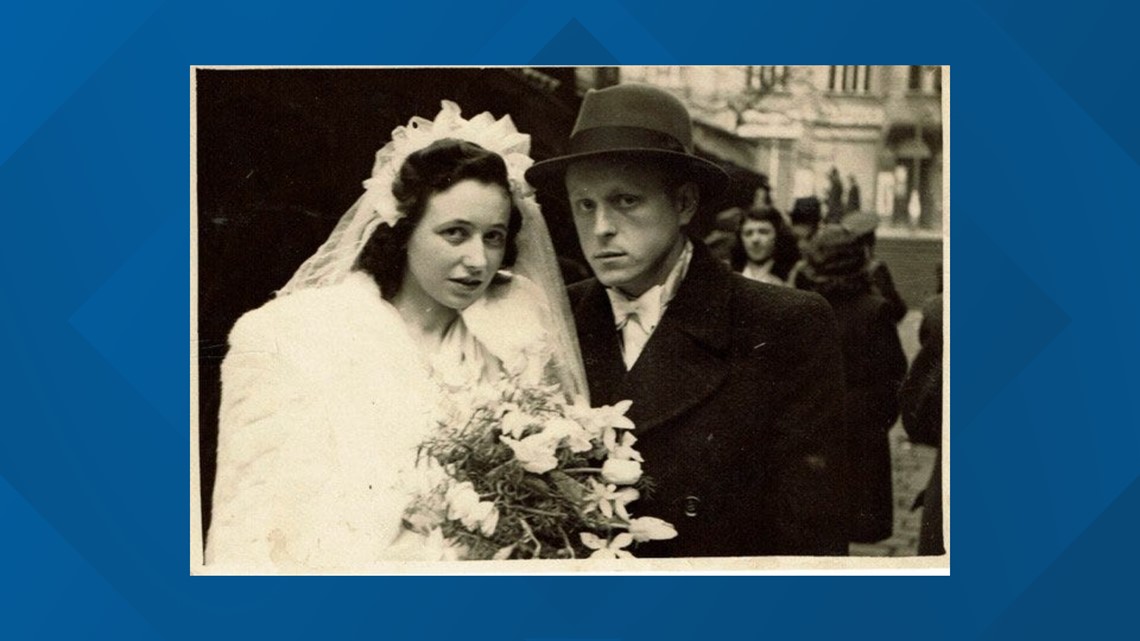

In 1946 when Colb married Margaret Heimfeld, who he'd first seen wearing that red dress, it was a happy occasion, but there was something missing. There were no parents there. They were all dead.

"What kind of wedding is that?" said Einstein, their daughter, who was born in 1947 shortly after her parents immigrated to the States to Cleveland.

Her father survived four years of hard physical slave labor, while her mother persevered as a slave laborer at an electronics plant. They were from the Carpathian Mountains, an area that was Czechoslovakia when they were born and is now the Ukraine.

In the United States, Einstein's mother worked as a dressmaker, while her father was a bookkeeper who went to law school at night to eventually get his degree. He was proud of being a lawyer and loved to joke: "So sue me!"

In 1985 they moved to Israel where their son had settled. Life was good, but the memories of what they went through stayed with them.

"They had a good life, a prosperous life, a secure life, and they were happy, my parents really were a happy family," she said. "But it was never gone ... there was always that fear that it could happen again."

Einstein became a legal aid lawyer in Waycross, Ga., and then Jacksonville, representing low-income people.

“I really see that as continuity with my father," she said. "You just have to think about the people in society who don’t have something, who are oppressed, who are taken advantage of. It’s unbelievable, the things people and companies would do to my clients because they had no power to fight back.”

'Really fearless'

The life of Post's mother, born Anna Dula, could have become a movie.

After the Nazi invasion of Poland, she lived in the open without wearing the Jewish star required of people of her faith. Twice she journeyed into the Jewish ghetto in Krakow to deliver food; on the second trip she was captured on a train, and villagers paid for her freedom.

Eventually captured again, she was able to persuade her Nazi interrogators that she was Catholic. She loved music, so she had gone to Catholic churches to listen to the hymns. That didn't prevent her from being transported to Auschwitz, where many Polish Catholics were taken, but it meant her chances for survival were better than if she were known to be Jewish.

To survive, she trained herself not to respond to Yiddish and to not speak the language. By war's end, she could no longer speak it, Post said.

To get to Auschwitz, she suffered through a sadistic three-day trip, packed in a cattle car with many others. That's where she made space for an older woman to be able to sit down. Later that woman, who worked in the camp kitchen, recognized her and got her a kitchen job too.

That probably saved her life, Post said. At that job, she could sit down while working. She had a support system. And she could manage to eat a little extra food herself — while still smuggling potato peels in her pants to feed to people in the barracks, risking a bullet in the head for doing that.

As the war came to end, she survived a long winter march toward Germany with other prisoners. One day, the Germans were gone, the prisoners abandoned. Anna made her way back to Poland, where almost everyone she knew was dead. Of her large family, only a brother survived.

Post knows why she made it: “Luck and youth and physical vigor and an incurably optimistic disposition.”

His father, Jacob, had been sent to a slave labor camp, but then — Post isn't sure exactly how it happened — he found relative safety as a worker at Oskar Schindler's enamel factory in Krakow. That didn't last though, and he spent the rest of the war in labor camps.

“People were being worked to death, literally," Post said. "But you had a chance for survival because they weren’t trying to exterminate you immediately.”

In 1957 Jacob and Anna Post immigrated to Israel and then five years later came to Buffalo, N.Y. He opened a wholesale business and she became a kindergarten teacher.

Louis Post, who lives in St. Augustine and turns 73 this month, is a retired psychologist. He said his parents were perhaps not visibly damaged by what they went through: They socialized, had a beautiful home, had friends.

“They weren’t fearful," he said. "They had true balls — they really were fearless.”

Inside them, it was a different story. His mother — who now has mild Alzheimer's disease — had nightmares in which Nazis would come and murder her children. His father, who has passed away, was never very trusting and became deeply suspicious of people he didn't know.

Post said he feels deep sorrow for them, for their massacred families, for an entire community he would never know. It was a world that was just "chopped to death."

'Curing myself'

After spending his teen years in Nazi concentration camps, Henri Landwirth had nightmares and sleepless nights, and found it hard to trust people. Still, Landwirth, who died in 2018, spent much of his time giving back, especially to sick children and the homeless.

He saw himself in them, said daughter Lisa Landwirth Ullman. She's 59, an interior designer who also ran the family's foundation for 15 years and helped start a program, Art With a Heart, for hospitalized children.

"He figured out a way to make it through life with all the trauma, his scars and wounds," she said.

That's just what he said in the documentary "Borrowing Time" that was made about his life and work. "That is my way of curing myself," Landwirth said on camera. "That is my therapy."

After the war, Landwirth moved to New York with an aunt and an uncle. Of his immediate family in Europe, only his twin sister, Margot, survived the Holocaust.

He met his wife, Josephine Guarino, at a wedding in New York. She was part of a big Italian-American family, and that was one reason he was drawn to her, Ullmann believes.

"I think my dad fell in love not only with her but her family, in that sense of belonging again,” she said.

The couple later moved to Florida where Landwirth found a lucrative life in the hotel business. They each lived into their 90s. After his horrific teenage years, Henri Landwirth's life was long, and satisfying and rich.

He devoted the last 10 years of his life to speaking in schools, his daughter said, imparting his thoughts on life and survival.

Ullmann, through the Holocaust Memories program, is now carrying that on.

"I feel like I'm walking into some very large shoes," she said. "More than ever, I am ready to tell this story, so it won’t be forgotten."