JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — A seashell pressed to the ear makes a sound like the ocean. But for Dr. Harry Lee, each shell is a symphony.

“Various movements, various levels of relatedness to one another -- functionality, colors, shapes -- all come together in this great symphony of natural history.”

Seated in the basement of his home on the Ortega River the retired Jacksonville physician says he first heard the siren song as a 6-year-old. He describes himself as an acquisitive child – “you have to be if you’re a collector” – who coveted and admired the shell collection of his Grandma’s next-door neighbor in New Jersey.

“I think he knew that I was a collector,” Lee muses. “It didn’t take long -- and it was his fault.”

Over the next seven decades, Lee would amass the largest private shell collection in the world – a mix of seashells and snail shells comprising more than 35,000 specimen trays.

“On a scale of 1 to 10 it’s a 10,” he says. “I’ve been at it 72 years. I’ve had plenty of time to do it right.”

Lee collected shells in his Jacksonville basement, but they flowed from trade and travels around the world, from the coast of Kenya and Tanzania to Fiji, Tahiti and Hawaii.

Not all his shells are from exotic locations. One of his most prized discoveries he found in the dirt along a highway in Hastings. Just a quarter-inch across, the otherwise unremarkable snail shell whorled in the wrong direction -- an abnormally reversed coil.

“A dealer would say that’s not worth a dollar, but to me, that’s one in a hundred thousand and is a spectacular item,” Lee says. “No one else has one, so beauty is in the eye of the beholder. At least the value is.”

As for the actual value of his collection, it’s been reported to be worth at least a million dollars, though Lee declined to say. “It’s the kind of thing my wife doesn’t want to know,” he laughs.

Its value dropped a bit, unexpectedly, seven years ago. Following a month of rain in June 2012, his home’s crawlspace filled with water, and eventually burst, flooding the basement in just over an hour.

“It was diluvian,” Lee says. “It came up three feet. It was just unprecedented I didn’t know how to cope with it.”

He was able to clean and restore the collection with the help of volunteers from the University of Florida’s Natural History Museum -- which is also where, over the past several years, he has been gradually relocating his collection.

“It a life’s work and it’s pretty good I think,” he says. “And the museum is fairly happy to have it.”

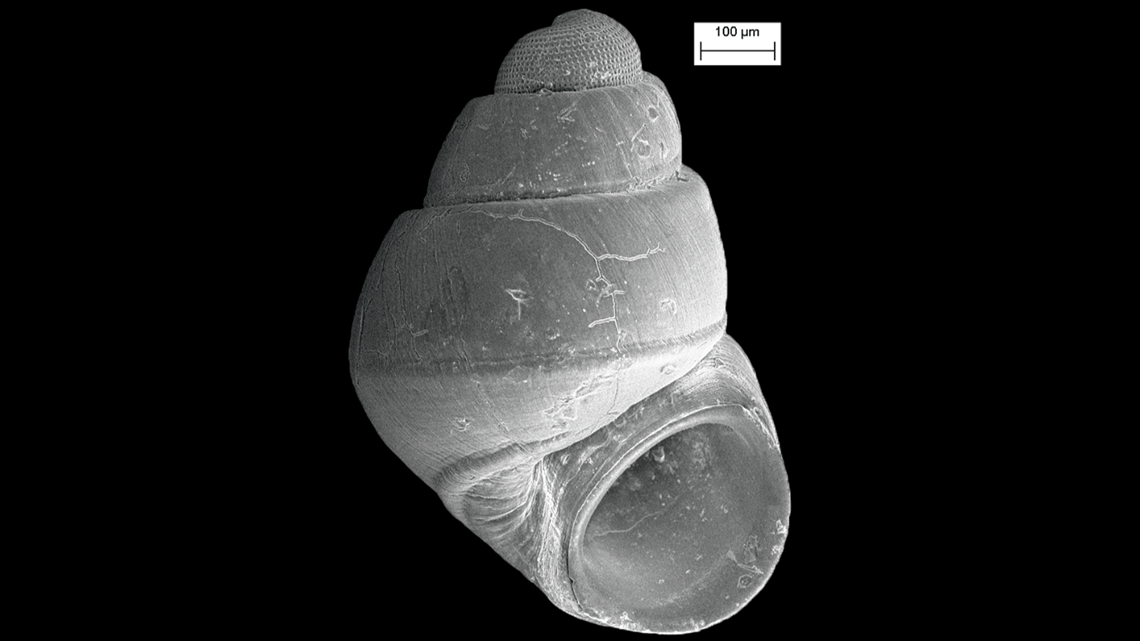

Lee is downsizing in other ways, now focused on shells so tiny, most people literally can’t see them. Using an electron microscope, he photographs microscopic fossil snails -- some 3 million years old, and only as wide as two strands of hair.

Lee’s impact on the world of mollusks isn’t just as a collector. He’s discovered them, including Dryachloa dauca a tiny orange snail he discovered in his own backyard. He wrote the definitive book on Northeast Florida seashells, “Marine Shells of Northeast Florida.

And he has 19 species of named for him, including the Ensis leei, also known as the Atlantic jackknife or razor clam -- one of the more common shells on Northeast Florida beaches.

“It’s an honor to have a shell named for you, but I’ve never asked that to be the case,” Lee says. “I had to be pretty old before I had the first one named,” he jokes. “I thought I’d have one named for me as a teenager. That’s not the way it worked.”

But while Lee’s impact on the world of shells continues, his days as a collector are over.

“Very few people can say this but I’m happy,” he said. “There are few very rare shells that I don’t have or didn’t have, but I don’t care that much anymore -- I’ve done all the damage I can.”