JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Army Staff Sgt. Jerry Majetich has spent his life serving, first in the United States Marines, then in the United States Army.

Now he is serving in the world of science and research.

“There were eight insurgents that were waiting for me," Majetich said. "When my vehicle ran over the roadside bomb, they triggered it.”

A 2005 ambush in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom left him with a traumatic brain injury, severe burns and countless injuries.

Two months later he woke up in a Texas hospital and learned his new reality.“I was burned over 37% of my body, 100% my face and scalp,” Majetich said.

That was just the beginning of what would be years of surgeries. He recently had his 82nd operation.

“The hardest thing to adjust to, and I have adjusted, it’s been 15 years plus, is people's reaction to my physical appearance,” Majetich said.

While surgeries have helped improve his quality of life, his right hand, mangled in the blast, remained a source of constant, blinding pain.

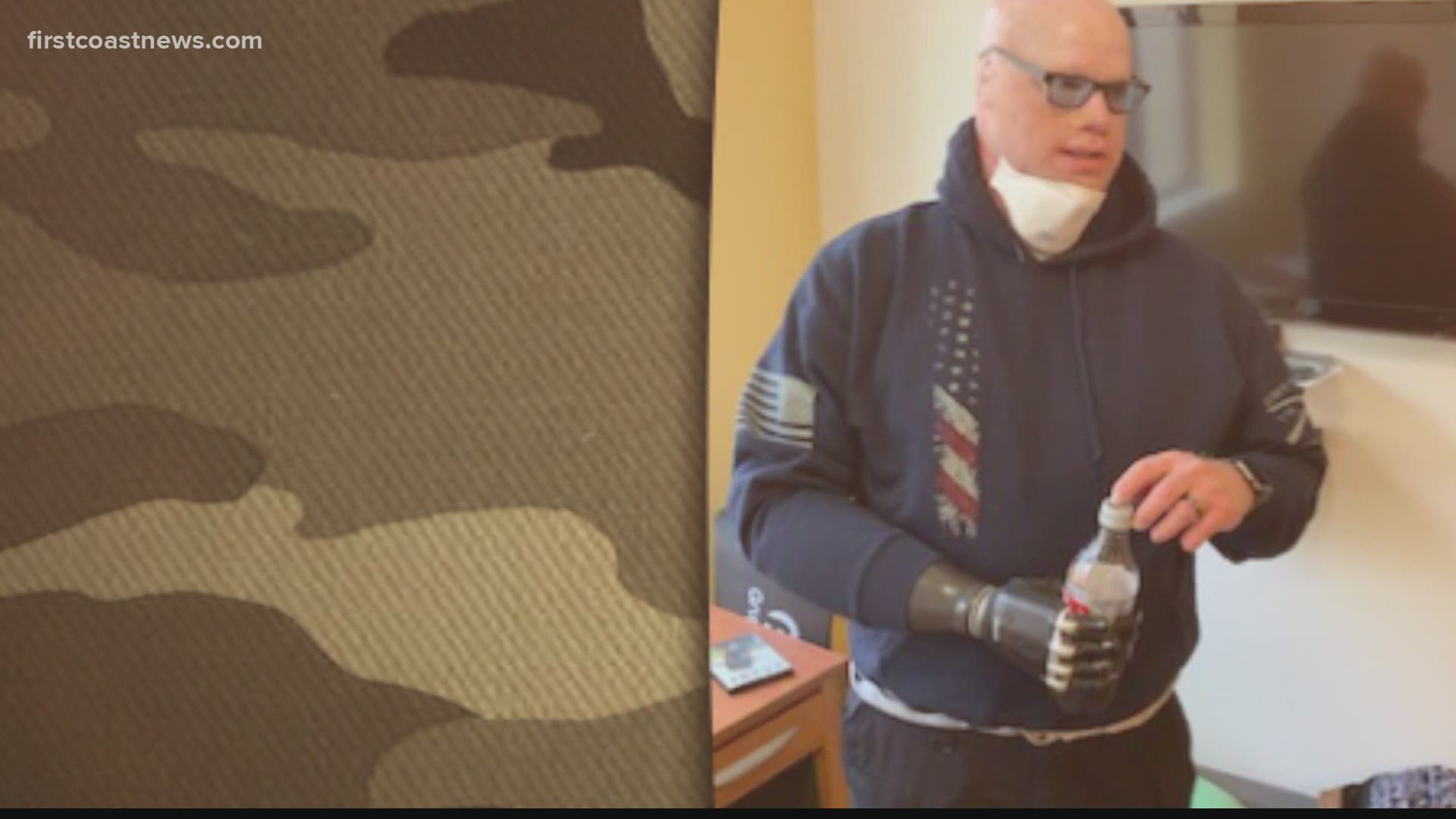

Last summer, he made the difficult decision to have it amputated.

“The hand was collapsing, and the last surgery was 17 and half hours, but it failed," Majetich explained. "And I asked them to please take it at that time because it was just causing too much pain.”

It was no ordinary amputation. Majetich volunteered to be the first person in the world to have an experimental surgery on an upper extremity using what is called the AMI procedure.

Dr. Scott Tintle, Chief of Hand Surgery at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, and plastic surgeon Dr. Jason Souza amputated Majetich’s hand.

“Jerry agreeing and volunteering to try to push the science forward has been just one more sacrifice that Jerry's made,” Dr. Tintle said

His surgeons at Walter Reed rewired his nerves, so they have somewhere to go and something to do instead of just causing pain.

“The thing that was unique about Jerry’s surgery is we've taken it to the next step, which is to try to reconnect the tendons to essentially reconstruct the wrist joint, and the finger joint on the end of his residual limb, on the end of his amputation stump, to try to give him a better sense of control,” Souza explained.

The surgery had previously been performed on lower extremities, but never on an arm.

“The team up at Brigham and Women's is doing more and more of these, and so it's moving out of the experimental realm to a more conventional technique," Souza said. "But it takes patients like Jerry to enable us to try to innovate, but then also understand it.”

Majetich is now enrolled in a research project at Walter Reed, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and MIT. His surgeons say it’s a team approach and collaborative spirit that is helping advance the science.

“If you look at Jerry’s surgery and the number of surgeons who have come together to kind of think about his case and to actually execute his case, and then the rest of the team and how closely integrated the therapy team, the prosthetics team, the pain management team, the rehab team are, I think that's really the model that you need to try to push the envelope,” Souza said.

Dr. Tintle said the surgery has been a success.

“Thus far, it's been fantastic," Tintle explained. "In terms of Jerry's pain control, he has been sleeping better. From his wife, it seems like he's the happiest he's been in 10 or 12 years, and his pain is really, really decreased."

This innovative approach has the potential to revolutionize the world of prosthetics.

“The technology is getting closer to just actual hand movement based off of your thoughts versus what you're doing in your arm,” Majetich said. “But for me, the pain, the pain, there's no pain. The pain being gone is has changed my life.”

His doctors recreated a pulley system in his arm using parts from his wrist to provide a signal back to his brain.

“When you flex your hand, the muscles that are that extend the hand are being stretched, right? And what happens is your brain gets a sense of where your hand or where your wrist is in space, because they know what muscles are being stretched and which muscles are flexing,” Dr. Souza explained. “What we did is essentially restore that relationship.”

The hope is that this will help alleviate phantom pain.

“With this entire approach to amputation, we have fairly lofty goals, but we don't know what's realistic,” Dr. Souza said. “What Jerry is offering us is an ability to actually understand how this benefits him.”

His doctors believe it will lead to better prosthetic function.

“His fingers on the inside of his forearm actually work like our fingers do except they're internal,” Mary-Ella Majetich explained. “When a prosthetic with electrodes goes over those fingers, he can move the fingers and he has more points on his forearm than a typical amputee would.”

Majetich’s credits his wife whom he married five years ago, with helping him realize he didn’t have to be resigned to a life of pain.

“She helped me through the process of going back to the doctor and getting the help that I needed when I'd given up on everything else,” Majetich said.

Hope is a powerful medicine, and Majetich and his doctors encourage other veterans not to give up.

“If they've resigned themselves to a life of pain because of their limb, I just want there to be a sense of awareness that things have continued to improve over time, and that there continues to be innovation, and that we've now spent the last decade learning from people just like them who have been injured a decade or two ago. And we've continued to learn and innovate,” Souza said.

Majetich is grateful this surgery has led to pain relief for him, but he is more focused on how it will help others.

“I am thankful for the opportunity to help the veterans that follow because you know, there are there will be other wars, there'll be other amputations and I want to make sure that things are better for those that fall behind me.”