As the dueling crises of a deadly pandemic and police brutality spark fear and anger in residents across Jacksonville, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office has done little to help the public understand its inner workings.

The Sheriff’s Office has never released body-camera footage of an officer shooting, even as officers have shot 12 people, killing seven, since every patrol officer was outfitted with a body camera by last December.

The Sheriff’s Office refuses to publish the number of people housed in its jails, and it won’t even list everyone sitting in the jail.

Despite requests, the Sheriff’s Office hasn’t released data on civilian shootings either, only sometimes informing the public when a shooting occurs, even as the city grapples with the most homicides of the first five months of any year going back more than a decade.

This week, the office quietly uploaded two videos of use-of-force hearings from a year ago. The hearings, which determine if an officer violated policy by using excessive force, used to be open to the public, but a court order, spurred from the police union’s lawsuit, closed them. During his campaign for sheriff, Mike Williams promised to re-open the hearings, but he has failed to do so.

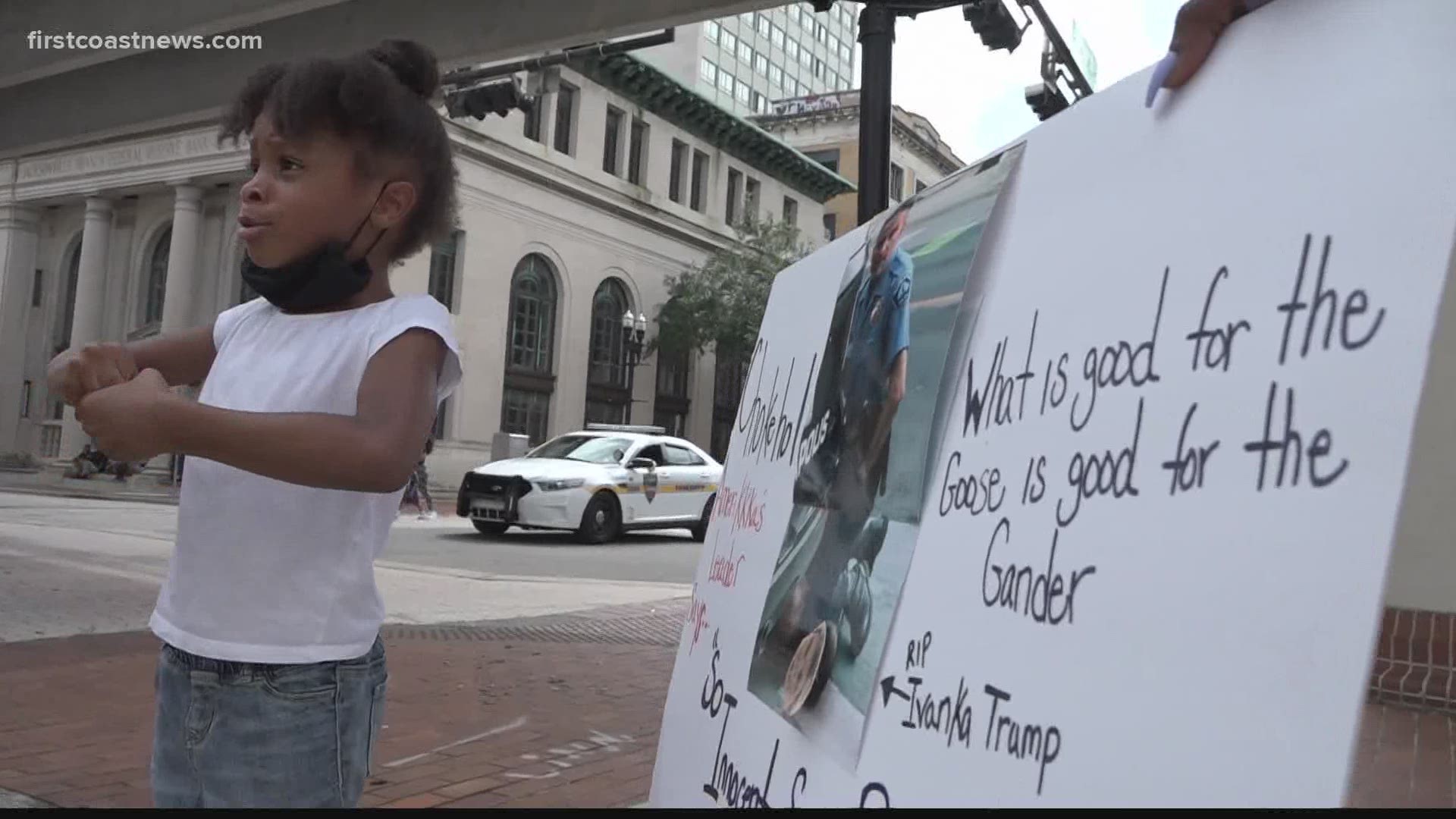

The anger at Jacksonville law enforcement’s lack of transparency has been building for years, and in the wake of police shootings of black people across the country, that anger has spilled out onto the streets.

Two weeks ago, on the steps of the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office headquarters, thousands of protesters packed in, some weeping and desperate. They recited the names of those dead at the hands of police. Jamee Johnson, Reginald Boston, Kwame Jones. With the names, the protesters sounded a demand, a demand they’d repeat in the protests that have followed: Release the footage.

In the last two weeks, Sheriff Williams, Mayor Lenny Curry and State Attorney Melissa Nelson have thanked protesters for keeping the peace and have said they’re aware of the issues roiling the city and nation, and they’re aware action is necessary.

While Williams and Nelson said they know the body-camera policy needs to change, none of the city’s leaders have announced actual policy changes.

On at least two other demands, city leaders have made moves. Curry acquiesced to demands that Confederate monuments come down, while Nelson has dropped charges in at least some of the about 80 arrests made the first weekend of protests

Nelson’s office dropped the charges in 48 arrests from two Sundays ago, saying prosecutors reviewed the footage and the law and “based upon the law, the facts, and the circumstances involved, this office declines to file charges.” A spokesman said the office was still reviewing other arrests made that weekend.

Curry made news when he decided to lead his own march with celebrity Jaguars running back Leonard Fournette and rapper Lil Duval. At the march, he announced he had “evolved” on the issue of Confederate monuments, ordering three monuments and eight historic markers be taken down.

Still, Curry was unwilling to commit to any specific reforms, instead saying he would wait “until voices are heard” in a committee setting. He said that “all discussions are on the table,” but later added that, “I’m going to keep giving law enforcement what they need.”

He said he would propose a City Council bill to create a committee to study the issue of racial justice. But he isn’t going to propose the bill until July, and he said he wouldn’t talk about reforms until the committee meets.

Curry, who oversees the Sheriff’s Office’s budget, which makes up 36 percent of the city’s general spending, said he will continue giving law enforcement what they say they need.

Nelson in a memo released Tuesday said there are “opportunities that exist for improvement” in the office’s policy on body-camera footage, though those policy changes have yet to come.

Williams said that he believes the Sheriff’s Office and the State Attorney’s Office need to find a way to promise to release body-camera footage by a certain time. “Let’s tell people how long that’s going to take. Give a promise to the community and don’t break the promise. We’ve come across legal hurdles and labor-law challenges.” He said that the mayor is responsible for bargaining those labor challenges with the Fraternal Order of Police.

Williams and Nelson both said they would come up with a plan to ensure footage is released by a certain date, something policing experts say would be a better policy. Both of their offices have said they worry releasing footage too soon could taint investigations.

On an Action News/WOKV discussion, Williams said those policies were going to come even if there were no protests.

During Williams’ five years in office, he has created a transparency website that lists most officer shootings, homicides and some office policies, including the office’s use-of-force policy. However, some in the community say it isn’t enough.

“It needs to be faster,” activist and teacher Christina Kittle told Williams, “and it needs to be more of a priority.”

WANTING MORE INFORMATION

Yvonno Kemp called the protests “a manifestation of our prayers.”

Her son, Reginald Boston, was shot and killed by police this year. Like the mothers of others in her boat, she’s been unable to find out information about her son’s final moments.

“It’s not right that people don’t know. It’s not right that the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office has every single thing on hold. They have the autopsies on hold, the exams done at the scene on hold. We can’t get no information from January the 21st to June the 12th. We still don’t know nothing. It’s sad.”

She said she didn’t understand why police give more information immediately at crime scenes when officers aren’t the ones shooting. “How is it you guys can release that it was 50 rounds shot at that scene where the police wasn’t involved in, but you can’t tell us how many times my child was shot?

“Y’all release the footage from the man stabbing the police at the protest, but you can’t release the footage when our child died. Because it’s officer-involved, you don’t want to release it. But you have this man’s picture on every news channel because he did something to the police. But the police did something to my child and it doesn’t get released.

“I’m angry. I’m still upset. I’m still praying. I’m still pushing forward and I’m not stopping until I get answers about my son.

Unlike other law-enforcement agencies, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office investigates its own shootings through a special Integrity Unit. In Northeast Florida, FDLE has investigated sheriff’s deputies in St. Johns, Columbia, Clay, Flagler, Nassau, and Putnam counties. It also investigates police shootings at larger offices like the Miami-Dade Police Department.

Police never contacted Latoya Cash after an officer shot and killed her son, Kwame Jones. She had to drive down to that same police headquarters to get answers the January morning after her son’s death to find out. Since then, she said, despite her constant phone calls, she’s never heard from anyone in the office. She said she just wants to see the video of the shooting.

“Whether it’s the police officer’s fault or the victim’s fault, the answer’s right there. It would make life a lot easier.”

Cash and Kemp said it’s been inspiring to see protesters chanting their sons’ names, but it shouldn’t have taken this long to get answers.

LEGAL LOOPHOLES

The families of victims aren’t the only ones who’ve complained about the Sheriff’s Office’s lack of transparency recently.

In one case his office represents, a man was charged with six offenses related to an incident where he’s accused of having a mental-health breakdown and driving into a police car. After the police union complained about the man getting a bond of $15,768 when he “seriously injured” an officer, the State Attorney’s Office requested the bond be increased to $290,000. It turns out, the serious injury was that the officer broke his hand after punching the man in the face, according to the State Attorney’s Office. Cofer said as of last week, the footage still had not been released to the man’s lawyer.

And while the Sheriff’s Office has sent daily updates on the jail population to the State Attorney’s Office, it has not done the same with Cofer’s office.

The Florida Times-Union has also requested daily updates but has been denied those, even when submitted as records requests, and the office has been unwilling to post on its website how many people are currently sitting in jail.

Attorney Matt Kachergus said he wants the Sheriff’s Office to start reporting how many inmates have even been tested for COVID-19.

Some records come with significant delays.

In January, the newspaper requested the office’s database of all shootings, not just those involving police. The Times-Union paid more than $200, yet the office still hasn’t provided it.

Even the most basic of public records is elusive: a jail log. The Sheriff’s Office said a request for the jail log could cost thousands of dollars to redact because it would need to check if any inmates are the children of law-enforcement officers and therefore, according to the Sheriff’s Office, allowed to have their names exempted under state law.

That means when the child of a police officer or a current or former prosecutor commits a crime, the Sheriff’s Office could refuse to share the name of the accused.

“There’s a real misuse of that statute,” said Frank Lomonte, a media law professor at the University of Florida and director of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information.

The exemption is permissive, which means the office doesn’t have to exempt those names, but the Sheriff’s Office takes the stance that if it can come up with a legal reason not release something, then it will.

“That’s always the nightmare scenario when legislators start creating this special category in public records,” Lomonte said. “We are in a cultural moment now where the answer to the question of disclosure cannot be disclose the minimum that the law allows after dragging it out at the longest time at the greatest possible expense. That is not the right answer anymore.

“If it was ever something we could tolerate. We can’t tolerate it now. We’re facing two crises: COVID-19 and the killing of unarmed black people by police. Both converge on the reliable need for information so we can trust our government.

“If you’re in public service and your answer is I’m going to give you the least possible information after making you wait the longest possible time, then you should not be in government.”

The same exemption is true for body-camera footage.

Florida law has two distinct words to describe things that agencies don’t have to release to the public: confidential and exempt.

Confidential means an agency is not allowed to release something.

Exempt means an agency doesn’t have to release something.

While a criminal investigation is ongoing, certain evidence is exempt from release. But that doesn’t mean agencies can’t release it.

Yet while a police officer’s disciplinary review of a complaint is ongoing, the Florida Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights says the complaint and evidence is confidential for up to 45 days.

Regardless, there’s nothing under the law stopping the State Attorney’s Office from releasing the footage. During protests there, the Orlando Police Department has proactively posted footage from body cameras on its website this month.

And it’s not like law enforcement is shy of publicizing footage while an investigation is ongoing. During the protests, police said, someone was seen cutting an officer’s neck. The Sheriff’s Office repeatedly publicized footage of the person.

The Sheriff’s Office sometimes even proactively pushes footage out, like it did with body-camera footage of the traffic stop of a black city councilman. When the president of the police union asked the Sheriff’s Office to investigate whether the councilman had falsely reported his car as stolen, the office assigned its special investigations unit. The office then released body-camera footage of the incident, along with its investigative report, on its website.

Yet getting footage of arrests of protesters from that same office has been much more difficult, even when some of those protesters have claimed police brutality.

With the Sheriff’s Office taking so long to release body-camera footage to defense attorneys, a team of lawyers at different firms took action on their own, forming a committee that has been sharing evidence and intelligence with one another.

That’s how Belkis Plata found footage of one of her four clients, each of whom she’s representing pro bono, getting slammed to the ground two Sundays ago at the protests.

Summer Clements was seen walking on a sidewalk when an officer approaches her. She puts her hands on a wall, but the officer puts his arm around her neck, jerks her back and throws her to the ground. She was arrested for resisting and unlawful assembly and spent three days in jail before she could afford the $2,006 bond. The video only shows 31 seconds, so it’s not clear what happened before what’s seen on camera.

You wouldn’t have known that from her arrest report, which gave no details of her arrest.

It only said: “After the protest, due to concerns of public safety, at 13:45, announcements were made for all individuals to disperse the area and avenues of exodus were given. The suspect failed to disperse from the area as ordered.” It didn’t explain why she wasn’t arrested until three hours later, how she resisted or if she even heard the initial announcement.

It also never mentioned the body slam.

In fact, her arrest report looks like it could’ve been copied and pasted from the dozens of other arrest reports filed that day.

“Everyone is out there because they’re so angry with what’s happened with George Floyd and everyone else,” Plata said. “They simply want to be part of the movement to change things, and lo and behold they’re victimized themselves.”

The arrest was one of the 48 that State Attorney Nelson dropped.

When asked during the Tuesday march about use-of-force incidents with the mayor, Williams noted that the office’s transparency webpage includes links to PDFs of annual reports that include some information about the incidents.

But those annual reports differ from more detailed ones produced by the office’s crime-analysis unit. The detailed versions, which include 36 pages of analysis about how police use force, show that 56 percent of people who police used force on were black men, who make up 14 percent of the city’s population.

Police used force 553 times last year, and jail guards used force 322 times. Out of all of those incidents, police officers were injured 72 times, and guards were injured 14 times.

In 79 percent of cases, suspects were unarmed. Police found firearms on just seven percent of people who police used force on. Seventy-three percent of officers who used force were white men, compared to 10 percent who were black men. And seventy-three times police officers used force off-duty.

The most common weapon a suspect used was “hands / fist / feet / teeth / etc.”

Seventy-one percent of the time suspects were injured; 13 percent of the time, officers were injured.

One officer used force 11 times last year. Another used force 13 times.

The Times-Union filed a records request Friday to learn who those officers were.