JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — By 1862, America had torn itself as massive armies marched across farmlands and old roads, fighting in large-scale battles with casualty rates that continued to shock the country.

Yet, the most important battle for America's future that year was not along the Tennessee River or Antietam Creek, but the political battle between two of the era's greatest politicians: A folksy, backwoods Illinois lawyer who became president after getting only 40% of the vote and an eloquent and persistent runaway slave who became the greatest voice of the abolitionist movement.

In 1838, 20-year-old Fredrick Douglass posed as a free Black sailor in Maryland and took a train north to New York City and freedom, according to the National Park Service.

Douglass was self-educated, largely by his own desire to learn and his understanding that education was “the pathway from slavery to freedom,” according to an article by the White House Historical Association.

Over the next two decades, Douglass rose from a conductor on the Underground Railroad and frequent attendee to abolitionist meetings to a best-selling author, eloquent speaker and perhaps the most powerful voice in America's growing abolition movement.

In 1860, Douglass threw his support behind Abraham Lincoln for the presidency, despite Lincoln calling for slavery's restriction not abolition during the election. Still, Douglass said while he did not believe Lincoln to a direct benefit to the abolitionist movement, an anti-slavery president was an important step forward, according to the White House.

"What, then, has been gained to the anti-slavery cause by the election of Mr. Lincoln?" Douglass said after Lincoln's election. "Not much, in itself considered, but very much when viewed in the light of its relations and bearings... Lincoln's election … has taught the North its strength, and shown the South its weakness. More important still, it has demonstrated the possibility of electing, if not an Abolitionist, at least an anti-slavery reputation to the Presidency of the United States."

Like Douglass, Lincoln rose from relative obscurity to great power. Born in Kentucky and raised in the Indiana frontier, Lincoln was also a self-taught natural politician with a knack for eloquent speeches.

Yet, Lincoln and Douglass had very different views as to the most important issue facing the country. Douglass tirelessly argued for complete and immediate emancipation with full civil rights for both men and women, according to the University of Houston.

On the other hand, while Lincoln personally detested slavery, he merely called for its restriction believing slavery to be a Constitutional right to the states that had already established it, according to the Bill of Rights Institute.

By the time Lincoln entered the White House in Washington as the country's 16th president, seven states left the union to form the Confederate States of America with their own president and new capital in Alabama.

With Lincoln focused on preserving the union, Douglass found himself in the White House time and time again, seizing on the opportunity to tell Lincoln the best way to beat the South is to free the slaves, according to the White House Historical Association. Yet, their relationship was far from warm.

Douglass, though he had a deep respect for Lincoln, was frequently angered by the president's slow move toward Emancipation. He was outraged by the president's plan to resettle Blacks in Liberia or Central America, according to the White House Historical Association.

"...though elected as an anti-slavery man by Republican and Abolition voters, Mr. Lincoln is quite a genuine representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred and far more concerned for the preservation of slavery, and the favor of the Border Slave States, than for any sentiment of magnanimity or principle of justice and humanity," Douglass wrote in his newspaper.

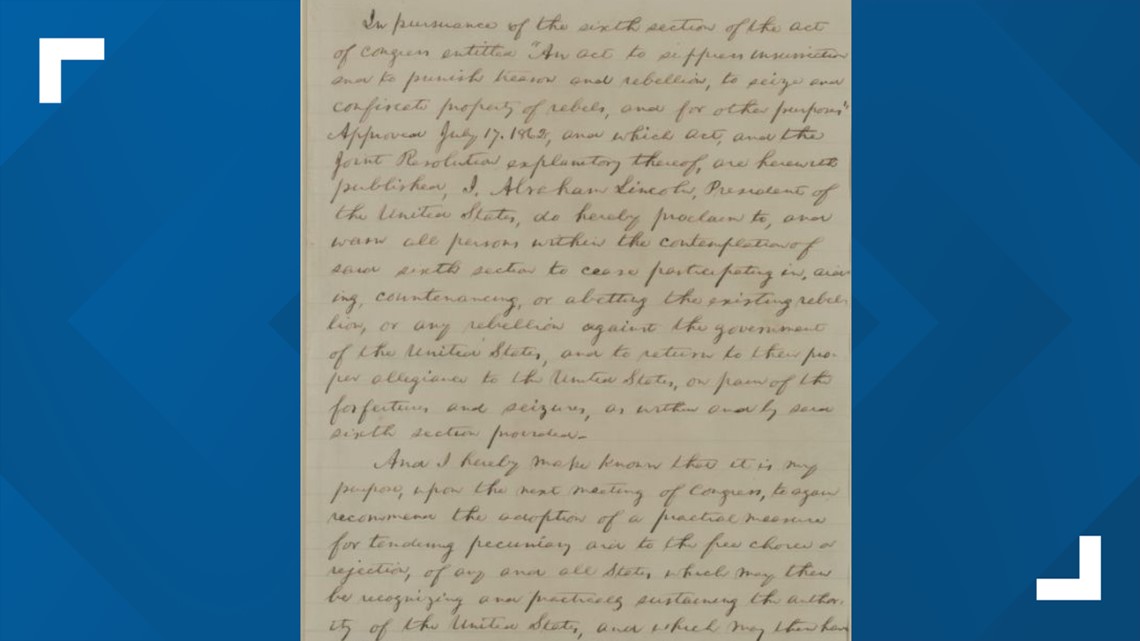

In the summer of 1862, with Confederate victories on battlefields in Virginia and with European powers poised to recognized Confederate sovereignty, Lincoln told his Cabinet he had decided to free the slaves in the southern states. While some members of the Cabinet were against the plan completely, others told Lincoln to wait for a decisive victory on the battlefield, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

That victory would come in September 1862 at Antietam in Maryland, ironically one of the few Union states that still maintained slavery. While America's bloodiest day was a tactical draw, the Union Army of the Potomac had stopped Robert E. Lee's invasion of the North, giving Lincoln the political opportunity to issue the Emancipation Proclamation on Sept. 22, 1862.

While the Proclamation did not guarantee freedom to a single slave, it both stopped England and France from intervening in the war, and would directly lead to Blacks having the right to fight for the Union, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

Yet, another major accomplishment of the proclamation was gaining the confidence of Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists.

"Abraham Lincoln is not the man to reconsider, retract and contradict words and purposes solemnly proclaimed over his official signature," Douglass wrote.

Still, Douglass, even in his gladness the proclamation had been made, criticized the president and his motives.

"It was framed with a view to the least harm and the most good possible in the circumstances, and with especial consideration of the latter," Douglass wrote. "While he hated slavery, and really desired its destruction, he always proceeded against it in a manner the least likely to shock or drive from him any who were truly in sympathy with the preservation of the Union, but who were not friendly to emancipation."

Following the proclamation, few worked as hard as Douglass to ensure what was promised was carried out. Douglass continued to tirelessly advocate for the total abolition of slavery and civil rights for those freed. Douglass also traveled south, helping to recruit two Black regiments, including the now-famous 54th Massachusettes, according to the White House Historical Association.

"The iron gate of our prison stands half open," Douglass said in his 'Men of Color to Arms!' speech. "One gallant rush from the North will fling it wide open, while four millions of our brothers and sisters shall march out into liberty."

Even when Blacks reached the battlefields, he fought for equal treatment and pay for the soldiers that enlisted to fight for their freedom. By war's end, Blacks made up 10% of the Union Army, and their valor had turned the views of many opposing Black men on the front lines.

In 1864, Douglass met Lincoln again at the White House. Fearing he may lose the upcoming election, and the Union would remain divided, the president asked Douglass how to secure freedom for the most amount of slaves possible, according to the White House Historical Association.

"What [Lincoln] said on this day showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had even seen before in anything spoken or written by him,” Douglass later wrote.

Their unlikely friendship was sealed when Douglass saw Lincoln the following year during the president's second inauguration, according to the White House Historical Association.

"There is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours," Lincoln said. "I want to know what you think of [my speech].”

Just over a month later, Lincoln was dead, killed by an assassin hoping to avenge the South's defeat in Virginia.

"Abraham Lincoln, while unsurpassed in his devotion to the welfare of the white race, was also in a sense hitherto without example, emphatically, the black mans President: the first to show any respect to their rights as men," Douglass wrote in a eulogy for the president.

In 1876, Douglass reflected on Lincoln and his seemingly paradoxical view of Blacks.

"...though the Union was more to him than our freedom or our future, under his wise and beneficent rule we saw ourselves gradually lifted from the depths of slavery to the heights of liberty and manhood," Douglass said in his speech. "Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined."

So honored was Douglas by the Lincoln family that he received the president's favorite walking stick as a gift.

After the Civil War ended, Douglass continued to lobby for civil rights, credited as being an important figure in the passing of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, according to the National Park Service. All the while, he became the most powerful Black politician in the country. He served in various federal roles under five presidents, even when the end of Reconstruction scaled back much of the work for which Douglass had dedicated his life.

He published a third autobiography in 1881, which not only discussed his life, but the work left for future generations after him.

In 1895, just weeks before Frederick Douglass died, a young Black activist asked the elderly Douglass what he should do with his life.

"Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!" Douglass replied.

More than 150 years after they first met, both Lincoln and Douglas are almost among the most highly respected and most honored Americans in history. Though Lincoln was posthumously given the title as the 'Great Emancipator,' it was Douglass, perhaps more than anyone else, who helped change the nation's Civil War from the preservation of Union to the fight for freedom, a fight that continues generations later.