JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — For months, it’s been a mystery: Why Jacksonville city sewage showed almost no trace of the novel coronavirus, despite the city’s high rate of COVID-19 infections.

The baffling results made the city an outlier, alone among hundreds of metro areas using sewage to track, predict and even prevent viral outbreaks.

But the latest results of a new testing method reveal virus levels up to 10,000 times higher than earlier samples – shifting Jacksonville’s sewage to the forefront of scientific research.

“We were able to solve the mystery,” said JEA consulting engineer Ryan Popko. “This was a really exciting finding, and may change how they end up sampling in the future.”

It will also change JEA’s testing program – or rather stop it entirely – while research catches up. Popko says the utility will put testing on hold while the lab determines just what the virus concentrations mean, and how they compare to earlier data.

JEA began collecting sewage samples in May and sending them to the University of Arizona for testing. For the first several months, the results showed barely detectable levels of the virus: just four of 36 samples had even a trace presence. JEA officials wondered if the sheer size of the city's sewage system was to blame. They tried sampling “upstream” closer to the source (i.e. customer’s homes) -- without success.

So last month, the lab tried a different approach.

“They analyzed the sample a little bit differently, where they targeted the solids that were in the sample rather than just the liquid,” Popko said. “Compared to the levels we had detected previously, this is on the order of 1000 or 10,000 times higher.”

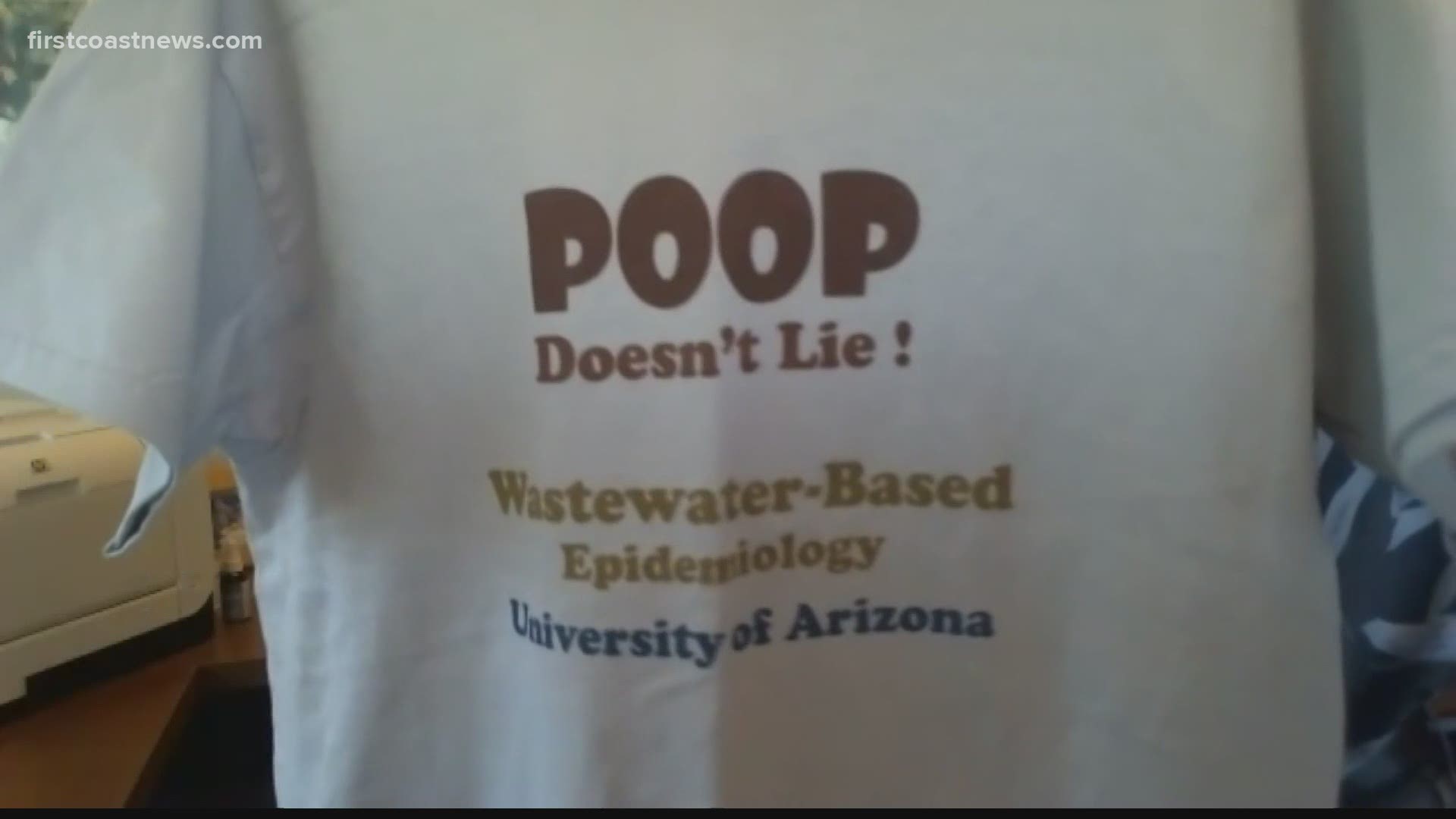

“Poop doesn't lie,” explained Dr. Ian Pepper (yes, Dr. Pepper) an environmental microbiologist who runs the wastewater research lab at the University of Arizona, and is at the national forefront of sewage testing for the coronavirus.

That indelible quote has become Pepper’s trademark. He even made T-shirts with the message. But it’s never been more true than with the recent JEA test results.

“This is actually an exciting finding because actually processing the [solids] sample in this way is quicker than the other way we were doing it,” said Pepper. “So shorter time needed for testing.”

Pepper still does not know why JEA’s liquid samples showed no results. “All I can tell you is that we have ran 300-320 wastewater samples from wastewater treatment plants from across the country and have not ran into that problem. So it's still a bit of a mystery.”

The science of sewage testing isn't new, having been used to track and contain the poliovirus, and it has great potential to combat COVID-19. Because people begin shedding the virus up to seven days before exhibiting symptoms, sewage can presage a spike of community contagion. Pepper used it with pinpoint accuracy on campus. After tests showed the presence of the virus in a single dorm, campus officials were able to locate two asymptomatic students and isolate them to prevent further spread.

Since then, campus testing has been implemented at several schools, including Notre Dame, Stanford and Michigan State.

Pepper said the world of sewage science has become an increasingly dynamic and esteemed area of research, particularly during the pandemic.

“It’s gotten greater respect. The name has changed from ‘sewage effluent testing’ to ‘wastewater-based epidemiology.’ And really, you're seeing the birth of a new discipline. So in the future, you'll see students getting degrees in wastewater based epidemiology because you can also use it to look for new novel viruses. You can use it to look at the concentrations of illicit drugs, and from there, get an estimate of the number of people in the community that have taken that drug. And you can also look for food metabolites, and look at the influence of food insecurity. So there's a lot of different applications.”