TAMPA, Fla. — Florida’s indelible chapter in the Civil Rights Movement is heavily marked by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s presence in various parts of the state throughout the 1960s as he worked to defeat segregation, racial violence and the system that created both.

From the historic halls of the University of Miami and Miami’s Hampton House to a Southern Christian Leadership Conference Campaign in St. Augustine, that led to the passage of the 1964 Voting Rights Act, Dr. King used the blatant racism exhibited throughout the state to highlight the nation’s need for sweeping, immediate change.

How Dr. King’s time in Florida helped pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Florida’s role in the Civil Rights Movement is often overlooked, but the racial tensions and violence that played out while Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spent time in St. Augustine helped spur the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

"Dr. King was very focused particularly on St. Augustine, and its juxtaposition of being the country's oldest city dealing with the country's oldest sin...in terms of the racial injustice and racial violence that was occurring in St. Augustine,” said Earl Johnson Jr. of Jacksonville.

Johnson’s father was an attorney for Dr. King in St. Augustine. He said Dr. King contacted him as he and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference strategized a campaign to shine a light on the racism within the city.

According to The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, the goal of the campaign was to “lead to local desegregation,” and Dr. King hoped that media attention would garner national support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was then stalled in a congressional filibuster.

“Dr. King became particularly aware of the area and what was happening and we're talking about not just benign, Jim Crow, we're talking about racial violence happening,” said Johnson, who also referenced the Ku Klux Klan’s heavy influence in the area at the time.

“This was an area where black folks were absolutely oppressed,” he said.

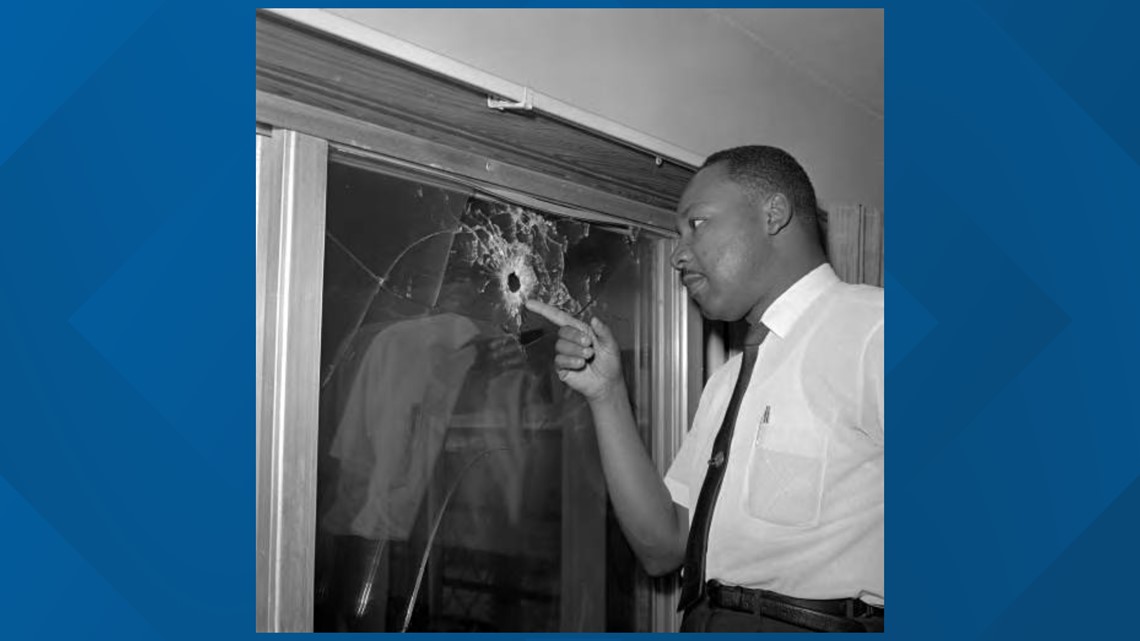

At one point during Dr. King's time in St. Augustine, a rented home where he stayed was targeted with gunfire. He was not home at the time.

He was also arrested while trying to get served at the Monson Motor Lodge and also faced charges of civil disobedience. He and his attorney took action.

“They actually filed a federal lawsuit alleging that the sheriff's office did not protect the protesters, who many of them, [were] beaten savagely by small mobs of white men,” said Johnson.

“Dr. King, going to St. Augustine, it helped because of his prominence, it helped really focus attention on the difficulties that were being faced in the movement,” said Rodney Kite-Powell, a historian at the Tampa Bay History Center. “…It really put a bad light on Florida.”

Dr. King understood that the May and June demonstrations in St. Augustine would call attention to why the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was necessary.

Images of attacks, like the iconic photo of the owner of the Monson Motor Lodge pouring acid into a pool of Black protesters, helped move the act forward.

Photographers captured a triumphant Dr. King making the peace sign with his fingers after the Senate passed the act in June. The peace sign, which also looks like a "V," is said to have stood for victory.

President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law on July 2, with Dr. King present.

“…So, Florida, and St. Augustine, our nation's oldest city, played a pivotal role in moving — not only bringing attention to some of the vicious practices of Jim Crow in the south but also in moving forward the important federal legislation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” said Johnson.

A King’s Miami

Dr. King also spent a significant amount of time in South Florida working to advance civil rights.

“I think Florida’s presence in Dr. King’s story is overlooked often because what we tend to forget…that South Florida and Florida, in general, is a part of the South,” said Malcolm Lauredo, a historian at the Coral Gables Museum.

“It's almost seen as this alternative…existence outside of North and South,” he said. “And I think that that sort of erases a lot of the issues that Floridians, that Black Floridians, have faced and the fights that they had to fight and the oppressions that they had to endure.”

Like other southern cities, segregation was the law of the land. In Florida, where even beaches were segregated, it was also the law of the sand.

“When Dr. King arrived in Miami, he surely found in many aspects and in many quarters of Miami, it to be an inhospitable southern town,” said Lauredo.

Throughout the early 1960s, Dr. King was a frequent visitor to the historic Hampton House hotel in the Brownsville neighborhood of Miami. It was one of the few hotels where Blacks could enjoy upscale leisure free from the worries of racism and oppression that ruled most hotels in the city.

An iconic photograph captures a relaxed Dr. King in the pool at the Hampton House, showing a side of the civil rights leader not often seen.

Well-known leaders and celebrities such as Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Sammy Davis Jr. and Duke Ellington also frequented the hotel.

Historians believe Dr. King gave an early version of his famous “I Have A Dream” speech at the Hampton House. He’s said to have delivered varying versions in different places across the nation well before the March on Washington.

“His speech grew as did his idea of what a better future looked like. So, I think Dr. King had an incredible impact on the civil rights movement in Florida, and I think Florida, as well, had an impact on Dr. King and shaping his vision of what's wrong with America and what we can do to find a better country,” said Lauredo.

King also spoke in March of 1966 at the University of Miami. Lauredo said his speech focused on the role of the church in fighting against racism and for equality.

While the speech was recorded, it for years had been lost to time. A snippet of the video recording was recently discovered in 2016.

In the short clip, he said:

"...[it’s argued] the Negro is a criminal. He has the highest crime rate in any city. The arguments go on ad infinitum. Then individuals who set forth these arguments never go on to say that if there are lagging standards in the Negro community, and there certainly are, they lag because of segregation and discrimination. They never go on to say that criminal responses are environmental and not racial. Poverty, ignorance, social isolation, economic deprivation breed crime whatever the racial group might be. And it is a torturous logic to use the tragic results of segregation as an argument for the continuation of it. It is necessary to go back to the causal basis and deal with that."

His visit was a controversial one at the time as he was receiving criticism for voicing opposition to the Vietnam War. According to the University of Miami, King was brought in through the back door of the Whitten Student Union out of concern for his safety.

Visits to Tampa and Central Florida

Throughout the early 1960s, Dr. King also made trips to Tampa and Orlando. In November 1961, he spoke at the Fort Homer Hesterly Armory on North Howard Avenue to a crowd of more than 4,200 people.

"Martin Luther King. Oh boy, we definitely wouldn't have missed that,” said Doris Ross Reddick, 94. She was in attendance the day of the speech.

While the Black community welcomed his visit to the Armory he wasn't welcomed by all.

"There were a lot of people, obviously, a lot of white people, who accused him of being a communist, who said that he was, you know, a racial agitator that he was making things more difficult rather than things better,” said Kite-Powell.

That resistance became obvious the night of the speech.

"There actually was a bomb threat that was called in...” said Kite-Powell.

10 Tampa Bay reporter Emerald Morrow made a public records request for the police report from the bomb scare and learned there were actually two threats called in. The first came at 8:05 p.m. and stated that a dispatcher received a call from a man that “sounded like a white male” that a bomb had been placed at the Armory.

The FBI was notified two minutes later. The building was vacated and a search for a bomb came back with nothing. About a half hour later, another bomb threat was called in.

"It was a kind of a frightful experience, but it was one that I wanted to be a part of, I suppose,” said Reddick. “…I've always dealt in activities that were a part of Black life. I am Black."

The program eventually continued, but there's not much left that tells what he talked about that day.

"It's a real shame and you know, we look back from our own perspective and think, 'how was that not recorded?” said Kite-Powell.

A program, a few photos, a short article and fading memories are all that remain.

"There were only I think two TV stations in the area — neither one of which was really covering a whole lot of positive African American news at the time. And so, they probably didn't bother to send anybody,” said Kite-Powell.

A book holding the papers of Dr. King says he was interviewed while traveling from Tampa International Airport to the event. However, there's no record of that either.

"You have oral histories of people who were there, and Dr. King was giving very similar speeches. He didn't just come to Tampa, and then go back home. He traveled throughout the South at that time, and so Tampa was one of several stops,” said Kite-Powell.

Reddick says at 94, she can’t remember specifically what he talked about, but said she remembers the general message he gave.

"The general message was...that we had to do whatever was necessary to make progress,” she said.

A short article from the Tampa Tribune says Dr. King talked of a "new order" and that "we are standing on the border of the promised land of integration." A timely message for a segregated Tampa.

"We're 10 years away from full integration of the public school system in Hillsborough County. Neighborhoods still very segregated...” said Kite-Powell. "You're still decades away from Black representation on the city council and county commission, school board. And so, there are still a lot of gains to be made."

Something Doris Reddick says is still true today: "Oh, yeah, we do have a long way to go."