Like a lot of Puerto Ricans, Nancy Quinones left the island a professional and arrived a virtual pauper.

Without English, she says, her training as a pharmacist was worthless.

“You can be biggest professional in Puerto Rico, you can be an engineer a pharmacist,” says Quinones, whose first job was a short order cook. “But if you don’t speak English, you are nothing.”

Nancy mastered English. And, as head of the Jacksonville PR Hispanic chamber of commerce, hers can be considered a success story. But it’s just one story in what has become one of the largest mass migrations in U.S. history.

Cubans have long been one of the defining demographics of the Sunshine State. But they will soon be eclipsed by another Hispanic population. The number of Puerto Ricans leaving the island and moving to the United States has surged by 75 percent in the past decade, and is now nearing 1 million. Some 45,000 alone live on the First Coast.

Dr. Fernando Rivera is a demographer and sociologist at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. He’s also a Puerto Rican native, and part of a diaspora that has drained the island’s population by nearly 15 percent in 10 years.

“We’ve got more Puerto Ricans living outside of Puerto Rico than in Puerto Rico,” he says. “Outside of a major war or humanitarian crisis that’s a huge population loss.”

Rivera has a unique view of why so many choose to move to Florida – particularly the area around Orlando. “I call it the Disney effect,” he says. With trips to Disney World “a virtual right of passage” for Puerto Ricans, Rivera says they often mistake conditions there for a typical existence on the U.S. mainland.

“They think: my hotel was perfect, everything was so clean, everyone was so friendly,” he laughs.

Reality is grimmer.

“They don’t have money for rent, so they end up living in neighborhoods that may not be safe. You end up doing cleaning work at Disney.”

Still, leaving is often feels like the only option. The Puerto Rican economy is in free fall, the government swimming in more than $70 billion in debt, and unemployment is surging.

The crisis is a byproduct of excessive bond and pension debts, government corruption, and the end of attractive subsidies that once made the island home to the profitable pharmaceutical industry. The result is an economic spiral that is like Detroit – only worse. Unlike Detroit, Puerto Rico is legally prohibited from restructuring its debt by declaring bankruptcy.

“Those things accumulated to the point of no return – which is now,” says Rivera. “People have been saying for years, there’s no money. But now come to reality that: there really is no money.”

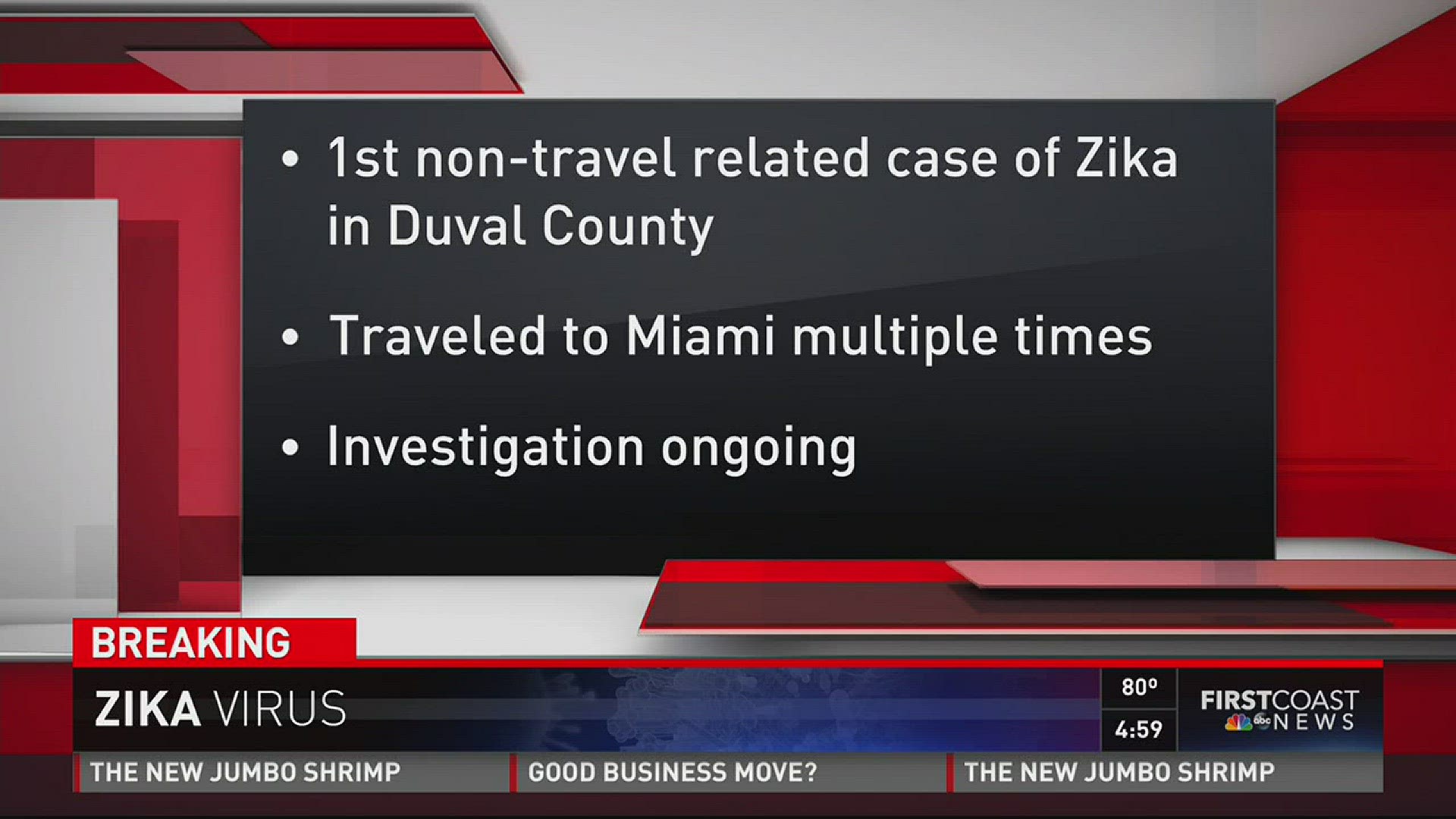

A bill passed by Congress in June establishes a 7-member financial control board that is expected to implement austerity measures and rein in island finances. In the meantime, the economy has made fighting the Zika virus more difficult, which in turn has impacted tourism – a kind of perfect storm that Quinones says will have impacts for generations to come.

“They get separated from their family,” she says of the thousands fleeing each month. “The young people are leaving; the traditions get lost.”

And the arrival, as she knows all too well, isn’t always smooth. Of her first mainland job, she recalls, “I spent one and a half years crying in that kitchen.”

“It’s been hard,” says Rivera. “It comes with a human toll. It comes with a human sacrifice.”