Investigation: Why do 2 officers on the Brady List continue to work in Jacksonville?

Law enforcement employees who've been arrested or can’t be trusted are on the Brady List. Every Jacksonville officer on the list has quit or been fired, except 2.

The list is 76 names long, names of law enforcement employees in Duval, Clay and Nassau county who’ve shown bias, been charged with crimes or are considered dishonest.

They're on the list because they could be a liability if called to testify in a criminal case. Some have been arrested for DUI or domestic violence. Others tampered with evidence, were accused of lewd acts or even smuggled drugs into jail.

Most of the officers are long gone, having quit or been fired.

But two Jacksonville Sheriff's Officers remain on the list -- and on the job.

Credibility Issues "That's a big deal"

There wasn’t always a list. Former State Attorney Angela Corey didn’t keep one. It wasn’t until Melissa Nelson took office in 2017 that the list became available.

Not that it’s widely available. Officers on the list – from Clay, Duval and Nassau counties -- are revealed to defense attorneys only when they are directly involved a case. Some attorneys don’t even know the list exists.

The list is a byproduct of a 1963 Supreme Court ruling, Brady v. Maryland, requiring prosecutors to turn over any potentially exculpatory evidence to the defense; and Giglio v. United States, a 1971 case that established similar rules for witnesses with a history of dishonesty.

It’s known as the Brady/Giglio list.

The very existence of the list troubles the police union, which believes it unfairly tarnishes the reputation of some officers. The local Fraternal Order of Police has pushed the state attorney to create an appeal process to give officers a chance to challenge being on the list.

It also troubles some in the community, who question why an officer on the list continues to work a beat.

Only two local officers on the list remain on duty.

JSO Officer Aaron Roe is on the list because of a 2018 DUI, in which he ran a red light and nearly hit a median, according to the arrest report. He pleaded no contest, so was adjudicated guilty and placed on probation.

Sgt. J.C. Nobles has a more complicated backstory. In his nearly 20 years with JSO, Nobles has accumulated 65 discipline complaints. He has the third-most complaints of any officer, and the most unnecessary force complaints of any officer, according to a 2018 analysis by First Coast News.

He has also been involved in five officer-involved shootings -- more than any other active duty officer, according to available records.*[1]

All of his shootings have been deemed justifiable by the State Attorney’s Office.

But Nobles isn’t on the list because of these statistics. He’s on it for serious questions about his credibility.

In a 13-page order written in 2018, Circuit Judge Bruce Anderson said he found Nobles “specifically not credible.” He said the sergeant “did not seem to have an accurate memory,” was “evasive, confrontational, argumentative and non-responsive during cross examination.” And because he found that Nobles “completely and materially changed his sworn testimony,” the judge threw out the case.

Nobles did not respond to two interview requests made through JSO’s public information office, but in a related Internal Affairs investigation, he said he got confused during his sworn deposition and inadvertently gave incorrect testimony. The fact he changed his testimony at a hearing a year later, he said, was an effort to correct the record.

The case in question started with a traffic stop. According to the police report, Nobles and another officer stopped 21-year-old Marquis Jackson in August 2016 for failing to wear a seatbelt, running a stop sign and almost “T-boning” Nobles’ police car.

In his deposition, Nobles described in detail the intersection where it occurred, including the direction and position of both vehicles. He even drew a map.

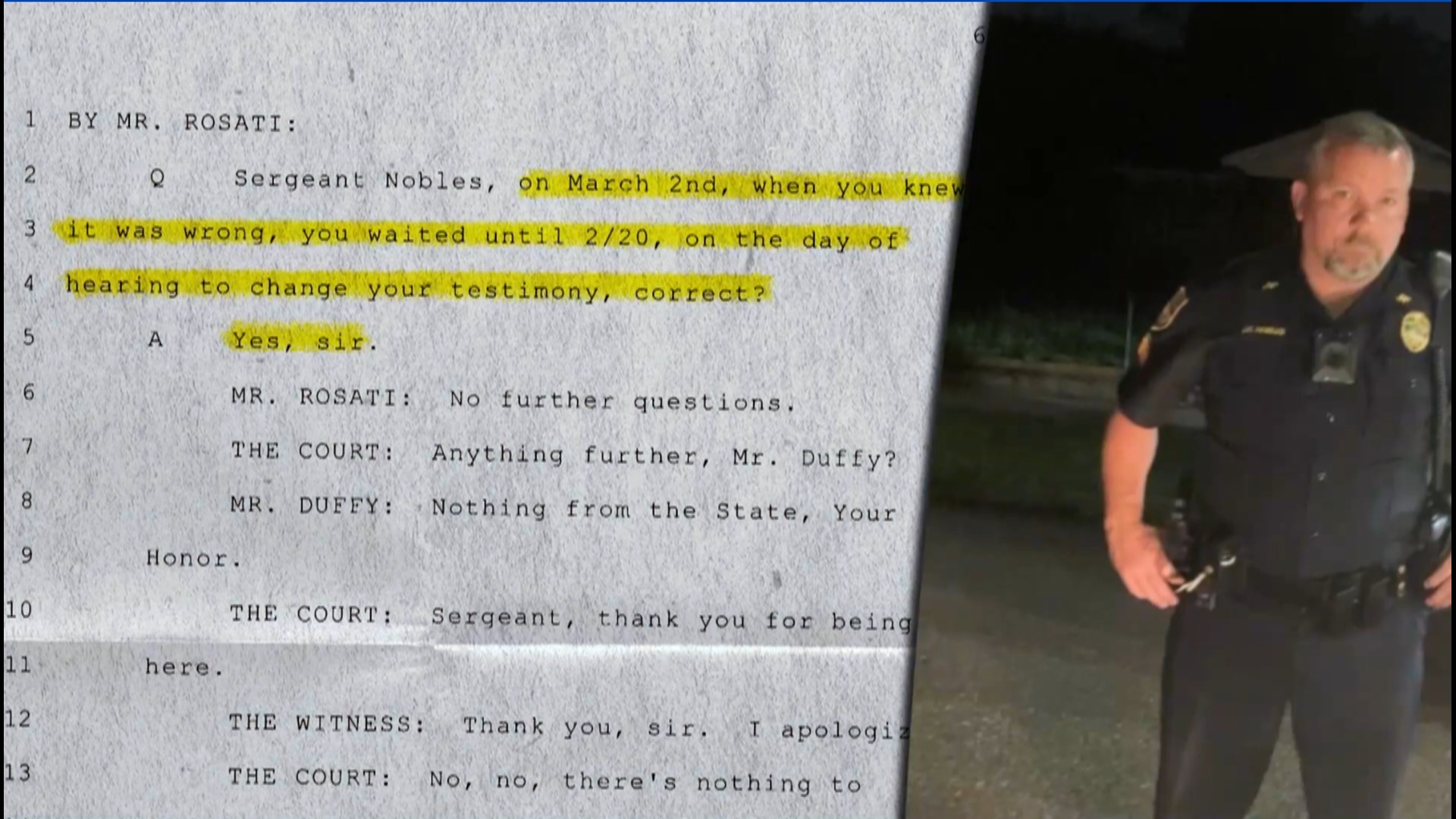

But Nobles changed his testimony at a suppression hearing a year later. When defense attorney Anthony Rosati pointed out he couldn’t have seen a seatbelt violation or nearly been “T-boned” in the scenario he described, Nobles said, “I made a mistake.”

Nobles suggested he was unfamiliar with the area near 63rd Street where the traffic stop occurred. “I’m assigned Downtown, and when you go up there, which is several miles north, I just – I got confused on my directions.”

As for the map he’d drawn, complete with arrows and cardinal points, he said, it was just wrong.

“His whole story was based on going eastbound,” Rosati told First Coast News. “[If] he's going westbound, the traffic stop goes away. So he had to change the story.”

Nobles told the judge he realized his testimony was wrong “right after the depo,” but didn’t attempt to correct it until the day of the hearing, nearly one year later.

“That’s like one of those ‘Matlock’ moments,” said Rosati. “I was like, ‘What!?’”

The fact Nobles didn’t correct his testimony, or even notify the prosecutor he'd erred, “That's a big deal,” Rosati said. “You waited a year?”

At the hearing, then Assistant State Attorney Declan Duffy maintained that Nobles was genuinely “mixed up” when he drew the map. But he conceded that the judge would have to make his own determination.

“It is pretty much a credibility issue,” Duffy told the judge.

"It’s entirely” a credibility issue, Rosati enjoined. “There is enough on this record to show that Sgt. Nobles is not credible in his memory, his recollection, his testimony, his demeanor, everything.”

Rosati asked the judge to suppress all evidence in the case, including drugs and guns found in the car, saying it flowed from an illegal traffic stop and the word of an unreliable officer.

“He’s a sergeant, Judge,” Rosati added. “I don’t believe it, and I’m asking the court not to believe him.”

The judge didn’t believe him.

“The court finds that the testimony of the officers in general, and Sgt. Nobles specifically, was not credible,” Judge Anderson wrote. “The court concludes that it will not believe the ‘corrected’ testimony of Sgt. Nobles.’”

Why are they still employed? “He got confused, plain and simple"

“Extraordinarily unusual, and extraordinarily courageous.”

That’s how veteran defense attorney Tom Bell characterizes Judge Anderson’s order.

"In 35 years, I don't think I've ever seen an order where a judge just expressly finds the officer’s testimony can't be believed,” he said.

“That's a huge deal in the legal community,” agreed attorney Melinda Patterson. “That's [over] a 10-page order on how Nobles, specifically, is not credible, should not be found to be credible.”

Rosati agrees the order was significant, but said he’s been disappointed by how little impact it’s had.

“If an officer is on a Brady list, or doesn't have credibility, why are they still employed?” he asked. “Most officers take pride in their job, they have integrity outside the force, integrity on the force, and they do their job well. And they play by the rules. … But I’m not for any officer being on the force that's not doing their job correctly.”

Instead of being sidelined, Rosati observes, Nobles maintains the rank of sergeant and continues to participate in traffic stops.

“I’ll read a report and I'll say, ‘This sounds like, Sgt. Nobles.’ And I'm sure a majority of the defense bar are aware of his reports, too. When you start reading, it's like, wow, wow -- wow?! … wait a minute. Oh, it’s [Nobles].”

Chief Assistant State Attorney L.E. Hutton declined to discuss Nobles specifically, but agreed it’s unusual for an officer on the list – particularly for issues related to honesty – to continue working at JSO. “A finding of untruthfulness is -- typically, my experience is that that officer is either going to resign or be fired.”

Sheriff Mike Williams declined to be interviewed for this story. He also didn’t respond to 10 emailed questions, including whether he’s ever read Judge Anderson’s order or if being on the Brady/Giglio list affects an officer's assignment.

But Steve Zona, former president of the local Fraternal Order of Police, willingly stepped to Nobles’ defense. “If the chips were down, and I needed a police officer at my home, for my family, this officer would be the one I would want to come and help me,” he said.

Zona says Nobles changing his sworn testimony wasn’t a sign of deception, but of poor preparation. “He got confused in his deposition, plain and simple. And when he got confused, that's when he gave the incorrect testimony.”

Zona notes that Nobles’ revised testimony hearing actually aligned with the original incident report, which was written by another officer on scene. He believes that reinforces Nobles’ claim he was simply righting the record.

“If you look at the original arrest and booking report, written that night, almost a year prior to that officer giving testimony, is accurate,” said Zona. “Nobody talked about the arrest and booking report from the night of the incident. Not the prosecutor, not the defense attorney, not the judge. Nobody, not even our officer.”

In fact, according to the transcript, Judge Anderson did ask about it. “You’re saying that the arrest and booking report is accurate, but your testimony is not?” he asked. “Yes,” Nobles answered.

Judge Anderson did not respond to requests for comment.

As for the judge’s finding that Nobles was “not credible,” Zona scoffs.

“I'm not saying he's a horrible judge. … [But] I don't have faith in his ruling that that officer was not credible. And I think he's wrong.”

The man in charge "He's very aggressive..."

Biko Misabiko was a teenager when his family moved from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to Jacksonville. Now a community activist in Springfield, he says he’s personally been dealing with Nobles for 15 years.

“I paid my dues out on the street, but now I’m on the righteous side,” he said. “As a man, you always want to go and fix your errors. And that's where I'm at now -- going back and fixing my errors, the damage that I caused my community.”

Misabiko said that effort is complicated by Nobles, who he says has a reputation for being unnecessarily combative.

“This officer has a pattern of just mistreating people, just being rude. So whenever there's a stop, it ain't like, ‘Hey, what's going on?’ It's very mean. Very aggressive. He's very aggressive.”

He had his first encounter with Nobles at age 15. No police report was available to corroborate his memory, but he said it gave him an early awareness of Nobles' "ruthless" style of policing.

First Coast News spoke to several other men who lived in Zone 1, Nobles' former assigned zone. They echoed similar complaints, but declined to comment on the record. Three specifically said it was because they didn't need "a target on" their backs.

Misabiko has complained to JSO and the State Attorney’s Office, even started an online petition to get rid of Nobles (which has 5,200 signatures). But rather than seeing him sanctioned, he’s watched him move up through the ranks.

“He’s the Sarge, he’s the man in charge,” Misabiko said. “And the way he’s conducted his squad is the same way when he was out here when I was younger, how he used to treat us. And when I tell you this little fella is a tough, mean, just ruinous-- you know, just talking about it kind of angers me.”

This missing phone "He denied having the phone all three times"

It’s not just judges, lawyers and community members who have concerns about Sgt. Nobles’ credibility.

Some officers do too. In 2019, Officer Tamara Hardin initiated an Internal Affairs investigation of Nobles after he confiscated a juvenile’s cell phone at a crime scene, then denied taking it – three times, records show.

Body worn camera would later reveal that Nobles had the teen’s missing phone stuffed in his back pocket at the crime scene. But according to the report, when Hardin realized the phone was missing, she called Nobles to ask if he knew where it was. She said he replied, “Tammy, don’t worry about that phone.”

Hardin called him back a short while later to make sure. Again, the report says, he denied taking the phone.

“He denied having the phone all three times,” the report said, “and then in the middle of the third conversation advised he found it on the floorboard of his vehicle.”

Hardin* [2] told investigators she thought perhaps he wanted to “use the phone” to get information in another case. Nobles denied this.

“Nobles said he had no intention of stealing the phone,” the report said, “and did not try going through the phone for information.”

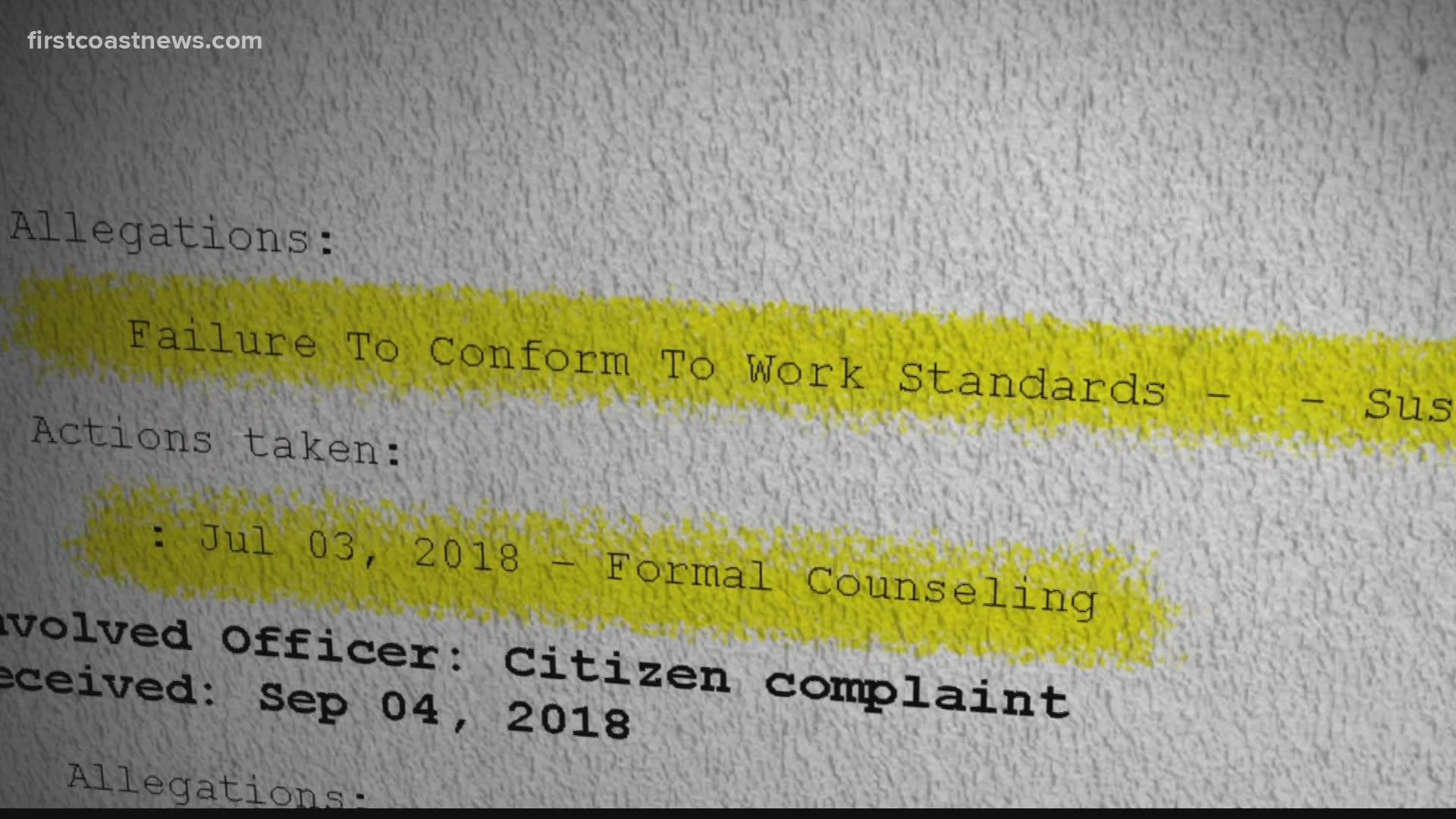

Investigators categorized Nobles conduct as a “failure to conform to work standards,” and he was given “informal counseling” as punishment.

Almost as an aside, investigators asked Nobles why he failed to activate his body worn camera during the arrest of the two juveniles, as required. “Nobles said it just slipped him mind,” investigators wrote. “Nobles was reminded that the BWC beeps and vibrates when on. Nobles said he just forgot.”

65 Complaints No records, little punishment

JSO destroys officer discipline records after just a few years.

Complaints deemed “unfounded” or “not sustained” are destroyed within a year. Complaints that are “sustained” but punished with only written reprimands are kept just three years. Even sustained complaints that result in an officer being suspended or fired are kept for just five years before being destroyed.

As a result, it’s impossible to know what prompted Nobles’ many discipline complaints, or why he’s received so little punishment. More than half of the 65 entries in his discipline database are allegations of excessive force, rudeness, or improper behavior.

Only 10 were “sustained,” meaning they resulted in punishment, and penalties were scant. During his 17 years on the force, his most severe punishment was meted out in January 2021, after he failed to show up for a scheduled wellness appointment. He lost the use of his take-home vehicle for 14 days.

Proactive policing Credibility is the 'central question'

Sgt. Nobles has made a lot of arrests. Asked to estimate just how many at a 2018 disposition, he said, “I wouldn’t begin to guess.”

Today Nobles is officially assigned to Zone 5 Patrol. But like his colleague in numerous arrests and one fatal encounter, Officer Tim Terrell, he frequently works secondary employment jobs, which are off-duty, and in uniform. That can mean providing police security for a private entity, like an apartment complex. It can also mean “proactive policing.”

Nobles and Terrell were doing both in April 2008 when they stopped a man for speeding on Lane Avenue South, at the entrance to Londontowne Apartments (now Riverbank). They ended up arresting the passenger, Jabarren Hansell, after searching the vehicle and finding a gun. (Terrell did not respond to interview requests made via JSO’s public information office.)

Hansell’s attorney, Tom Bell, filed a motion to suppress evidence taken from the vehicle, including the gun. He argued the traffic stop was a pretext for an illegal search, and he questioned the officers’ version of events. “The central question in this case,” he told the judge, “will be the credibility of these two police officers.”

Whether the jury had similar concerns about the officers’ credibility is impossible to know. But after several hours of deliberation over two days, they could not reach a verdict, and the judge declared a mistrial. Rather than retry the case, the prosecutor moved it to state court where the two sides reached a plea deal for about half the prison time that would have come with a federal conviction.

Probable Cause A conflict in testimony of officers

Anthony Rosati says his first experience with Nobles was a 2006 case he’d worked on with his then-law partner, Otto Rafuse. The defendant, Anthony Cruel, was well-known to cops and the streets. A convicted felon, he was shot in the leg shortly before his arrest, and shot in the face soon after. According to court records, it was difficult to understand his testimony because his lower jaw was destroyed.

Cruel was ultimately convicted. But Rosati says the case taught him to recognize what he calls hallmarks of Nobles’ cases: traffic stops for speeding, seatbelt violations, or failure to stop at a stop sign. In several cases, Nobles asserted the driver nearly “T-boned” his car. The stop would be followed by a vehicle search, and often drugs or guns were found.

Anthony Cruel had a gun in his car when Nobles and Terrell stopped him on West 16th Street that December night. They stopped him for a speeding violation. Terrell testified he’d been clocking motorists on radar as they left the Roosevelt Gardens Apartments complex, just north of UF Health.

The apartments are built on a cul-de-sac with a single access road, so Rosati says clocking drivers leaving the complex was odd. But it was the bedrock of Officer Terrell’s testimony. He said he’d been parked at the end of the access road when he registered Cruel doing 18 mph in a 10-mph zone.

That claim became problematic at trial, because the 10-mph zone started at the security gate. The street leading there was 30 mph.

It turned out Terrell had clocked Cruel doing 18 in a 30.

That didn’t derail the case, though, because Nobles had a pile of additional probable cause for the stop. He’d followed Cruel’s car out of the apartment complex and said he failed to use his turn signal at the end of the street, court records show.

When Cruel’s attorney pointed out that a signal failure alone isn’t sufficient probable cause for a stop, unless it impacts traffic, Nobles said it did impact traffic. “It almost caused a crash,” he testified.

Here, the officers’ testimony diverged so sharply that Otto Rafuse called it “an aberration.” Officer Terrell – with his radar gun trained on Cruel’s car – never mentioned seeing a near-accident. It isn’t noted anywhere in the police report. And Nobles never brought it up during an earlier deposition.

“He came in here and his testimony changed,” Rafuse told the judge. “Two different testimonies. One had to be perjured, there is just no two ways about it.”

Circuit Judge Charles Arnold wasn’t persuaded. He denied the motion to suppress. He conceded, “there’s substantial conflict in the testimony of the officers,” but said it was “a classic case of conflicting testimonies” and a matter for the jury to decide.

They found Cruel guilty, and Judge Arnold sentenced him as a habitual violent felony offender to 25 years in state prison, where he remains today.

Officer-involved shootings A closer look at the facts

Officer Terrell is not on the Brady list. He hasn’t been disciplined since 2017. But he is a frequent co-worker of John Nobles.

“We make arrests together all the time,” he testified in 2009. “We work together quite closely.”

The pair was working together in December 2006 when they arrested Anthony Cruel; in April 2008 when they arrested Jabarren Hansell; and in June 2009 when they shot and killed 24-year-old Kiko Battle.

According to police, Battle and a friend were walking in the middle of West 18th Street when the two officers approached. At the time, they were working off duty and in uniform for SPAR (Springfield Preservation and Revitalization) Council. They later said they planned to ticket the men for walking in the street. But that’s not what happened.

After Battle’s friend was placed in a squad car, the officers said Battle became noncompliant. According to an article at the time in the Florida Times-Union, Battle “appeared to be hiding something, argued with Nobles, and pulled away. Nobles fired his Taser at Battle, and a gun dropped from [Battle’s] waistband as he collapsed.”

The officers said Battle then grabbed the gun, pointed it, and ran. Both officers fired. Battle was hit nine times with bullets from both officers’ guns.

The fatal incident constituted Nobles’ second and third officer involved shooting, according to media reports at the time, possibly because two suspects were involved. (JSO said it does not keep a list of shootings by officer.)

His first shooting occurred in Springfield in February 2008, when Nobles approached three men he thought were dealing drugs, then shot and wounded one he said had pointed a gun and fled, according to reports in the Florida Times-Union.

Nobles’ fourth shooting was in March 2015, when he fatally shot 16-year-old Kendre Alston. According to police, the teen pointed a loaded gun at Nobles during a car and foot chase. Though Alston dropped the gun during that pursuit, Nobles told investigators he didn't realize that. He shot Alston twice, once in the back of the head, according to a State Attorney’s Office review of the shooting.

Nobles’ fifth shooting occurred in April 2020 when he responded to calls for backup. A mentally ill woman, Leah Baker, 29, had stabbed an officer responding to a 911 call. Nobles was the first to respond to the officer’s frantic call for help and fatally shot Baker as she continued to lunge for a butcher knife, body cam shows.

Of all of Nobles’ shootings, this last one was “clearly good,” according to a JSO officer speaking on the condition of anonymity. Given that Nobles has had so many shootings, the circumstances of the Baker shooting “was a relief,” the officer said.

Nobles has supporters. On a community discussion blog shortly after he was cleared for the Kiko Battle shooting, one wrote, “Officer Nobles is a hell of a good guy and a good police officer. I’m sorry for the family’s loss but I’m also glad that we still have Officer Nobles on the streets.”

Another wrote, “I had coffee with Officer Nobles a few months ago, where he recounted some crazy stories of Springfield back when it was the Wild West. Good to see he's been formally cleared.”

Many officers also support him. One called him a “cop’s cop” – appreciated for being a hard worker and serious about crime fighting. One law enforcement source said Nobles is respected for taking off-duty patrol gigs and unlike some, doesn’t just “sit on his phone the whole time. He actually gets out of his car and works.”

“He’s definitely not lazy,” the officer said.

Rap videos and death threats There are two sides to every story

Melinda Patterson has a ground floor office on Arlington Expressway and a commensurate level of client contact. She represents people accused of drug possession, traffic crimes, weapons violations and grand theft – and though she’s been in practice just a little over six years, she’s dealt with hundreds of clients and law enforcement officials.

She says the name Nobles is well known in the community, particularly among young black men.

“Community-wise, this has been known for years, that Nobles was problematic, and he was not an upstanding officer with JSO,” she continued. “If you ask them about Nobles specifically, they have a story -- they have five stories -- about how they've dealt with Nobles. And that's how he's viewed in the entire community here.”

Biko Misabiko agrees Nobles he is a uniquely problematic officer. In 2016, Misabiko posted a picture of Nobles in his squad car on his Facebook page. “He listed his other officer-involved shootings and noted his prior testimony had been deemed “not credible after he changed his story.”

Two days later he posted again, saying his post prompted a visit from JSO.

“Yes, some special investigation officers popped up at my house the next day,” he recalled recently. “A detective asked me ‘did I have a problem with Officer Nobles?’ I said, ‘Yes, I do have a problem with him, because the way he treats people in our community.’”

Misabiko even created an online petition with more than 5,000 signatures seeking to have him removed.

Not all community reactions have been as tempered. Nobles has been on the receiving end of death threats. Patterson questioned him about it during a 2018 deposition in a RICO case brought against 10 alleged gang members. Nobles testified that one defendant, Danny Hadden, recognized his name from the Kendre Alston killing.

“He pretty much said that, instead of running, he wished he would have come out of the car with the gun,” Nobles testified. “If he ‘knew it was Sergeant Nobles,’ he would have come out of the car with the gun, and he would have tried to kill me.”

Patterson asked if Nobles was aware some gang members “tried to put a hit out on you, specifically, from inside the jail?” Nobles said he wasn’t. But he was aware of videos by Jacksonville rap artist and gang member Foolio focusing on the Kendre Alston killing.

It’s a particular concern in communities of color, plagued by unsolved violent crimes and often reluctant to engage with law enforcement. “JSO always says, ‘OK, we need better trust with the community,’” said Misabiko. “So you want the community to talk about the violence that's going on in the community -- but do you want also the community talk about the bad cops out on the street? And if you do, then you need to listen. Because it works both ways.”

Zona dismisses concerns about Nobles’ tough policing. “He spent his entire career in what we would consider high-crime areas, or busy areas of Jacksonville. And he's not a police officer that comes to work and just answers calls. …He comes to work every day, and he goes out there and he patrols the streets of Jacksonville looking for the bad guys. The ones with guns, the ones that are preying on the innocent people in our city, and he takes him off the street. Is he going to be involved in incidents like this? Are things like this going to come up? Absolutely. But he's a hard-working police officer. He's an honest police officer.”

Nobles has ardent community supporters, too. David Poland, who owns a coin laundromat at 38th and Main, said Nobles is unique among officers of rank in terms of involvement and interaction with the community. When Nobles worked in Zone 1, Poland said, he would frequently stop by to check in, and even chat with his customers. “He genuinely wants to hear and listen to what they have to say.”

“No other sergeant has ever come in said hello,” Poland said. “No lieutenant has ever come by either.”

Nobles’ style is evocative of “what officers used to do” Poland said, adding, “To me he seems like everything about him seems really nice and honorable.”

Attorney Tom Bell says effective policing is sometimes about style as much as substance. “If the community is going to trust law enforcement, they've got to be able to rely on honest police officers interacting with them in a respectful manner.”

That said, he thinks Nobles is a unique case, and believes the persistent questions about his credibility should prompt a re-examination of his work.

“I would hope there'd be some review,” he said. “I mean, because there's been a finding in one instance that he wasn't credible, does that mean that every other case is suspect? I don't know. But it would be certainly something that I would think should be reviewed.”

Patterson echoes that. “If Sergeant Nobles was the only basis of probable cause for a case, I definitely think it should be reopened.”

Leh Hutton wouldn’t address the issue of Nobles directly. “I’m really not going to discuss specific individual officers. I'm not sure that would be appropriate. But we will make an individual determination on every case, based on whatever evidence we have, what information we have as to how to proceed forward.”

Rosati thinks there is already ample reason to give Nobles’ cases a second look – including those that ended in prison time for a defendant.

“Police officers that put their lives on the line, they want to serve and protect, you know, 99.59% probably do that,” Rosati said. “But there's bad apples in every profession. And unfortunately, you know, one bad apple can destroy someone's life can destroy someone's family, their future. And, and it's all about credibility.”

[1] A recent legal interpretation of Marsy’s Law defines officers as “victims” in police shootings, so their names are redacted from reports. Nobles’ shootings were calculated using news reports and available records, as well as the recollections of JSO officers interviewed for this story.

[2] Hardin was fired by JSO in 2021 for illegally accessing police databases. She declined a request for comment.