The Donald Smith story isn’t about a system that failed.

It’s about a system that failed

and failed

and failed.

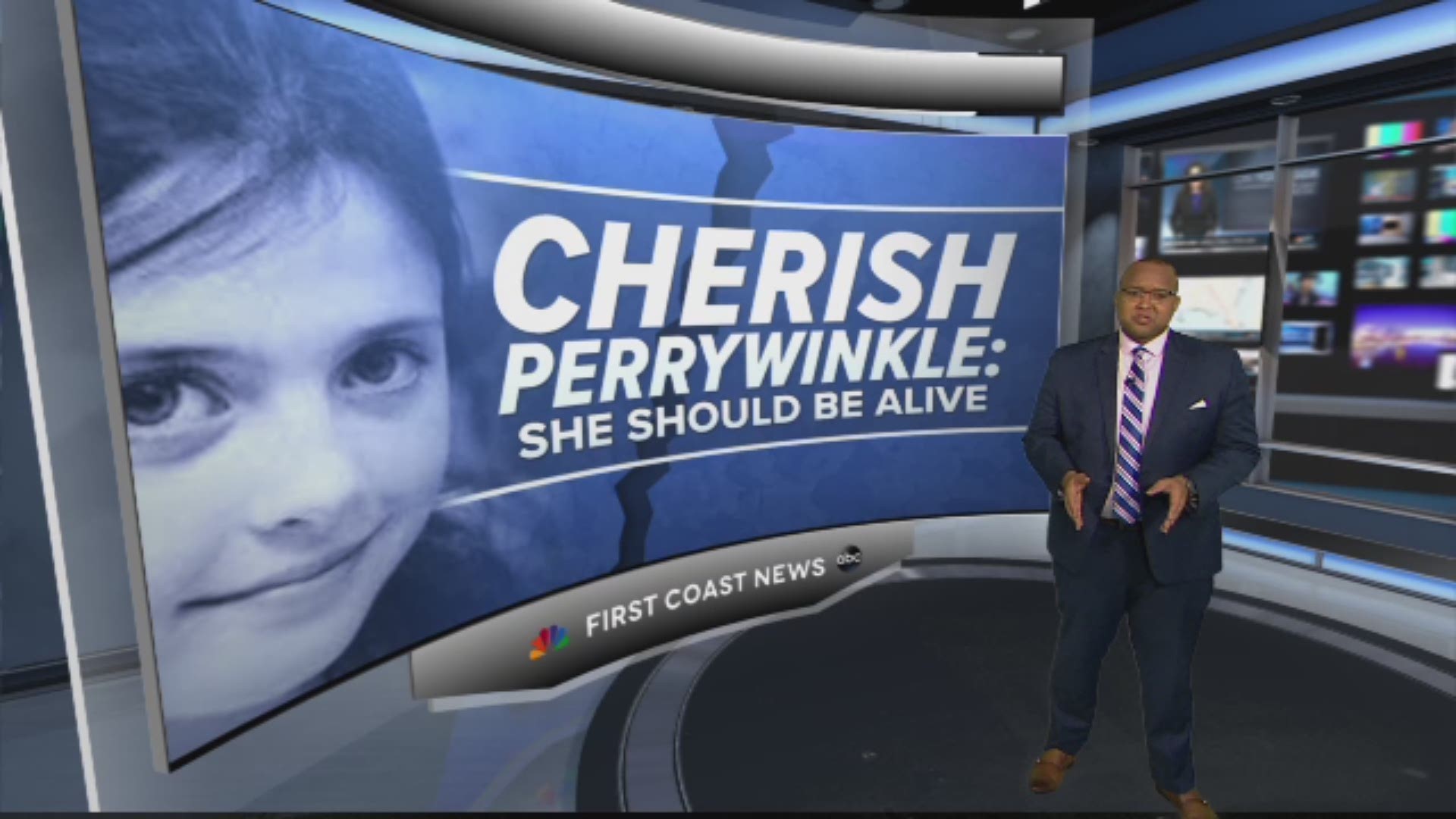

It ended with a dead 8-year-old – raped and strangled, her body dumped in a tidal marsh.

Donald Smith killed Cherish Perrywinkle just 20 days after he was released from jail in 2013. But the timeline between release and re-offense isn’t the most shocking in this case. That honor belongs to the 35 years that followed Smith’s initial designation as a sexually violent predator, in 1977.

In the intervening years, Smith snaked in and out of the criminal justice system, but never for long -- and not for the most serious charges.

Whether punished for petty crimes or sinister ones, the pattern was the same: Plea deals. Lucky breaks. Mistakes.

“Hindsight,” they say.

Everyone involved in this case says it, at some point.

****

Cherish Perrywinkle wasn’t even born when Donald Smith was first classified as a mentally disordered sex offender.

The girl’s mother was a child herself when, in 1977, Smith was arrested for lewd and lascivious exhibition after he masturbated in front of two girls who lived down the street from him.

“Do you want some of this?” he asked the girls, ages 5 and 8, according to the police report. “It’s my dick.”

It was Smith’s first sex offense, but the danger he posed was already clear. Circuit Judge Dorothy Pate determined he was “likely to commit further offenses” if released, and two psychologists labeled him a mentally disordered sex offender.

Smith was involuntarily committed to a treatment program in Gainesville. Doctors there found Smith unmotivated. He skipped therapy and broke rules. He was even caught with a homemade weapon.

Citing his “lack of progress,” doctors decided to release him.

“Smith has demonstrated little motivation to change his sexually deviant and generally antisocial behaviors,” doctors wrote. They added, without apparent irony, “It is the consensus of staff that Mr. Smith has received the maximum benefit possible from this program.”

The likelihood that Smith would “again engage in sexually deviant behavior” after release, they observed, was “highly probable.”

In September 1980, he was released.

****

For the next decade, Smith cycled in and out of jail and prison. Mostly for smaller crimes – worthless checks, battery, theft, even a jail escape attempt. Some crimes were serious enough to trigger felony charges, but most sentences were measured in months, whittled down by plea deals.

For instance, a grand theft and burglary charge in 1991 that could have landed him in prison for 20 years was negotiated down to just four months.

But Smith’s criminal evolution showed a sinister trend.

In June 1992 – the day after his son Donny Jr. was born -- Smith was arrested for prowling. Police caught him behind a woman’s house, crouched behind a doghouse inside a fenced yard. He was sentenced to a day in jail.

Four months later, things got much worse.

*****

“You don’t forget something like that. That’s a face I’ll never forget.”

Kerri-Anne Buck was Smith’s victim in 1992.

Just 13, she was walking in her Southside neighborhood when Smith drove up in his van. He asked if she knew “Susie,” and whether she wanted a ride.

“What did you say?” Assistant State Attorney Mark Caliel asked Buck, when she testified at Smith’s death penalty trail in 2018.

“I told him no.”

“What happened after you told him no?”

“He demanded that I get in the van.”

“Describe how he demanded that you get in the van.”

“He told me to get the f*ck in the van.”

Sobbing and trembling, Buck recalled how Smith, in broad daylight, chased her to a playground where she hid in the tunnel of a slide. “I was slipping, I was so afraid I was going to fall out, and he was going to find me.”

Buck’s testimony came a full 25 years after Smith tried to kidnap her, but the fear of her real-life boogeyman was palpable. Initially, she didn’t want to testify. She decided to, she said, to be a voice for Cherish.

“I’m the closest voice to the fear that Cherish felt,” she told First Coast News hours after her testimony. “I know how scared she must have been. I’m lucky to be alive today. She wasn’t that lucky.”

Hours after Smith chased Buck, he drove up to two other girls, ages 13 and 14. “Do you know Susie?” he asked. The girls demurred. He pulled out a picture of a woman performing oral sex on a man. “This is Susie,” he told them. The girls ran.

Smith was initially sentenced to 15 years, but his lawyer challenged the sentence and he was resentenced to 10. Smith appealed, saying his attorney had given him bad legal advice, and his sentence was reduced to 6 years.

In October 1997, he was released.

READ MORE >> The ones who got away: Donald Smith's other two child victims speak to First Coast News

*****

In January 1998, Smith was back in trouble.

In court records, it’s characterized a misdemeanor traffic offense – but the police narrative reveals something darker.

In response to a complaint of lewd and lascivious conduct, police found Smith inside his 1993 Pontiac Pro Am in the parking lot of an Albertson’s grocery store. He was bare-chested, pants open, with what appeared to be semen on his chest and KY Jelly coating his hands. There was an open bottle of vodka on the front seat, along with a two-liter bottle of warm urine.

After searching the car, police find drawings of penises and handwritten notes. One read, “If you want someone with a big dick, call me.” The other: “I want to see you hang by your neck.”

Smith was arrested, but there's no indication that formal charges were filed. Two months later, in March 1998, he was arrested for buying crack. That triggered a parole violation in the 1992 kidnapping case, and he was sent back to prison.

It would become one of the most consequential missed opportunities in Smith’s history.

On March 9, 1999, as he’s scheduled to be released, the Florida Department of Corrections sent an “urgent” fax to the Department of Children and Families, noting Smith was slated for “immediate” release. DCF, which oversees the state’s sexually violent predator program, sent two psychologists to evaluate Smith. They agreed he was dangerous.

In the months between Smith’s incarceration and his release, a new law had taken effect. The Jimmy Ryce Act, named for a child raped and murdered by a known sex offender, allowed for sexually violent predators to be held indefinitely if they were considered a threat to society.

Both DCF doctors concluded Smith met the criteria of the new law, and the State Attorney’s Office in Jacksonville filed a petition to have him permanently confined.

A public defender was appointed -- Ann Finnell, an attorney with a fearsome reputation. Some 185 docket entries followed, many of them motions filed by Finnell. She challenged the legality of involuntary detention, the reliability of psychological determinations of future dangerousness, the Jimmy Ryce statute itself.

The case stretched on for three years. And then, abruptly, prosecutors dropped it.

On April 17, 2002, Smith was released.

****

Ernst Bell was the Assistant State Attorney who made that decision. In his formal rationale, called a Disposition Statement, Bell explains it would've been a tough case to win. Case law has at that point established that Antisocial Personality Disorder and Exhibitionism, Smith’s two diagnosed mental illness, aren't sufficient to permanently confine someone.

Locating Smith’s attempted kidnapping victim, Kerri Anne Buck, would have helped the case, since she was the “only witness” to the kidnapping attempt, but Bell wrote, she “cannot currently be located, her whereabouts are unknown.”

(Contacted for this story, Buck says the state’s only effort to find her consisted of a business card left on her sister’s door. Bell didn’t specifically recall what efforts were made, but said that investigators were typically “diligent” in search efforts.)

In his Disposition Statement, Bell conceded that Smith “clearly has a drug problem and ... a penchant for public masturbation,” but reasoned there was no violence, or even physical contact, in his history.

Bell left the State Attorney’s Office a few years later, and now works as a corporate lawyer. His recollection of the case is fuzzy, but he “definitely remember[s]” Smith. “When he got arrested, I was like, crap. .. I told my wife, 'oh my God, I remember that guy. That was a case I handled back in the day.'”

Though Bell didn’t recall specifics of the case, after reviewing his Disposition Statement, he said he found his 2002 reasoning persuasive. He notes the Jimmy Ryce law was new; Donald Smith was one of the first Jacksonville cases. A U.S. Supreme Court case limited what constituted a qualifying mental illness. Not being able to locate the victim mattered.

“You can always Monday Morning Quarterback something,” Bell told First Coast News. “But as a prosecutor, you have an ethical duty not to bring cases, or only ones you can prove beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The case wasn’t dropped outright. Smith agreed to a “compliance plan” that included hormone shots, also known as chemical castration, and sex offender therapy. If he didn’t comply, the state warned, it could re-ignite Jimmy Ryce proceedings.

Thirty-five days later, Smith was out of compliance – and on the street.

****

Years later, State Attorney Melissa Nelson scribbled furious comments in the margins of the Disposition Statement. The annotated document, obtained by First Coast News, offers a revealing look at how prosecutors in the Cherish Perrywinkle case felt about that 2002 decision.

“Terrible,” Nelson wrote. “Seriously??” “What about THE VICTIM?” and, “TRY!”

Nelson acknowledges she wrote the comments, but says she did so in frustration.

“I know it’s my handwriting. I don’t remember when I did it or why I did it. I don’t have a good answer for that. I was really infuriated looking at the timeline and what I perceived as missed opportunities. It’s me yelling out loud to myself.”

Attorney Michael Bossen, who reviewed Smith’s case history for his 2018 trial, didn't know who made the comments, but said the annotations simply highlight questions others have raised.

“Why the prosecutor chose at the time not to just peruse it through the jury, and let the jury decide,” he said. “I don’t have an answer for that. That’s a great question.”

Nelson’s marginalia isn’t the only evidence that Bell’s 2002 Disposition Statement was flawed. In May 2002, a month after Smith’s release, his psychologist wrote a dire warning letter. Saying he wanted “to express my grave concerns,” Dr. James Vallely explained that Smith had quit therapy and was refusing chemical castration shots.

“This situation is terribly troublesome and dangerous,” Vallely wrote. He said Smith posed “a clear present and future danger to children and the community.”

Bell doesn’t recall getting Dr. Vallely's letter, or what he did when he got it. “That was a long time ago.” But he says Smith’s case posed unique challenges.

“That’s probably the first time we tried to retain some community control” over someone released after a confinement attempt. “It was most likely the first one of these where we tried to negotiate some community control.”

When Smith refused to cooperate, however, the agreement lacked teeth. Smith remained free. And despite subsequent arrests, the state didn't resurrect their Jimmy Ryce petition.

“I am not sure as far as the enforcement mechanism,” Bell says.

Contacted by First Coast News, Vallely said he never heard back from the State Attorney’s Office.

Two years later, an arrest for dealing in stolen property could have sent Smith to prison for 30 years. Instead, in 2004 -- the same year Cherish Perrywinkle is born on Christmas Eve -- he’s sentenced to two.

****

Heather Holmes is a forensic psychologist hired by Smith’s legal team to assist at his death penalty trial.

She calls Smith “exquisitely dangerous.”

“He is probably one of the most dangerous sexual offenders I have ever met,” she testified.

That’s why she found the 2006 conclusion of Smith’s evaluating psychologist so perplexing.

On the eve of his release, officials from the state Department of Children and Families reach out to the State Attorney’s Office. “He’s coming for renewal again,” one email warns. Clearly perplexed about the 2002 decision to drop confinement proceedings, an email asks to know -- “if it’s knowable” -- why he was released.

Because of his history, Smith’s release triggers a psychiatric evaluation. And this one -- despite his history, prior evaluations and the consensus view of nearly everyone who’s dealt with him -- says he doesn't meet criteria for permanent confinement.

“I wondered if it was a typo,” Holmes testified. “Because if this person, with these characteristics, who has been described as dangerous as a pedophile ….is ‘not meeting criteria as a sexual predator’ -- I don’t know who would be.”

(First Coast News was unable to reach Smith's psychologist, Dr. Chris Robison, for comment.)

“I don’t want to slam a colleague,” Holmes added. “I wasn’t doing the evaluation. But based on what I was reading, I was completely befuddled.”

“Obviously hindsight” she added. “20/20.”

In March 2007, Smith was released.

*****

Smith’s next arrest involved his own child, not a stranger’s. He was charged with child neglect, after he took his son to a crack house and refused to drive him home. According to the police narrative, the child “walked the streets of the northside of Jacksonville for several dark hours before he found Fire Station #18 and called police.

The charges were later dropped.

****

“He asked me if I wore a bra. I said, ‘No, but I do got some.’ He asked if I have hair on my private, and I said ‘no.’”

Chrystina Hand was 10 when Smith called pretending to be a child abuse investigator. He wanted to examine her, he said, to see if she’d been sexually assaulted by a relative.

Now 19, Hand remembers her grandma driving her to a Callahan McDonald’s to meet Smith for a sexual assault ‘exam’. Luckily her mom intervened and called police.

“They ended up going out that night and finding him, and they busted his nose, I can remember that," Hand told First Coast News.

Smith could have gotten 30 years if the case had gone to trial. But Hand’s mother was reluctant to make her daughter testify against her tormentor, and prosecutors made a deal. After two years in jail, on May 31, 2013, Smith was released

****

Three weeks later, a final missed opportunity.

On June 21, 2013 -- the night Cherish Perrywinkle was kidnapped and killed – police initially dismissed the child abduction as a custody dispute, or something nefarious involving her mom.

“I believe if they would have acted faster they would have found Cherish in ample time,” Cherish’s mother Rayne Perrywinkle tells First Coast News.

A police report lists 8 reasons police were skeptical of Rayne's story including “A total lack of tears when she appears to be crying,” and “repeated comments that she thought her daughter had been raped and murdered with an absence of emotional response.”

According to Rayne Perrywinkle, at least one officer intimated he thought she’d killed her daughter.

“Detective Cullen looked at me and said, 'You did it, I know you did it, and you’re going to prison,'” she told First Coast News. (Asked for comment, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office said, “We would encourage Ms. Perrywinkle to contact us to relay details of her complaint against Detective Cullen or any other JSO employee with whom she interacted.”)

It’s not clear exactly when the girl was killed. Her body was found 12 hours after the abduction, but the Medical Examiner wasn’t able to pinpoint a time of death. In secret jailhouse recordings obtained by First Coast News, Smith told his mom he crossed “the point of no return” before he even left the Walmart parking lot.

But there is no question that, at least at first, Rayne’s behavior was considered suspect. And doubt spelled delay – it would be three hours before the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office began the Amber Alert process, and another two – 5:28 am -- before the alert was issued.

That lag time was the subject of an internal investigation and officer discipline in the months that followed. Then-Undersheriff Dwain Senterfitt acknowledged it was a concern. “Do I think we would have found her in time to save her? Probably not. But if that was your 8-year-old little girl, would you want us to try?”

The story’s end was tragic, and tragically unsurprising. Everything anyone needed to know about Donald Smith was clear in 1977. “It’s been present for the last 40 years,” Dr. Holmes testified. “Reading through the records, I found it not only sad, but shocking.”

Michael Bossen agrees. “There were definitely ‘tells’ throughout the course of his conduct that this guy was a pretty seriously sick individual.” He adds, “He’s the definition of a sexual predator. Go to the dictionary, look up sexual predator: Donald Smith’s picture is going to be right there.”